Wednesday, January 31, 2018

Tuesday, January 30, 2018

Immigration, Dynamism, and the Sort of Country We Want to Be

David Brooks has put all his talents to work in crafting the strongest possible case for immigration. He has, he says, tried several times to write a moderate essay on immigration, because it is his general belief that in any major political dispute there is something to be said for both sides. But in the case of immigration he has been unable to do it:

What Brooks misses is that not everybody wants to live in a fast-paced, fast-changing country. Some people mainly want things to be the way they always have, even at the price of being poorer and having less cool stuff. Some people think it's great that we move less than we used to, because they think being home with your family and the other people you grew up with is much better than going to the city and getting rich among strangers. Some people think not changing jobs is also great, and mourn for the days when men could work all their lives in the same factories where their fathers worked. Some people don't want to work twelve hours a day and scrimp and save like immigrant shopkeepers, but want ease and comfort. They think that all the hard-working immigrants are just bidding down the price of labor, making it impossible to earn a decent living at a regular old job. And they suspect that the surge of immigrants and the troubles of the white working class are related, maybe even two sides of the same coin.

Me, I'm on the side of dynamism. I have a miserable daily commute down to Washington, but I have never tried to get out of it. I get a charge of coming down into the Metropolis where a hundred kinds of people are doing a thousand different things, where the person you chat with in the line at an ethnic food truck might be a coder from Serbia or a truck driver from Somalia or a lawyer from Rochester. It feels exciting and alive, and we all have to work a little harder to share in that dynamism, that seems to me a price worth paying.

But I do understand that not everybody wants this, so I have never been able to feel any anger against immigration restrictionists. They want what they want, and it is what half or so of humanity has always wanted. There is nothing inherently evil or racist in wanting to stay home in a place that feels familiar. Brooks' argument does not even touch this whole side of politics, of life. He could write that moderate column if he would glance away form the economic statistics and ask himself instead what it is that people really want, and what really makes them happy.

That’s because when you wade into the evidence you find that the case for restricting immigration is pathetically weak. The only people who have less actual data on their side are the people who deny climate change.I consider this argument irrefutable. If what you want is a dynamic, exciting, economically thriving nation, you should support more immigration.

You don’t have to rely on pointy-headed academics. Get in your car. If you start in rural New England and drive down into Appalachia or across into the Upper Midwest you will be driving through county after county with few immigrants. These rural places are often 95 percent white. These places lack the diversity restrictionists say is straining the social fabric.

Are these counties marked by high social cohesion, economic dynamism, surging wages and healthy family values? No. Quite the opposite. They are often marked by economic stagnation, social isolation, family breakdown and high opioid addiction. Charles Murray wrote a whole book, Coming Apart, on the social breakdown among working-class whites, many of whom live in these low immigrant areas.

One of Murray’s points is that “the feasibility of the American project has historically been based on industriousness, honesty, marriage and religiosity.” It is a blunt fact of life that, these days, immigrants show more of these virtues than the native-born. It’s not genetic. The process of immigration demands and nurtures these virtues.

Over all, America is suffering from a loss of dynamism. New business formation is down. Interstate mobility is down. Americans switch jobs less frequently and more Americans go through the day without ever leaving the house.

But these trends are largely within the native population. Immigrants provide the antidote. They start new businesses at twice the rate of nonimmigrants. Roughly 70 percent of immigrants express confidence in the American dream, compared with only 50 percent of the native-born.

Immigrants have much more traditional views on family structure than the native-born and much lower rates of out-of-wedlock births. They commit much less crime than the native-born. Roughly 1.6 percent of immigrant males between 18 and 39 wind up incarcerated compared with 3.3 percent of the native-born.

What Brooks misses is that not everybody wants to live in a fast-paced, fast-changing country. Some people mainly want things to be the way they always have, even at the price of being poorer and having less cool stuff. Some people think it's great that we move less than we used to, because they think being home with your family and the other people you grew up with is much better than going to the city and getting rich among strangers. Some people think not changing jobs is also great, and mourn for the days when men could work all their lives in the same factories where their fathers worked. Some people don't want to work twelve hours a day and scrimp and save like immigrant shopkeepers, but want ease and comfort. They think that all the hard-working immigrants are just bidding down the price of labor, making it impossible to earn a decent living at a regular old job. And they suspect that the surge of immigrants and the troubles of the white working class are related, maybe even two sides of the same coin.

Me, I'm on the side of dynamism. I have a miserable daily commute down to Washington, but I have never tried to get out of it. I get a charge of coming down into the Metropolis where a hundred kinds of people are doing a thousand different things, where the person you chat with in the line at an ethnic food truck might be a coder from Serbia or a truck driver from Somalia or a lawyer from Rochester. It feels exciting and alive, and we all have to work a little harder to share in that dynamism, that seems to me a price worth paying.

But I do understand that not everybody wants this, so I have never been able to feel any anger against immigration restrictionists. They want what they want, and it is what half or so of humanity has always wanted. There is nothing inherently evil or racist in wanting to stay home in a place that feels familiar. Brooks' argument does not even touch this whole side of politics, of life. He could write that moderate column if he would glance away form the economic statistics and ask himself instead what it is that people really want, and what really makes them happy.

Monday, January 29, 2018

In New Mexico, the Descendants of Indian Slaves

Interesting story by Simon Romero in the Times about American Hispanics who discover slaves among their ancestors:

These slaves were treated in different ways. Some became household servants or field hands. But quite a few were settled in slave villages on the border of Spanish and Indian land, to serve as a buffer. The name Genízaros is thought to come from the Turkish word Janissary, which referred to slaves used as soldiers. Abiquiú, New Mexico is one of several towns that began as a community of Genízaros.

Because of the ethnic mixing that took place in Mexico, most Mexicans and American Hispanics have both Indians and Europeans among their ancestors. (One genealogist quoted in the story says his clients are typically 30 to 40 percent Indian.) Which means, given the extent of the Indian slave trade, that many Hispanics (and Mexicans) have both slaves and slave owners among their forebears.

And the detail that really brings the story up to date is that many of these people are now choosing to identify with the oppressed among their ancestors rather than the oppressors:

Lenny Trujillo made a startling discovery when he began researching his descent from one of New Mexico’s pioneering Hispanic families: One of his ancestors was a slave.These slaves were Indians. In the 17th century they were mostly captured and enslaved by the Spanish (and their African companions), but after 1700 most were enslaved by other Indians. The Comanche Empire in particular was a great slave raiding and slave trading state.

“I didn’t know about New Mexico’s slave trade, so I was just stunned,” said Mr. Trujillo, 66, a retired postal worker who lives in Los Angeles. “Then I discovered how slavery was a defining feature of my family’s history.”

Mr. Trujillo is one of many Latinos who are finding ancestral connections to a flourishing slave trade on the blood-soaked frontier now known as the American Southwest. Their captive forebears were Native Americans — slaves frequently known as Genízaros (pronounced heh-NEE-sah-ros) who were sold to Hispanic families when the region was under Spanish control from the 16th to 19th centuries. Many Indian slaves remained in bondage when Mexico and later the United States governed New Mexico.

These slaves were treated in different ways. Some became household servants or field hands. But quite a few were settled in slave villages on the border of Spanish and Indian land, to serve as a buffer. The name Genízaros is thought to come from the Turkish word Janissary, which referred to slaves used as soldiers. Abiquiú, New Mexico is one of several towns that began as a community of Genízaros.

Because of the ethnic mixing that took place in Mexico, most Mexicans and American Hispanics have both Indians and Europeans among their ancestors. (One genealogist quoted in the story says his clients are typically 30 to 40 percent Indian.) Which means, given the extent of the Indian slave trade, that many Hispanics (and Mexicans) have both slaves and slave owners among their forebears.

And the detail that really brings the story up to date is that many of these people are now choosing to identify with the oppressed among their ancestors rather than the oppressors:

A growing number of Latinos who have made such discoveries are embracing their indigenous backgrounds, challenging a long tradition in New Mexico in which families prize Spanish ancestry. Some are starting to identify as Genízaros. . . .Of course just having Indian ancestors doesn't make you an Indian under US law; you have to belong to an organized community with traditions tracing back to pre-conquest times for that. But that won't keep people from trying to claim that identity.

Pointing to their history, some descendants of Genízaros are coming together to argue that they deserve the same recognition as Native tribes in the United States. One such group in Colorado, the 200-member Genízaro Affiliated Nations, organizes annual dances to commemorate their heritage.

“It’s not about blood quantum or DNA testing for us, since those things can be inaccurate measuring sticks,” said David Atekpatzin Young, 62, the organization’s tribal chairman, who traces his ancestry to Apache and Pueblo peoples. “We know who we are, and what we want is sovereignty and our land back.”

Today's Sentence

From Kevin Williamson's essay on Steve Bannon's rise and fall:

Bannon himself flirted with Zen Buddhism before returning to his mother’s Catholicism, in which he is a Latin Mass traditionalist in principle but a thrice-divorced partisan of Mammon in practice.

Sunday, January 28, 2018

Tibetan Ornament, 18th-19th Century

Gold, silver and turquoise. From a Tumblr I just discovered, Jewels of the Ancient World.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Jordan Peterson, the Nietzschean, Jungian, Tough-Guy Guru for Our Time

Until this week, I had never heard of Jordan Peterson. And then suddenly he was everywhere: hero of the most watched video on Youtube, subject of a David Brooks column, proclaimed by Tyler Cowen to be the most important public intellectual in the world. Controversy swirls around him: various professors have accused him of mounting a dangerous threat to human rights, and a movement has sprung up to strip him of his tenure. Yet he has, people say, a huge following among young men, especially among troubled young men. As the father of two young men who have had their share of troubles, I wanted to find out who Jordan Peterson is, and what he says that so many young men find compelling and so many other people find deeply disturbing.

This is easy to do, because Youtube has dozens of videos of him talking. After spending much of last night and today watching him, I think I can speak to both why he is loved and why he is hated. If you want a five-minute exposure to Peterson, I suggest this clip in which he speaks about how to overcome social anxiety.

I think the most important point to make about Peterson is that he is a therapist. People keep trying to interpret him politically, but so far as I can tell he has little interest in politics. I have written here before about the great divide between the political and therapeutic approaches to the world, and confusion over the difference is corrupting how people react to Peterson. The world is hard, you know, and full of suffering. To this the politician says, "let's fix things so there is less suffering and less difficulty." The therapist says, "You have to become a tough enough person to endure the suffering and overcome the difficulty." Most of Peterson's controversial statements take the form of "stop complaining and toughen up." This enrages politically-minded people, who say, "You mean we shouldn't try to fight sexism and racism and lift up the poor?" Peterson rolls his eyes and says, "Go ahead and do what you can to improve the world, but meanwhile we all need to toughen up and get on with our lives." "So," say the activists, "you're saying that the suffering of the poor and the oppressed is their fault?" Round and round it goes, a perfect circle of misunderstanding.

The second thing about Peterson is that he is a Jungian in love with myths and archetypes. Like James Campbell or Robert Bly, he is always explaining contemporary things by reference to ancient Egypt or the pyramid on the dollar bill. This includes Jungian ideas about male and female; Peterson firmly believes that men and women are different in ways reflected in ancient stories. One of the best lectures of his I have seen riffs on the story of Peter Pan. The only example of adult masculinity he knows is the toxic one of Captain Hook, so he refuses to grow up, even though that means he can't have a real woman (Wendy) and has to make do with Tinkerbell, "the imaginary fairy of porn."

Like most modern Jungians Peterson draws on evolutionary psychology to buttress his views. He is always referring to dominance hierarchies, submissive gestures, reproductive success, the whole vocabulary of animal behavior. Thus you get passages like this one, from a long explanation of how life is poised between order and chaos:

Peterson is especially interested in the dark side of our personalities, for good Jungian reasons. Until we confront and incorporate the dark, destructive sides of our natures, we are incomplete. In another video I watched, but have lost the link to, Peterson says you don't want to be the person who can't be cruel. Those people are weak and easily bullied. You also don't want to be a cruel person. You want to be the person who can be cruel but then does not; who is not afraid of his murderous darkness but has drawn it forth and mastered it. Weakness is not virtue; only the strong can truly be virtuous. And Peterson likes to display his "strength," as here, when he questions a call to treat everyone with respect:

Peterson is a reactionary in some ways, especially about several key questions that are prominent on college campuses. He hates identity politics because his main focus is the therapist's preoccupation with the healthy individual. He hates the whole movement to treat gender as something to be de-emphasized or changed at will because he believes that the eternal masculine and feminine are fundamental to our souls. He hates whining about the 1 percent because he thinks it is envy. He hates post-modernism because he thinks it subordinates truth to politics, and he believes very firmly that certain things are true whether you like them or not.

Plus – and this is the thing that gets the most exclamation points from his Youtube-posting fans – he hates big parts of contemporary progressive discourse because he believes they are hurtful to the young men he is trying to treat:

When Peterson does talk about politics directly he is much less compelling than when he talks about myth or psychology. In this interview he takes student activists to task for trying to change systems they do not understand. Why, he asks, do students who can't even clean their dorm rooms think they know how to make the country better? It's a strange, managerial approach to politics, as if these things could be done without any ideology or any passion. It is probably true that student activists would make a complete hash of running the government, but without the passion of activists, would anything ever change? Peterson thinks about students from a psychological perspective, and he sees them acting out rebellions against their parents and finding their identity through joining the cool club and so on. All of which is important and true, but still leaves out something vital about political activism in our age.

But as I said, Peterson rarely talks directly about politics. And yet – and this is what fascinates me –he has ended up in a political storm anyway. Politics and psychology are, I suppose, different ways of looking at the same thing: how people live together. So a way of understanding psychology necessarily has some political implications, and vice versa. I don't think, though, that we understand at all how to make them work together. Right now we have politics that demand we act rationally and psychology that explains why we never do; does that make any sense? Can we imagine a political system that both promotes mental health and draws realistically on the strengths and weaknesses of our minds?

For now, no.

This is easy to do, because Youtube has dozens of videos of him talking. After spending much of last night and today watching him, I think I can speak to both why he is loved and why he is hated. If you want a five-minute exposure to Peterson, I suggest this clip in which he speaks about how to overcome social anxiety.

I think the most important point to make about Peterson is that he is a therapist. People keep trying to interpret him politically, but so far as I can tell he has little interest in politics. I have written here before about the great divide between the political and therapeutic approaches to the world, and confusion over the difference is corrupting how people react to Peterson. The world is hard, you know, and full of suffering. To this the politician says, "let's fix things so there is less suffering and less difficulty." The therapist says, "You have to become a tough enough person to endure the suffering and overcome the difficulty." Most of Peterson's controversial statements take the form of "stop complaining and toughen up." This enrages politically-minded people, who say, "You mean we shouldn't try to fight sexism and racism and lift up the poor?" Peterson rolls his eyes and says, "Go ahead and do what you can to improve the world, but meanwhile we all need to toughen up and get on with our lives." "So," say the activists, "you're saying that the suffering of the poor and the oppressed is their fault?" Round and round it goes, a perfect circle of misunderstanding.

The second thing about Peterson is that he is a Jungian in love with myths and archetypes. Like James Campbell or Robert Bly, he is always explaining contemporary things by reference to ancient Egypt or the pyramid on the dollar bill. This includes Jungian ideas about male and female; Peterson firmly believes that men and women are different in ways reflected in ancient stories. One of the best lectures of his I have seen riffs on the story of Peter Pan. The only example of adult masculinity he knows is the toxic one of Captain Hook, so he refuses to grow up, even though that means he can't have a real woman (Wendy) and has to make do with Tinkerbell, "the imaginary fairy of porn."

Like most modern Jungians Peterson draws on evolutionary psychology to buttress his views. He is always referring to dominance hierarchies, submissive gestures, reproductive success, the whole vocabulary of animal behavior. Thus you get passages like this one, from a long explanation of how life is poised between order and chaos:

Chaos the impenetrable darkness of a cave and the accident by the side of the road. It’s the mother grizzly, all compassion to her cubs, who marks you as potential predator and tears you to pieces. Chaos, the eternal feminine, is also the crushing force of sexual selection. Women are choosy maters. … Most men do not meet female human standards.And the third thing about Peterson, the thing that gives a hard edge to all his teaching, is his Nietzschean individualism: his insistence that only individuals matter, and that our only mission in life is to be a good and successful one, rather than a bad failure.

Your group identity is not your cardinal feature. That’s the great discovery of the west. That’s why the west is right. And I mean that unconditionally. The west is the only place in the world that has ever figured out that the individual is sovereign. And that’s an impossible thing to figure out. It’s amazing that we managed it. And it’s the key to everything that we’ve ever done right.Peterson uses this whole structure to carry out what one might call a therapeutic ministry to young western men. He is teaching, he says, "how not to be pathetic." If you want a woman, stop whining about how impossible they are and become the kind of man they want. If you want a job, become the kind of person employers want to hire. If you want anything at all, get out of your basement and get to work. You should, he says, consider yourself on a heroic mission:

Burden yourself with so much responsibility that you can barely stand, and then you'll get stronger trying to lift it up.The first rule in his new book, 12 Rules for Life, is "Stand up straight with your shoulders back." Posture, he says (with a full dose of both Jungian story telling and ethology) is a metaphor for how you live, and standing up straight means living with confidence, bearing your burdens proudly, treating others well, refusing to bend to bullies, and so on.

Peterson is especially interested in the dark side of our personalities, for good Jungian reasons. Until we confront and incorporate the dark, destructive sides of our natures, we are incomplete. In another video I watched, but have lost the link to, Peterson says you don't want to be the person who can't be cruel. Those people are weak and easily bullied. You also don't want to be a cruel person. You want to be the person who can be cruel but then does not; who is not afraid of his murderous darkness but has drawn it forth and mastered it. Weakness is not virtue; only the strong can truly be virtuous. And Peterson likes to display his "strength," as here, when he questions a call to treat everyone with respect:

You bloody don't get to demand my respect.Like many psychologists he is fascinated by the people who perpetuate genocide, and wonders what differentiates them from those who refuse to join in the slaughter:

I think I’m someone who is properly terrified. I’ve thought a lot about very terrible things. And I read history as the potential perpetrator – not the victim. That takes you to some very dark places. . . .So here comes this white guy telling young men that they need to get in touch with their dark sides and move up the dominance hierarchy and learn how to get what they want from life, including women; who believes men and women are very different for the most profound possible reasons, and rolls his eyes at trans people; and who has besides a suspicious fascination with Hitler. No wonder he infuriates leftists, despite his support for national health care, high taxes on the rich, strong environmental protections, and other liberal causes.

“Nietzsche pointed out that most morality is cowardice. There’s absolutely no doubt that that is the case. The problem with ‘nice people’ is that they’ve never been in any situation that would turn them into the monsters they’re capable of being.”

So if “nice people” get the chance to disguise their dark impulses from themselves, are they likely to indulge those impulses? “Yes. And a bit of soul-searching would allow them to determine in what manner they are currently indulging them.”

The fact of our essential darkness may, perhaps, be seen transparently in the flood of hatred, abuse and rage that is now clearly visible on anonymous Twitter feeds. It was “so-called normal people”, not sociopaths, who were responsible for the atrocities of Nazism, Stalinism and Maoism. We must not forget, says Peterson, that we are corrupt and pathetic, and capable of great malevolence.

Peterson is a reactionary in some ways, especially about several key questions that are prominent on college campuses. He hates identity politics because his main focus is the therapist's preoccupation with the healthy individual. He hates the whole movement to treat gender as something to be de-emphasized or changed at will because he believes that the eternal masculine and feminine are fundamental to our souls. He hates whining about the 1 percent because he thinks it is envy. He hates post-modernism because he thinks it subordinates truth to politics, and he believes very firmly that certain things are true whether you like them or not.

Plus – and this is the thing that gets the most exclamation points from his Youtube-posting fans – he hates big parts of contemporary progressive discourse because he believes they are hurtful to the young men he is trying to treat:

Women are structured differently from men, for biological necessity, even if it's not a psychological necessity, which it partly is. . . . Women know what they have to do. Men have to figure out what they have to do. And if they have nothing worth living for, then they stay Peter Pans. And why the hell not? . . . Why lift a load if there's nothing in it for you? That's another thing that we're doing to men that's a very bad idea, and to boys. It's like, you're pathological and oppressive. Well, fine then, why the hell am I going to play? If that's the situation, if I get no credit for bearing responsibility, you can bloody well be sure I'm not going to bear it. But then, you know, your life is useless and meaningless, you're full of self contempt and nihilism, and that's not good. . . . You're like a sled dog without a sled to pull, and you're going to tear pieces out of your own leg because you're bored.This I could not agree more with; if your idea of progressive politics is saying that all men or all white people are evil oppressors, then I want nothing to do with your agenda, and I hate it when people say things like that to my sons.

When Peterson does talk about politics directly he is much less compelling than when he talks about myth or psychology. In this interview he takes student activists to task for trying to change systems they do not understand. Why, he asks, do students who can't even clean their dorm rooms think they know how to make the country better? It's a strange, managerial approach to politics, as if these things could be done without any ideology or any passion. It is probably true that student activists would make a complete hash of running the government, but without the passion of activists, would anything ever change? Peterson thinks about students from a psychological perspective, and he sees them acting out rebellions against their parents and finding their identity through joining the cool club and so on. All of which is important and true, but still leaves out something vital about political activism in our age.

But as I said, Peterson rarely talks directly about politics. And yet – and this is what fascinates me –he has ended up in a political storm anyway. Politics and psychology are, I suppose, different ways of looking at the same thing: how people live together. So a way of understanding psychology necessarily has some political implications, and vice versa. I don't think, though, that we understand at all how to make them work together. Right now we have politics that demand we act rationally and psychology that explains why we never do; does that make any sense? Can we imagine a political system that both promotes mental health and draws realistically on the strengths and weaknesses of our minds?

For now, no.

Johann Gottfried Steffan

Johann Gottfried Steffan (1815-1905) was a prominent Swiss landscape painter. He worked for a long time and left more than 500 paintings. Alp with Brook and Goatherd.

His Alpine paintings mostly look like these, with a dark, brooding, Romantic air. Scene in the Ramsgau near Berechtsgaden, 1874.

Study of clouds.

But when he traveled to Italy he left all the Romantic shadow behind and painted in a much lighter, brighter style, mainly using watercolors instead of oils. I love this painting, but when I did a quick search for Steffan's other paintings the first twenty that came up were all in the dark, Romantic mode, and I wondered if there had been some mistake. But the same man did all of them. Cadennabia, Lake Como.

Venice, Rio San Barnaba.

Venice, Painters' Corner.

Balbianello, Lake Como.

Lerici.

Venice, view toward Dogana. I wonder if his mood and personality changed as much in Italy as his style did.

His Alpine paintings mostly look like these, with a dark, brooding, Romantic air. Scene in the Ramsgau near Berechtsgaden, 1874.

Study of clouds.

But when he traveled to Italy he left all the Romantic shadow behind and painted in a much lighter, brighter style, mainly using watercolors instead of oils. I love this painting, but when I did a quick search for Steffan's other paintings the first twenty that came up were all in the dark, Romantic mode, and I wondered if there had been some mistake. But the same man did all of them. Cadennabia, Lake Como.

Venice, Rio San Barnaba.

Venice, Painters' Corner.

Balbianello, Lake Como.

Lerici.

Venice, view toward Dogana. I wonder if his mood and personality changed as much in Italy as his style did.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

Another Cretan Snake Goddess

Teracotta goddess statue, found in Gortys, Crete, dated to 1300-1200 BC. Now in Heraklion.

I can't remember ever seeing this before, which is strange, since it seems like an important piece of evidence in the ongoing dispute over the reality of snake-handling Minoan goddesses/priestesses. But I think I may have posted a photo of the display case where this sits in the Heraklion Museum, back in 2016; I think this was cut off on the right side. Fascinating, the things we just miss seeing.

Gandhi on Cultural Appropriation

I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be closed. I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible.

– one of the quotations carved on the Gandhi statue on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington

– one of the quotations carved on the Gandhi statue on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

The Syrian Mess

In Syria, our NATO allies the Turks are, with Russian help, attacking our other allies the Syrian Kurds, who did much of the hard fighting against the Islamic State around its old capital. We are paralyzed, caught in a web of our own making: we can't fight the Turks, because they are in NATO and we depend on our Turkish air base to keep our Middle Eastern wars going; we can't fight the Russians because we agreed to their setting in up Syria, and anyway we don't want a war with Russia, and on what basis could we complain about their helping our Turkish allies? We can't abandon the Kurds because they are our only really reliable friends in the whole godforsaken region, plus we would feel like cads for ditching them after working so closely with them for so long, not to mention the whole "losing face", "not following through on our commitments" thing that matters so much to so many American foreign policy types. And, we can't broker a peace deal in Syria because that would mean recognizing the Syrian government, which we have been saying for years is an illegitimate tyranny.

Near as I can tell, our Syrian policy is to keep muddling along until a democratic, human-rights-respecting, pro-America, pro-Israel, anti-Iran, anti-terrorist government miraculously appears in Damascus. Meanwhile, people continue to be blown up on a regular basis, and the whole region from Manchester to Amman is in crisis over what to do about refugees thrown up by this and other wars. There's no use blaming Trump's people for this, because Obama's had no idea what to do, either, and ended up focusing on the Islamic State because that was one problem we felt like we could solve. They seem to be pretty much beaten. But Syria's ordeal seems likely to stretch on for decades.

Sigh.

On the map above, territory controlled by the Syrian government is in red, Kurdish territory in yellow, other rebels in green, and the remnants of the Islamic State in gray.

Near as I can tell, our Syrian policy is to keep muddling along until a democratic, human-rights-respecting, pro-America, pro-Israel, anti-Iran, anti-terrorist government miraculously appears in Damascus. Meanwhile, people continue to be blown up on a regular basis, and the whole region from Manchester to Amman is in crisis over what to do about refugees thrown up by this and other wars. There's no use blaming Trump's people for this, because Obama's had no idea what to do, either, and ended up focusing on the Islamic State because that was one problem we felt like we could solve. They seem to be pretty much beaten. But Syria's ordeal seems likely to stretch on for decades.

Sigh.

On the map above, territory controlled by the Syrian government is in red, Kurdish territory in yellow, other rebels in green, and the remnants of the Islamic State in gray.

If Not Liberalism, What?

František Kupka, Path of Silence, 1903

Damon Linker has given some more attention to one of the year's big books, Patrick Deneen's Why Liberalism Failed. Linker calls the book "breathtakingly radical."

Deneen is talking about "liberalism" in the broadest sense, basically the whole Enlightenment project: freedom, equality, reason, science, the overturning of traditional hierarchies, the smashing of traditional societies and their rules, etc. Deneen's thesis is that the Enlightenment has run its course and left us lonely, spiritually vacant, and miserable. The harder we fight to cast off every possible limitation on our freedom, the more we wonder what to do with it. Rod Dreher summed up Deneen's book as arguing

that liberalism is degenerating to the point where — to put it crudely — more and more people see no real purpose to life beyond shopping and sex.This may be true. It is, after all, the basic criticism that has been made of the Enlightenment since it first got going. It was put forward in more sophisticated terms by a slew of nineteenth- and twentieth-century philosophers: Kierkegaard, Nietzche, Marx, Marcuse. Sartre wrote a famous play in which he likened freedom to nausea.

So, yeah, freedom brings troubles, and it is probably fair to say that it makes some people miserable. But then some people have always been miserable. Whether more people are miserable now than in the sixteenth century is a hard question, but personally I would rather live now.

Deneen also has a particular criticism of our political moment:

As liberalism has "become more fully itself," as its inner logic has become more evident and its self-contradictions manifest, it has generated pathologies that are at once deformations of its claims yet realizations of liberal ideology. A political philosophy that was launched to foster greater equality, defend a pluralist tapestry of different cultures and beliefs, protect human dignity, and, of course, expand liberty, in practice generates titanic inequality, enforces uniformity and homogeneity, fosters material and spiritual degradation, and undermines freedom.So pushing freedom too hard leads to oppression, like persecuting bakers who aren't sufficiently on board with gay rights. Again, Deneen is far from the first to notice this problem; I suggest Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1792) for a basic primer. Not so long ago Simone de Beauvoir suggested that it be made illegal for any mother to stay home with her children, since this would prevent women from achieving full equality in the work force. The temptation to ban things we don't like is always with us.

But anyone who thinks Christian bakers in 21st-century America are less free than medieval serfs is simply mad.

My readers know that I wrestle with these questions all the time. But I always come back to this: what is the alternative? Moralistic dictatorship along the lines of Franco's Spain? Or repressive religious democracy like in 1950s Ireland? Soviet Russia? Saudi Arabia? The real-world examples of people trying hard to "preserve traditional values" and "strengthen communities" end up pretty grim. They have the things that really make modern life awful – bureaucracy, regimentation, politicization, mass-produced sameness – but without the artistic, intellectual, and cultural ferment that makes our age exciting and fun. And without the cash that smooths over many tribulations, since they always seem to clamp down on the economy when they try to clamp down on sin.

I acknowledge that the post-Enlightenment world has problems. But I am not sure they are worse than any other age's problems, or that there is any practical alternative to the cult of individual freedom as a way to organize our world.

Monday, January 22, 2018

The Yakima Crack

Above the Yakima River near the town of Union Gap, Washington, a crack has appeared in a mountain:

The fissure was first spotted in October on Rattlesnake Ridge in south central Washington State, overlooking Interstate 82 and the Yakima River. Since then, a 20-acre chunk of mountainside — roughly four million cubic yards of rock, enough to fill 25 football stadiums to the top of the bleachers, eight stories up — has been sliding downhill. Geologists can measure its current speed — about two and a half inches a day — but they cannot say for certain when, or if, it might accelerate into a catastrophe. And they are powerless to stop it.Geologists think the mass will break free and collapse between late February and early April. Must be pretty creepy to live anywhere nearby.

“The mountain is moving, and at some point this slide will happen — it’s just a matter of when,” said Arlene Fisher-Maurer, the city manager in Union Gap, population about 7,000, just north of the ridge.

Sunday, January 21, 2018

Slipwares from Revolutionary Philadelphia

I wrote before about the amazing eighteenth-century artifacts recovered from the site of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. Here are a few more, slipware dishes found in a privy. These were everyday dishes, used both in the kitchen and at the table.

The Strangeness of the New Testament

David Bentley Hart, Eastern Orthodox scholar, has published a new translation of the New Testament that he calls "subversively literal." As he explains in this passage on the teachings of Paul, the New Testament does not literally say what we interpret it to say:

Questions of law and righteousness, however, are secondary concerns. The essence of Paul’s theology is something far stranger, and unfolds on a far vaster scale. For Paul, the present world-age is rapidly passing, while another world-age differing from the former in every dimension – heavenly or terrestrial, spiritual or physical – is already dawning. The story of salvation concerns the entire cosmos; and it is a story of invasion, conquest, spoliation and triumph. For Paul, the cosmos has been enslaved to death, both by our sin and by the malign governance of those ‘angelic’ or ‘daemonian’ agencies who reign over the earth from the heavens, and who hold spirits in thrall below the earth. These angelic beings, whom Paul calls Thrones and Powers and Dominations and Spiritual Forces of Evil in the High Places, are the gods of the nations. In the Letter to the Galatians, he even hints that the angel of the Lord who rules over Israel might be one of their number. Whether fallen, or mutinous, or merely incompetent, these beings stand intractably between us and God. But Christ has conquered them all.The contrast between the early Christian cultists and their sane, proper, moderate descendants is quite stark.

In descending to Hades and ascending again through the heavens, Christ has vanquished all the Powers below and above that separate us from the love of God, taking them captive in a kind of triumphal procession. All that now remains is the final consummation of the present age, when Christ will appear in his full glory as cosmic conqueror, having ‘subordinated’ (hypetaxen) all the cosmic powers to himself – literally, having properly ‘ordered’ them ‘under’ himself – and will then return this whole reclaimed empire to his Father. God himself, rather than wicked or inept spiritual intermediaries, will rule the cosmos directly. Sometimes, Paul speaks as if some human beings will perish along with the present age, and sometimes as if all human beings will finally be saved. He never speaks of some hell for the torment of unregenerate souls.

The new age, moreover – when creation will be glorified and transformed into God’s kingdom – will be an age of ‘spirit’ rather than ‘flesh’. For Paul, these are two antithetical principles of creaturely existence, though most translations misrepresent the antithesis as a mere contrast between God’s ‘spirit’ and human perversity. But Paul is quite explicit: ‘Flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom.’ Neither can psychē, ‘soul’, the life-principle or anima that gives life to perishable flesh. In the age to come, the ‘psychical body’, the ‘ensouled’ or ‘animal’ way of life, will be replaced by a ‘spiritual body’, beyond the reach of death.

A Mormon Archaeologist Loses his Faith

Fascinating little essay by Lizzie Wade on Thomas Ferguson, a Mormon who explored southern Mexico's archaeological sites in the 1940s and 1950s, searching for proof of Mormon teaching about ancient civilizations in the Americas:

After years of studying maps, Mormon scripture, and Spanish chronicles, Ferguson had concluded that the Book of Mormon took place around the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the narrowest part of Mexico. He had come to the jungles of Campeche, northeast of the isthmus, to find proof.Ferguson and his New World Archaeological Foundation did turn up plenty of ancient cities, but no evidence that they were settled by Hebrews or Egyptians as the Book of Mormon says. He eventually realized that he could not find this evidence because it did not exist – because the Book of Mormon is fiction. As he wrote to a friend,

As the group's local guide hacked a path through the undergrowth with his machete, that proof seemed to materialize before Ferguson's eyes. "We have explored four days and have found eight pyramids and many lesser structures and there are more at every turn," he wrote of the ruins he and his companions found on the western shore of Laguna de Términos. "Hundreds and possibly several thousand people must have lived here anciently. This site has never been explored before."

Ferguson, a lawyer by training, did go on to open an important new window on Mesoamerica's past. His quest eventually spurred expeditions that transformed Mesoamerican archaeology by unearthing traces of the region's earliest complex societies and exploring an unstudied area that turned out to be a crucial cultural crossroads. Even today, the institute he founded hums with research. But proof of Mormon beliefs eluded him. His mission led him further and further from his faith, eventually sapping him of religious conviction entirely. Ferguson placed his faith in the hands of science, not realizing they were the lion's jaws.

Right now I am inclined to think that all of those who claim to be ‘prophets’, including Moses, were without a means of communication with deity.That's the thing about science. Sometimes it may tell you what you want to hear, but more often, in spiritual terms, it produces only howls from the void.

Saturday, January 20, 2018

Friday, January 19, 2018

To Beat Trump, Focus on the Issues

Matt Yglesias:

Trump’s opponents should note that the past couple of weeks of intense debate over the president’s “fitness” for office, concluding in a new round of “Trump is a bigot” takes, have corresponded with his approval ratings getting steadily better.This is what I think. In 2016 Trump's opponents spent too much time sputtering about how impossible he is and not enough pounding him on the issues. Hillary tried, but too many voters tuned her out. The Democrats need a candidate who is woke enough on race and immigration issues to get the nomination but will focus much more on the economy and health care.

He bottomed out in mid-December at the height of the debate over the Republican tax bill, and has edged up by 4 or 5 points since then.

And it actually makes perfect sense. Being a racist (or totally uninformed about policy issues) may be in some sense a graver sin than favoring tax policy tilted in favor of the very rich. But in political terms, most Americans are white but few Americans are very rich, so a focus on the idea that Trump is excessively cruel to nonwhites moves fewer votes than the idea that Trump is excessively focused on the whims of plutocrats. . . .

To students of nativist demagogues abroad, like Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, this is no surprise. In the wake of Trump’s win, the Italian-born economist Luigi Zingales reflected on the lessons of the two Italian politicians who’d managed to beat Berlusconi, observing, “Both of them treated Mr. Berlusconi as an ordinary opponent. They focused on the issues, not on his character.”

Trump’s opponents would be wise to do the same — Trump’s brand of white identity politics has real consequences, but the overall Trump Show is basically a con that masks an agenda that’s bad for almost everyone.

Thursday, January 18, 2018

Religion and Decadence

From the interview Tyler Cowen (an agnostic) did with Ross Douthat (a conservative Catholic):

I find this dismissive and irritating. I am not particularly interested in either getting ahead or having fun, and I reflect continuously. I simply don't find that the teaching of half-mad Iron Age prophets provide a very complete understanding of the universe or my own place in it.

COWEN: When you see how much behavior Islam or some forms of Islam motivate, do you envy it? Do you think, “Well, gee, what is it that they have that we don’t? What do we need to learn from them?” What’s your gut emotional reaction?I like Cowen's question, but Douthat's answer get me to one of the things I dislike most about religion: the assumption that secular people are shallow, that they never think about the "important questions." I first encountered this in C.S. Lewis' The Screwtape Letters, in which secular people are too obsessed with getting ahead or having fun to take things seriously, and the lower-ranking demon is instructed to make sure they stay too busy with one or the other to pause and reflect. Reflection is dangerous, the senior demon says, because it might lead people to God.

DOUTHAT: I think that Western civilization is decadent, and that decadence has virtues — among them, the absence of the kind of massive bloody civil wars currently roiling the Middle East. But, at the same time, there is a sense in which, yeah, there are parts of Islam that are closer to asking the most important questions about existence than a lot of people are in the West. And asking important questions carries major risks and incites levels of extremism that we’ve tamped down and put away, but that desire for the extreme and the absolute and the truth about things that animates some of the best and some of the worst parts of Islam, I think it’s better for human beings to have that desire than not.

I find this dismissive and irritating. I am not particularly interested in either getting ahead or having fun, and I reflect continuously. I simply don't find that the teaching of half-mad Iron Age prophets provide a very complete understanding of the universe or my own place in it.

Today's World Economic Number

Bloomberg:

Between 2000 and 2015, global clothing production doubled, while the average number of times that a garment was worn before disposal declined by 36 percent. In China, it declined by 70 percent.These numbers, along with new technologies that make it cheaper to make new cloth than to recycle old, has people worried that more and more clothes are going to end up in landfills.

Who's Turning Against Trump? Women

From the Atlantic's account of a big new poll from SurveyMonkey:

I think developments in the war of the sexes are potentially more explosive. I will bet now that the 2020 election produces the biggest gender gap in US voting history; that is certainly what the polls predict. Trump's election seems to have crystallized feminist discontent with men of a certain sort, and you see that discontent bursting out all over.

I regard these conflicts as fundamental and very difficult to solve, so I wonder where all this is leading. The anger that pours forth from men's rights activists and some of their feminist opposites troubles me; after all, it's going to be hard to continue the species if men and women can't get along, and young men without women in their lives (a rapidly growing group) are just plain dangerous. I guess the root of my rambling here is that I regard racism as a problem that could be solved, or at least for which I can imagine a solution. I am not at all sure that the problems of men and women, of marriage, of raising children in a world where everyone is supposed to have a career, ever can be solved, and I certainly cannot imagine a realistic solution. So to see these conflicts brought to the center of the national discourse makes me wonder what is in store for us. I am certain that this will make many men and some women even more loyal to Trump, who stands strongly for the old, patriarchal model of the family. I hope it makes more women turn against him. But I am not really sure that is how things will play out.

Layering in gender and age underscores voters’ retreat. Trump in 2016 narrowly won younger whites. But he now faces crushing disapproval ratings ranging from 62 percent to 76 percent among three big groups of white Millennials: women with and without a college degree, and men with a degree. Even among white Millennial men without a degree, his most natural supporters, Trump only scores a 49-49 split.Among minority men, Trump's position is essentially unchanged or has even improved slightly; I guess nothing he has said has surprised them. But minority women hate him:

Trump’s support rapidly rises among blue-collar white men older than 35 and spikes past two-thirds for those above 50. But his position has deteriorated among white women without a college degree. Last year he carried 61 percent of them. But in the new SurveyMonkey average, they split evenly, with 49 percent approval and 49 percent disapproval. His approval rating among non-college-educated white women never rises above 54 percent in any age group, even those older than 50. From February through December, Trump’s approval rating fell more with middle-aged blue-collar white women than any other group.

Among African Americans and Hispanics, reactions to Trump depend more on gender than age or education. In every age group, and at every level of education, about twice as many African American men as women gave Trump positive marks. In all, 23 percent of black men approved of Trump’s performance versus 11 percent of black women. “The outlier here isn’t [black] men … it’s [black] women, where you have near-universal disapproval of Trump,” said Cornell Belcher, a Democratic pollster who studies African American voters. Still, black men are one of the few groups for which Trump’s 2017 average approval rating significantly exceeds his 2016 vote share.When it comes to race, I think Trump represents a defensive spasm from the past, which is slowly disappearing. That anti-racist protesters always hugely outnumber the racists in any recent confrontation shows me that things will continue to move in the same direction. The nation's dramatic shift over the Civil War and its commemoration seems to me an important sign; heck, as Youtube recently reminded me, in my lifetime radical leftist Joan Baez recorded "The Night they Drove Old Dixie Down."

I think developments in the war of the sexes are potentially more explosive. I will bet now that the 2020 election produces the biggest gender gap in US voting history; that is certainly what the polls predict. Trump's election seems to have crystallized feminist discontent with men of a certain sort, and you see that discontent bursting out all over.

I regard these conflicts as fundamental and very difficult to solve, so I wonder where all this is leading. The anger that pours forth from men's rights activists and some of their feminist opposites troubles me; after all, it's going to be hard to continue the species if men and women can't get along, and young men without women in their lives (a rapidly growing group) are just plain dangerous. I guess the root of my rambling here is that I regard racism as a problem that could be solved, or at least for which I can imagine a solution. I am not at all sure that the problems of men and women, of marriage, of raising children in a world where everyone is supposed to have a career, ever can be solved, and I certainly cannot imagine a realistic solution. So to see these conflicts brought to the center of the national discourse makes me wonder what is in store for us. I am certain that this will make many men and some women even more loyal to Trump, who stands strongly for the old, patriarchal model of the family. I hope it makes more women turn against him. But I am not really sure that is how things will play out.

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

Real Cost of Solar and Wind Power Still Falling

Last year XCel Energy put out a request for bids on new electric power generation in Colorado, and their summary of the bids was recently released. This is actual bids from power generation firms, not some analyst's projections, all to be online by 2023. In total XCel received 350 bids, so there is a lot of interest in building these plants.

The cost of electricity from existing coal plants in the US is around $40 per MWH. The average bids received by XCel for renewable power were as follows:

Wind: $18.10/MWH

Wind plus Battery Storage: $21.00/MWH

Solar: $29.50/MWH

Solar plus Battery Storage: $36.00/MWH

Wind/Solar/Battery Storage: $30.60/MWH

These numbers are significantly lower than bids from just two years ago. It's the added battery storage numbers that are key, because to use a lot of renewable power you need either fossil fuel back-up or lots of storage. The bid sheet doesn't say how much storage these bids include, but at any rate you can now build some substantial amount of battery back-up into a new solar/wind system and still end up with a lower price than you get from an already up-and-running coal plant. This makes it seem that the price of battery storage is falling fast, and that power generation companies are betting that this will continue.

One reason that power generation firms are interested in the solar/wind + battery storage formula is that they can charge a higher price for the more reliable power than they could for straight solar or wind, so there's a case of market incentives aligning with what the people clearly need.

Incidentally the amount of coal burned in the US fell by 2% last year, despite Trump and rising demand for electricity; these analysts calculated that if Kentucky replaced all their coal-fired plants with a combination of natural gas and wind, the average electricity bill would fall by 10%, even including the cost of building all the new plants.

The cost of electricity from existing coal plants in the US is around $40 per MWH. The average bids received by XCel for renewable power were as follows:

Wind: $18.10/MWH

Wind plus Battery Storage: $21.00/MWH

Solar: $29.50/MWH

Solar plus Battery Storage: $36.00/MWH

Wind/Solar/Battery Storage: $30.60/MWH

These numbers are significantly lower than bids from just two years ago. It's the added battery storage numbers that are key, because to use a lot of renewable power you need either fossil fuel back-up or lots of storage. The bid sheet doesn't say how much storage these bids include, but at any rate you can now build some substantial amount of battery back-up into a new solar/wind system and still end up with a lower price than you get from an already up-and-running coal plant. This makes it seem that the price of battery storage is falling fast, and that power generation companies are betting that this will continue.

One reason that power generation firms are interested in the solar/wind + battery storage formula is that they can charge a higher price for the more reliable power than they could for straight solar or wind, so there's a case of market incentives aligning with what the people clearly need.

Incidentally the amount of coal burned in the US fell by 2% last year, despite Trump and rising demand for electricity; these analysts calculated that if Kentucky replaced all their coal-fired plants with a combination of natural gas and wind, the average electricity bill would fall by 10%, even including the cost of building all the new plants.

How Much of the Opioid Epidemic is Caused by Economic Hard Times?

Not very much, according to these academics:

This is just one study, but I would not be surprised if it is right. But not because I think the epidemic has nothing to do with “despair.” As we know, in our wealthy world economic troubles manifest largely in psychological terms, that is, a rise in the unemployment rate from 5% to 9% can make a lot more than 4% of the people miserable. So a whole community's sense that times are bad and the future is bleak might not show up very clearly in the raw economic numbers.

Take the paradigmatic case of the coal country in southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky. These are poor areas, but they have always been poor. It's just that the industries they did have -- coal mining, manufacturing -- are rapidly declining. This makes their “medium-run economic conditions” only a little worse than they were, but it has a huge impact on the overall mood of those places. They are depressed and distressed, even if their median income is much higher than what we would consider a boom town in Nigeria or even Mexico.

Of course opiates are a big problem even in wealthy areas, which gets me to what “deaths of despair” would actually mean. I agree that the main cause of the epidemic is not economic hard times but the huge increase in the supply of the drugs. But why did people want them? Why was there, in economic terms, a huge unmet demand for opiates that changes in how doctors treat pain went a long way toward filling?

I don't think people take these drugs for fun. They take them because they are unhappy, stressed, and in pain. They are self-medicating conditions we could call anxious depression, chronic pain, chronic fatigue, or other such medical-sounding terms, but which I would be equally happy to call despair. I don't mean to say that many drug users don't have physical problems, from bad backs to chemical imbalances in their brains; I just think that when drug use runs rampant through whole communities, a broader understanding of the cause is called for.

If it is true that the main cause of the current opioid epidemic is increased supply, that makes the essential question very clear: why do people need drugs in the first place? And, is there anything we could do to make their lives better – less stressful, less painful, less depressing?

The United States is in the midst of a fatal drug epidemic. This study uses data from the Multiple Cause of Death Files to examine the extent to which increases in county-level drug mortality rates from 1999-2015 are due to “deaths of despair”, measured here by deterioration in medium-run economic conditions, or if they instead are more likely to reflect changes in the “drug environment” in ways that present differential risks to population subgroups. A primary finding is that counties experiencing relative economic decline did experience higher growth in drug mortality than those with more robust growth, but the relationship is weak and mostly explained by confounding factors. In the preferred estimates, changes in economic conditions account for less than one-tenth of the rise in drug and opioid-involved mortality rates.What they find instead is that the biggest factor influencing drug use in any community is the availability and cost of drugs.

This is just one study, but I would not be surprised if it is right. But not because I think the epidemic has nothing to do with “despair.” As we know, in our wealthy world economic troubles manifest largely in psychological terms, that is, a rise in the unemployment rate from 5% to 9% can make a lot more than 4% of the people miserable. So a whole community's sense that times are bad and the future is bleak might not show up very clearly in the raw economic numbers.

Take the paradigmatic case of the coal country in southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky. These are poor areas, but they have always been poor. It's just that the industries they did have -- coal mining, manufacturing -- are rapidly declining. This makes their “medium-run economic conditions” only a little worse than they were, but it has a huge impact on the overall mood of those places. They are depressed and distressed, even if their median income is much higher than what we would consider a boom town in Nigeria or even Mexico.

Of course opiates are a big problem even in wealthy areas, which gets me to what “deaths of despair” would actually mean. I agree that the main cause of the epidemic is not economic hard times but the huge increase in the supply of the drugs. But why did people want them? Why was there, in economic terms, a huge unmet demand for opiates that changes in how doctors treat pain went a long way toward filling?

I don't think people take these drugs for fun. They take them because they are unhappy, stressed, and in pain. They are self-medicating conditions we could call anxious depression, chronic pain, chronic fatigue, or other such medical-sounding terms, but which I would be equally happy to call despair. I don't mean to say that many drug users don't have physical problems, from bad backs to chemical imbalances in their brains; I just think that when drug use runs rampant through whole communities, a broader understanding of the cause is called for.

If it is true that the main cause of the current opioid epidemic is increased supply, that makes the essential question very clear: why do people need drugs in the first place? And, is there anything we could do to make their lives better – less stressful, less painful, less depressing?

The Attention we Give to Mass Killers

Study shows that the average mass killer gets $75 million worth of media attention.

The obvious lesson would be that people do it to get famous and we could reduce the problem by ignoring them, but I'm not sure that's true; has anybody read enough about these monsters to find out what part a desire to be famous played in their schemes? And even that result would be ambivalent, like, Timothy McVeigh wanted to make a huge media splash, but that was because he was hoping to touch off a revolution.

Plus, given Americans obsession with such events, I doubt even the most determined, anti-Constitutional censorship would have much effect.

The obvious lesson would be that people do it to get famous and we could reduce the problem by ignoring them, but I'm not sure that's true; has anybody read enough about these monsters to find out what part a desire to be famous played in their schemes? And even that result would be ambivalent, like, Timothy McVeigh wanted to make a huge media splash, but that was because he was hoping to touch off a revolution.

Plus, given Americans obsession with such events, I doubt even the most determined, anti-Constitutional censorship would have much effect.

Tuesday, January 16, 2018

The Bird-Catcher's Cup

Monday, January 15, 2018

Tunnels under the Berlin Wall

Wonderful article in the Times by Christopher Schuetze and Palko Karasz about the old tunnels under the Berlin Wall:

About 75 tunnels were built under the wall during its three-decade existence, many of them around Bernauer Strasse. Residential buildings nearby provided handy shelter for digging and for entering the passages.The story focuses on the archaeological discovery of a tunnel dug for a failed crossing attempt in 1962. After the Wall fell Germans seemed determined to erase every trace of its existence, but these days there is some interest in commemorating the Wall and preserving bits of it, perhaps including this tunnel.

One escape that received widespread attention was filmed by NBC in 1962. The network provided money for an effort by students in West Berlin to connect two cellars on either side of the wall. The resulting documentary, called “The Tunnel,” related the escape of 29 men, women and children, and it raised questions about the journalistic ethics involved.

In the autumn of 1964, 57 people from the East escaped through a tunnel that started in a disused courtyard bathroom [shown above]. But this escape marked a turning point. An East German border guard was killed in a gunfight between the security forces and those helping the escape on the Western side. The 21-year-old guard, Egon Schultz, became a hero in the East after his death, leading many in the West to question the wisdom of promoting such crossings.

Sunday, January 14, 2018

Moving the Vatican Obelisk, 1585

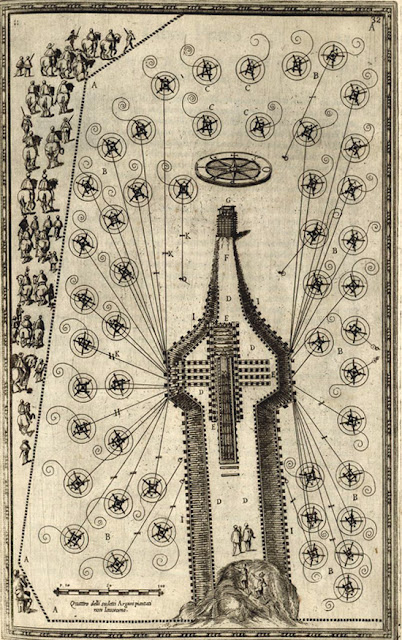

In 1585, the "Vatican obelisk" was moved 275 feet (83 m) to the square in front of Saint Peter's Basilica. Architect Domenico Fontana designed a wooden tower that would be constructed around the obelisk, connected to a system of ropes and pulleys. The move, including construction of the tower, took 13 months. Seventy-two horses and more than 900 men worked on the project.

This obelisk was brought to Rome from Egypt in AD 37 by emperor Caligula. It is 85 feet tall (25.5 m) and weighs 330 tons. The Romans stole so many Egyptian obelisks that there are more in Rome (13) than in Egypt. Nobody knows how the ancient Romans or Egyptians moved and erected these huge monuments, but Fontana's drawings show one way it could be done with pre-modern technology. This illustration is from the Getty.

Searching around I found more images from this same document.

Including these that show how forty capstans placed around the square were used to control the ropes.

This obelisk was brought to Rome from Egypt in AD 37 by emperor Caligula. It is 85 feet tall (25.5 m) and weighs 330 tons. The Romans stole so many Egyptian obelisks that there are more in Rome (13) than in Egypt. Nobody knows how the ancient Romans or Egyptians moved and erected these huge monuments, but Fontana's drawings show one way it could be done with pre-modern technology. This illustration is from the Getty.

Searching around I found more images from this same document.

Including these that show how forty capstans placed around the square were used to control the ropes.

Albert Saverys, The River Lys in Winter

Three paintings with the same title by Belgain painter Albert Saverys (1886-1964). The one at top is from 1950.

Friday, January 12, 2018

The Berthouville Treasure

Unlike the other Roman silver treasures I have featured here, the trésor de Berthouville was not hidden from invading barbarians as the late empire collapsed; it dates to around 200 CE.

There was plenty of trouble in the empire that could have led to its being hidden; but since order was eventually restored in Gaul, why wasn't the treasure dug up again? Several of the pieces have text scratched on them indicating that they were gifts to the god Mercury, and not all from the same person. Thus the idea that this collection was a temple treasury. Again, though, why would it have been left in the ground? There are actually three such hoards known from Gaul and Britain, although this is the largest and most valuable.

Archaeology showed that the find was near a complex of small temples and shrines. So maybe this was buried as a community's gift to the gods.

The images are the usual classical stuff: scenes from the Trojan War and the life of Hercules, bits of myth, Bacchic rituals.

Here is Omphale, reclining on Hercules' lion skin.

Interesting statue of Mercury.

There are 93 pieces in the hoard, including some small appliques; the total weight is about 25 kg, or 60 pounds. Buried silver can easily decay to dust in just a century, so I find it amazing that so much survives from the ancient world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)