In 1892 she married Karl Kollwitz, a doctor who treated mainly working class patients, and moved with him to Berlin. Together they got involved in left-wing politics and also tried to help their poor neighbors; it was mainly through her husband's practice that she had contact with real working class people. This drawing is from a series of works illustrating a failed Silesian weavers' revolt of 1842, the subject of a popular play; this one is variously dated 1892 to 1897. Kollwitz sometimes did multiple different woodcuts or engravings based on the same drawing, so a lot of her stuff shows up in museum catalogs with contradictory dates.

Kollwitz once wrote,

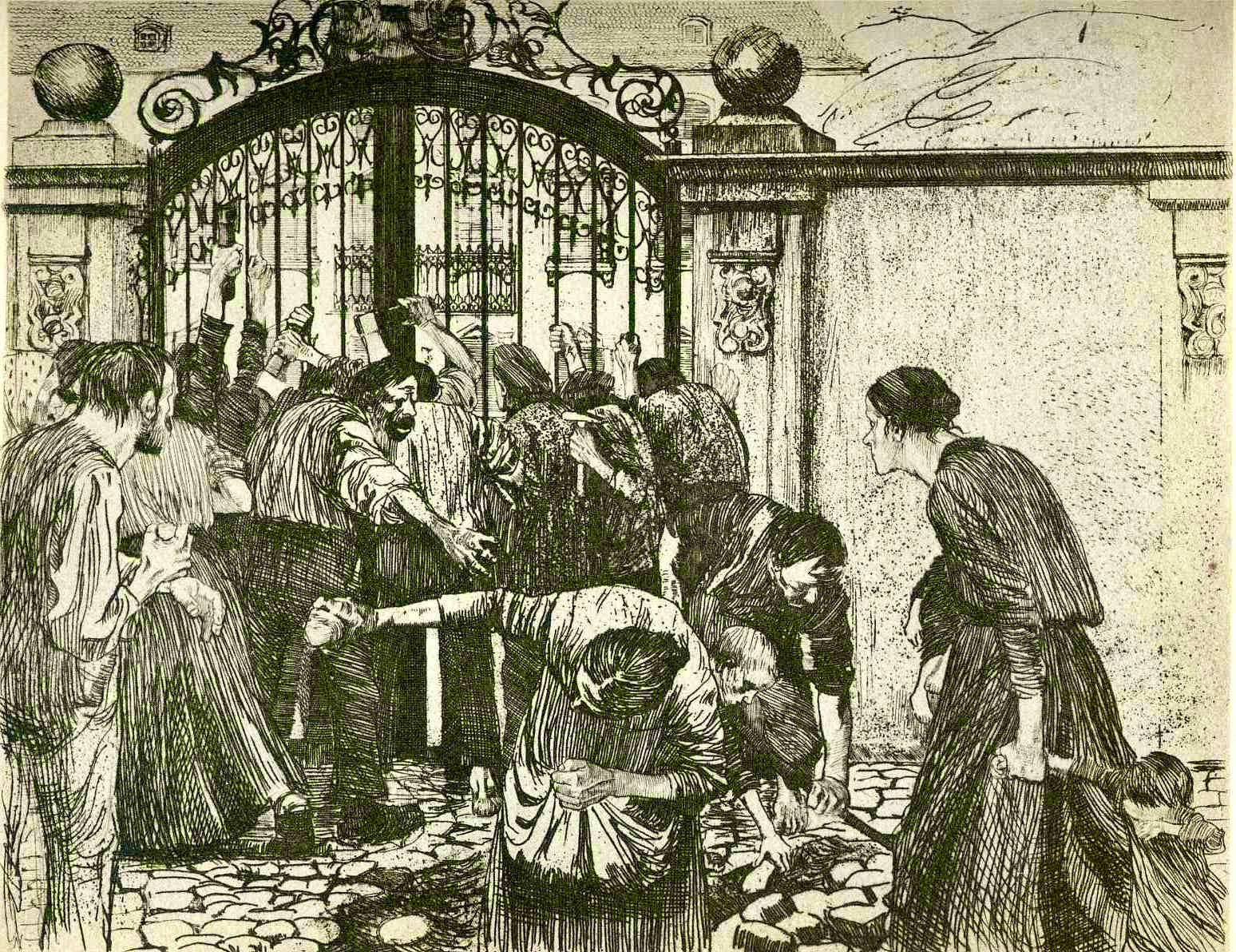

The motifs I was able to select from this milieu (the workers' lives) offered me, in a simple and forthright way, what I discovered to be beautiful.... People from the bourgeois sphere were altogether without appeal or interest. All middle-class life seemed pedantic to me. On the other hand, I felt the proletariat had guts. It was not until much later...when I got to know the women who would come to my husband for help, and incidentally also to me, that I was powerfully moved by the fate of the proletariat and everything connected with its way of life.... But what I would like to emphasize once more is that compassion and commiseration were at first of very little importance in attracting me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was simply that I found it beautiful.Outbreak, 1903. I like this a lot although I have no idea what it is supposed to depict. It seems somehow to connect a worker's uprising with deep events in the psyche, or in dreams.

The Battlefield, 1907.

Kollwitz seems always to have been a nervous mother; she drew grieving mothers more often than happy ones. This is Death, Woman, and Child, 1910. Kollwitz's horror of war and fear of death did not begin with World War I and her own personal losses, but seem to have sprung from her soul.

Mother with her Dead Child, 1903.

Then in 1914 the Kollwitz's youngest son Peter was killed in battle. This loss plunged Kollwitz into a depression that lasted for years. She designed and then destroyed at least two different memorials for her son before she finally completed one in 1932. As I said, she was already anti-war and very much worried about death, but as she returned to active artistic work in the 1920s the horror of war became her dominant theme. The Mothers, woodcut, 1921.

The Survivors, a lithograph of 1923. In the 1920s Kollwitz was honored by the Soviet revolutionaries and there were major exhibits of her work in Leningrad and Moscow; an exhibit of her prints was part of the celebration for the tenth anniversary of the revolution in 1927. But then Stalin turned against her as too sentimental and weak.

Self Portrait. Kollwitz was banned by the Nazis after they came to power, and her husband was forbidden to practice medicine. During World War II one of her grandsons was killed and her studio was destroyed by Allied bombs. She died on April 22, 1945, amidst the ruins of her homeland.

After the war (and her death) Kollwitz became a German icon, her art celebrated as the antithesis of Nazism. Here is her sculpture Mother with her Dead Son as displayed in the War Memorial in Berlin. Now there are two museums dedicated to her work in Germany, in Berlin and Cologne, and a Kollwitz prize given for artistic activism. I can think of no other artist whose work so purely expresses the axiom that the pain of life is the soul of art.

1 comment:

"Outbreak, 1903. I like this a lot although I have no idea what it is supposed to depict. It seems somehow to connect a worker's uprising with deep events in the psyche, or in dreams."

Perhaps it's just the workings of my own mind, but with the mass of rushing figures wielding polearms, one of the most common European weapons of all history, I immediately appended "of War" to the title of this piece.

Post a Comment