Wednesday, October 31, 2018

That Out of Touch Elite in Congress

Yet another study shows that politicians are largely indifferent to what the public wants:

But my dealings with politicians have impressed on me that they are not analytical people. They are people people who thrive on fact-to-face interactions. The opinions that matter to them are the ones their friends and supporters express when they meet. Many of them seem to have serious attention deficit issues when it comes to policy, especially reading about policy. Some are obsessive readers of polls, but not all are; as you may have noticed some of them regularly denounce polls as silly and say the size of their rallies or their mail bags are better signs of what the public really thinks. I don't think they are all just trying to change the subject; I think many of them really form their view of "the public" much more from what they see and feel than what they read.

In a research paper, we compared their responses with our best guesses of what the public in their districts or states actually wanted using large-scale public opinion surveys and standard models. Across the board, we found that congressional aides are wildly inaccurate in their perceptions of their constituents’ opinions and preferences.This has to be taken with a grain of salt. All good politicians know that what people tell pollsters about issues and how they vote are two different things. A good example is that most Republicans will tell pollsters they care about the deficit, even though hardly any have voted as if they did since Eisenhower's time. Likewise many democrats support integration as long as it it doesn't involve their own kids' school. So this could be a case of politicians understanding the complexity of the links between policy choices and votes better than pollsters do.

For instance, if we took a group of people who reflected the makeup of America and asked them whether they supported background checks for gun sales, nine out of 10 would say yes. But congressional aides guessed as few as one in 10 citizens in their district or state favored the policy. Shockingly, 92 percent of the staff members we surveyed underestimated support in their district or state for background checks, including all Republican aides and over 85 percent of Democratic aides. . . .

Aides usually assumed that the public agreed with their own policy views.

But my dealings with politicians have impressed on me that they are not analytical people. They are people people who thrive on fact-to-face interactions. The opinions that matter to them are the ones their friends and supporters express when they meet. Many of them seem to have serious attention deficit issues when it comes to policy, especially reading about policy. Some are obsessive readers of polls, but not all are; as you may have noticed some of them regularly denounce polls as silly and say the size of their rallies or their mail bags are better signs of what the public really thinks. I don't think they are all just trying to change the subject; I think many of them really form their view of "the public" much more from what they see and feel than what they read.

Monday, October 29, 2018

Aminidab Seekright v. Ferdinando Dreadnought

I was just reading a quite good history of a property in Virginia, thoroughly researched by someone who knows a lot about the society and customs of the time, when I came across this:

This first time I encountered this error it was made by a poor person who actually went to the index for the District Court and commented, "This Dreadnought was a very litigious person, involved in several suits over the course of the decade in different parts of the county."

Sigh.

It's like saying, "this poor guy John Doe keeps being murdered and left by the side of the road."

There are of course many reasons why you would want to avoid using someone's real name at law, one of which gave us Roe v. Wade. In this case the issue was that to get a writ of ejection (disseisin in Latin) heard in a royal or colonial court you had to allege that it was done by "force and arms," a formula that goes back at least to the 12th century as vi et armis. But "by force and arms against the peace of the king" sounds like a felony, and you don't want to take the risk that someone might be accused of a felony because of your civil suit. First, this might get it transferred back to some local court for trial as an ordinary crime, and you just went to a lot of trouble to get your case into a higher court with more power to enforce its verdicts. Second, making a false accusation of felony was itself a crime, punishable by a large fine. So to avoid the risk that criminal matters might complicate your case, you invented imaginary people, Ferdinando Dreadnought to commit the assault and Aminidab Seekright to make the accusation.

By the 18th century this was all just formulaic, but English lawyers loved their formulas. Many Americans probably learned to bring suits this way from William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), which was the most widely owned non-religious book in the colonies. Blackstone wrote:

I was moved to write this because I did a quick online search for both of our imaginary litigants and did not find anything that explained what this was about. So I wrote it. Of course it's a good idea to know something about any legal system before you draw historical conclusions from law cases, but we don't all have time to learn such arcana. And now maybe that this is online and easily findable future historians will google those strange names before they write their books and avoid this mistake.

Three hundred and fifty acres of the tract of land that was to become the Balls' home had been rented to Aminidab Seekright for a term of ten years by George Carter on April 1, 1799. Aminidab Seekright was already in residence on the farm when the Balls arrived. Ferdinando Dreadnought was hired by Spencer Ball as a "Casual Ejector" to evict Seekright from the Carter farm. This he did with much zeal for Aminidab Seekright filed a complaint with the Dumfries District Court the following month against both George Carter and the Casual Ejector who:Which is all fine and well, except that both Aminidab Seekright and Ferdinando Dreadnought are imaginary persons. These are made-up names, just more baroque versions of John Doe and Jane Roe. Which makes a paragraph a little farther down the page even more amusing:

. . . with force and arms entered into the said demised Premises with the Appurtenances and Ejected the said Aminidab then and there did to the great damage of the said Aminidab and against the Peace and Dignity of the Commonwealth. . .

Aminidab Seekright was indeed an unlucky tenant. Following his ejection, he rented a 200-acre farm from Betty Ball and George Carter's sister, Priscilla Mitchell. He spent four days at this Tenement when Ferdinando Dreadnought appeared and ejected him once again.The poor guy; everywhere he went, that damn Dreadnought kept showing up and ejecting him.

This first time I encountered this error it was made by a poor person who actually went to the index for the District Court and commented, "This Dreadnought was a very litigious person, involved in several suits over the course of the decade in different parts of the county."

Sigh.

It's like saying, "this poor guy John Doe keeps being murdered and left by the side of the road."

There are of course many reasons why you would want to avoid using someone's real name at law, one of which gave us Roe v. Wade. In this case the issue was that to get a writ of ejection (disseisin in Latin) heard in a royal or colonial court you had to allege that it was done by "force and arms," a formula that goes back at least to the 12th century as vi et armis. But "by force and arms against the peace of the king" sounds like a felony, and you don't want to take the risk that someone might be accused of a felony because of your civil suit. First, this might get it transferred back to some local court for trial as an ordinary crime, and you just went to a lot of trouble to get your case into a higher court with more power to enforce its verdicts. Second, making a false accusation of felony was itself a crime, punishable by a large fine. So to avoid the risk that criminal matters might complicate your case, you invented imaginary people, Ferdinando Dreadnought to commit the assault and Aminidab Seekright to make the accusation.

By the 18th century this was all just formulaic, but English lawyers loved their formulas. Many Americans probably learned to bring suits this way from William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), which was the most widely owned non-religious book in the colonies. Blackstone wrote:

The whole of it is at present become a mere matter of form; and John Doe and Richard Roe are always returned as the standing pledges for this purpose. The ancient use of them was to answer for the plaintiff; who in case he brought an action without cause, or failed in the prosecution of it when brought, was liable to an amercement from the crown for raising a false accusation. . . .And there you have it. There was no Amindab Seekright or Ferdinando Dreadnought, nor for that matter was there necessarily any force of arms used against the king's peace. These are just legal formulae.

I was moved to write this because I did a quick online search for both of our imaginary litigants and did not find anything that explained what this was about. So I wrote it. Of course it's a good idea to know something about any legal system before you draw historical conclusions from law cases, but we don't all have time to learn such arcana. And now maybe that this is online and easily findable future historians will google those strange names before they write their books and avoid this mistake.

Jef Lambeaux, The Human Passions

a pile of naked and contorted bodies, muscled wrestlers in delirium, an absolute and incomparably childish concept. It is at once chaotic and vague, bloated and pretentious, pompous and empty. And what if, instead of paying for 300,000 francs of “passions”, the government simply bought works of art?

It is displayed in this purpose-built pavilion in the Cinquantenaire Park of Brussels, where it opened to the public in 1899. There is also a full-sized plaster copy that was made to display at some World's Fair and was most recently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent.

Lambeaux never said what the thing is about; even the title was supplied by the government, not the artist. I find it stunning. Below, more details.

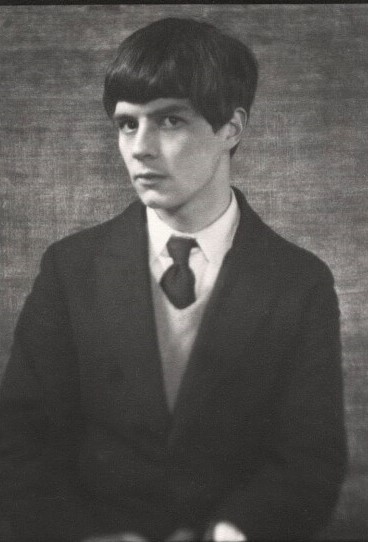

Memories of Steven Runciman

Steven Runciman, famous historian of Byzantium and the Crusades, died in 2001. I just stumbled across these pictures of him in 1925, when he would have been 21, and was reminded of how often our imaginations of older people are inadequate. To me he was always a historian of some previous generation, gray-haired author of magisterial works. But of course he was once young, and as a son of the upper class could indulge his love of Greece and the Middle East by traveling there. I had never imagined him as a young man, exploring Istanbul or Jerusalem or the Greek Islands, and now that I have I will never think of him in the same way again.

Runciman was not really an impractical man, and he served for a time as a diplomat, but to those who knew him he seemed most alive when talking about the past. He seemed, people said, to live more fully in other times than in our own. Runciman's old friend Patrick Leigh Fermor remembered him in an essay for The Spectator, noting how easy it was to imagine him

helping to plot the circumference of the dome of St Sophia, before a late supper with the Empress Theodora, or — he had a soft spot for crowned heads — advising Princess Anna about the accuracy of the Alexiad … shaking his head over the wilder tenets of the Bogomils and persuading a team of iconoclasts to drop their hammers; or calming rebellious prelates at the Council of Ephesus …reasoning with Bohemond at Antioch; or counselling Richard Coeur de Lion about his policy at Acre; or playing chess with Saladin, in his tent; then, a bit later, rallying Bessarion for accepting the filioque clause at the same time as a cardinal’s hat; consoling the eastern Comnenes for the loss of Trebizond; or, under Mount Taygetus, exchanging syllogisms with Gemistos Plethon as they strolled along the future Runciman Street.

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Whatever Works, I Guess

Is there something inherently comforting about blankets, or is it just that we grow up getting warm and falling asleep under them?

Wooden Statues from Chan Chan, Peru

A row of wooden statues, roughly 800 years old, recently uncovered at Chan Chan in northern Peru, the major site of the Chimu Culture:

The statues are 27.5 inches high and made of black wood. They wear beige clay face masks which make for a striking contrast against the darkness of the wood. Each has a circular object on its back that may represent a shield. Of the 20 idols, 19 are intact, one was devoured by termites.Via The History Blog.

The idols are set in two rows of opposing niches occupying a ceremonial corridor of the Utzh An (the Great Chimu palace). The walls are decorated with high reliefs more than 100 feet long, primarily lines of squares reminiscent of a chessboard. There are also wave patterns and images of the “lunar animal,” a dragonlike quadruped accompanied by lunar symbols which is one of the most ancient recurring figures in Peruvian iconography, first appearing in the early Moche culture. The corridor was discovered in June and was filled with soil. It was excavated over the course of months. The statues were first uncovered in September.

Words for Things Best Unmentioned

Linguists have a term, "taboo deformation," for words people use instead of the proper one when the thing to be named is best left unmentioned:

A great example of this is the word “bear,” in English. “Bear” is not the true name of the bear. That name, which I am free to use because the only bear near where I live is the decidedly unthreatening American black bear, is h₂ŕ̥tḱos. Or at least it was in Proto-Indo-European, the hypothesized base language for languages including English, French, Hindi, and Russian. The bear, along with the wolf, was the scariest and most dangerous animal in the northern areas where Proto-Indo-European was spoken. “Because bears were so bad, you didn’t want to talk about them directly, so you referred to them in an oblique way,” says linguist Andrew Byrd.

H₂ŕ̥tḱos, which is pronounced with a lot of guttural noises, became the basis for a bunch of other words. “Arctic,” for example, which probably means something like “land of the bear.” Same with Arthur, a name probably constructed to snag some of the bear’s power. But in Germanic languages, the bear is called…bear. Or something similar. (In German, it’s Bär.) The predominant theory is that this name came from a simple description, meaning “the brown one.”

In Slavic languages, the descriptions got even better: the Russian word for bear is medved, which means “honey eater.” These names weren’t done to be cute; they were created out of fear.

It’s worth noting that not everyone was that scared of bears. Some languages allowed the true name of the bear to evolve in a normal fashion with minor changes; the Greek name was arktos, the Latin ursos. Still the true name. Today in French, it’s ours, and in Spanish it’s oso. The bear simply wasn’t that big of a threat in the warmer climes of Romance language speakers, so they didn’t bother being scared of its true name.

Friday, October 26, 2018

Rick Perlstein, "Nixonland", Part 1: Division

Rick Perlstein's Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (2008) is the best book I have ever read about American politics. Perlstein sets out to explain how the nation went from a landslide for Lyndon Johnson in 1964 to a landslide for Richard Nixon in 1972. His answer is the reaction to the 1960s, and Nixon's ability to ride it. I am going to set aside Perlstein's analysis of Nixon himself for a second post and focus in this one on the broader question of how American politics changed.

In 1964 Lyndon Johnson got 61% of the vote and carried 44 states on a platform that featured Civil Rights, Workers' Rights, and a raft of new programs to combat poverty. Coastal pundits crowed that America was united as never before; everyone but a few "extremists" was on board with the liberal program. In his first State of the Union address Johnson said that Americans were more unified than any other people in the history of freedom.

It wasn't true. Goldwater was a strange, cranky man and a weak candidate, but he still got 38% of the vote, and his supporters included an army of energized young conservatives determined to stop those changes that so excited liberals. As Richard Nixon among many others saw, the position of mainstream liberalism was actually weak. Reforms had already gone too far for many Americans but not nearly far enough for a noisy minority that began to command increasing attention through street protests and riots. Looming in the background was Vietnam, a war few American leaders wanted but almost all were afraid to give up on.

Perlstein begins his narrative of the reaction with the Watts Riots of 1965. On August 11, 1965, a fight between a black motorist and two white policemen ignited an explosion of rage that ran for six days, leading to 34 deaths, more than a thousand serious injuries, and fires that destroyed dozens of buildings. Fire fighters trying to put out the blazes were attacked by rock-throwing mobs who seemed determined to let their own neighborhoods burn to ashes. Eventually 4,000 National Guard troops were deployed to support 1,600 police officers enforcing a strict curfew. Historians estimate that at least 30,000 adults participated in the riots. All of this was broadcast every night into American homes using a new innovation, the news helicopter.

In Perlstein's narrative, the Watts Riots was the first in a series of events that fed fear of chaos in "Middle America." Crime was surging, partly but not entirely because the huge baby boom generation was entering the prime mischief years. New drugs spread, and with them drug abuse. Bombs were set off by a dozen kinds of extremists, of both the left and the right; Puerto Rican nationalists bombed the House of Representatives. More riots broke out, especially after the assassination of M.L. King in 1968. Protests against the war led to repeated confrontations between demonstrators and police, and the mass of the public was not on the side of the protesters; a poll taken the day after National Guard soldiers shot four students at Kent State found that 78% of Americans thought the protesters were to blame.

The country seemed to be spinning out of control. The hippies, the yippies and the radicals were not really very numerous, but they got outsized attention both from those excited by the prospect of change and those horrified by what looked like squalor and barbarism. Fear of communism had eased since 1962 but was still a powerful force, and that some on the left embraced Maoism enraged millions. Families broke up over long hair and beards.

One result of all this, says Perlstein, was a new kind of politics in America. Instead of economic issues that divided the workers from the bourgeoisie, elections would now be fought over cultural issues that divided the hippies from the squares. One of the famous events of those years was the Hard Hat Riot in New York, when 200 construction workers attacked anti-war protesters and were joined by a few dozen Wall Street guys in suits; the workers and their bosses were uniting to fight the revolutionaries. Some Americans these days seem to think that our politics of identity and culture are something new, but Perlstein produces dozens of statements from both the left and the right that could have been made today. In fact one is tempted to say that although the issues have changed, the parties and their attitudes toward each other are exactly the same now as they were in 1968.

What makes the events of the 1960s more tragic than those of our own time is the Vietnam War. All the smart people in America knew by 1966 that the war was an unwinnable mess, including Nixon and his top diplomat, Henry Kissinger. It went on because no way could be found for the US to exit without its tail between its legs. Millions of Americans believed that the war was a test of our resolve as crucial, for us and the world, as World War II; millions of others believed it was a crime and a blunder. The division ran through the whole society, including the military; the prosecution of William Calley for the My Lai massacre led to fist fights in officers' clubs. Vietnam was so big, so important, that it made sensible centrism impossible; you were either for the war or against it. To those who supported the war, those who opposed it were traitors; to those who opposed it, its supporters were murderers. Not that politicians didn't try to fudge the issue; Hubert Humphrey ran for president in 1968 with positions so muddled that nobody really knew what he thought, and Nixon ran by proclaiming that we had to fight the war harder to get to peace faster. But the war was one issue that could not be finessed or swept under the rug, and it kept boiling up to upset any attempt at compromise.

So the stage was set for 1972. The Democrat was George McGovern, a midwestern liberal who came out wholeheartedly against the war. McGovern was for women's rights, Civil Rights, and peace. Nixon was for order and the flag. Nixon was a widely despised figure with few real supporters, and key news about the Watergate break-in and his army of dirty tricksters was breaking throughout the campaign. But in an atmosphere of riot, protest, sexual liberation, and rapid social change, order and the flag won easily.

One of the interesting things about Nixonland is that although it is a book about politics, it says very little about political ideas. This was the criticism made by George Will when he reviewed it in 2008; the conservative movement, he said, was rich in ideas, not just some gut reaction to hippiedom. And that is true. But Perlstein, who wrote a whole book about Barry Goldwater, knows this very well; he simply isn't very interested. He feels, as many people feel about the politics of our own time, that ideas don't seem to matter. What matters is emotion, especially the hate and anger that American factions pour out toward each other.

Which brings me to this question: what did the revolutionary years of the late 1960s and early 1970s accomplish? It is easy to argue that they accomplished nothing. After all the immediate result was a landslide for Nixon, whose downfall only set the stage for Ronald Reagan. Electorally the radical spasms of those years were a disaster for Democrats. What's more they spawned or at least intensified the division of the nation along cultural lines that still bedevils us, making some question whether our democracy can survive.

But I don't think that is the whole story. Politics, as someone once said, is downstream from culture. And culturally, the radicalism of the 1960s had gigantic effects. Women's rights, gay rights, environmentalism, sexual liberation, no-fault divorce; these things have moved into the mainstream and become major parts of our world.

This seems, I guess, to be the modern condition: on the one side the lovers of strangeness and change, and the other those who long for stability and order. On one side the mixers who revel in the multicultural and the multiracial, on the other the people only comfortable when everyone around them is the same. And maybe these things are really ancient, going back to two genetic types that must be mixed in every successful population. But if so, the rapid changes of modernity have brought this to a boil, and we are all living with the consequences.

Nixonland is a great place to read about how all this has happened.

In 1964 Lyndon Johnson got 61% of the vote and carried 44 states on a platform that featured Civil Rights, Workers' Rights, and a raft of new programs to combat poverty. Coastal pundits crowed that America was united as never before; everyone but a few "extremists" was on board with the liberal program. In his first State of the Union address Johnson said that Americans were more unified than any other people in the history of freedom.

It wasn't true. Goldwater was a strange, cranky man and a weak candidate, but he still got 38% of the vote, and his supporters included an army of energized young conservatives determined to stop those changes that so excited liberals. As Richard Nixon among many others saw, the position of mainstream liberalism was actually weak. Reforms had already gone too far for many Americans but not nearly far enough for a noisy minority that began to command increasing attention through street protests and riots. Looming in the background was Vietnam, a war few American leaders wanted but almost all were afraid to give up on.

Perlstein begins his narrative of the reaction with the Watts Riots of 1965. On August 11, 1965, a fight between a black motorist and two white policemen ignited an explosion of rage that ran for six days, leading to 34 deaths, more than a thousand serious injuries, and fires that destroyed dozens of buildings. Fire fighters trying to put out the blazes were attacked by rock-throwing mobs who seemed determined to let their own neighborhoods burn to ashes. Eventually 4,000 National Guard troops were deployed to support 1,600 police officers enforcing a strict curfew. Historians estimate that at least 30,000 adults participated in the riots. All of this was broadcast every night into American homes using a new innovation, the news helicopter.

In Perlstein's narrative, the Watts Riots was the first in a series of events that fed fear of chaos in "Middle America." Crime was surging, partly but not entirely because the huge baby boom generation was entering the prime mischief years. New drugs spread, and with them drug abuse. Bombs were set off by a dozen kinds of extremists, of both the left and the right; Puerto Rican nationalists bombed the House of Representatives. More riots broke out, especially after the assassination of M.L. King in 1968. Protests against the war led to repeated confrontations between demonstrators and police, and the mass of the public was not on the side of the protesters; a poll taken the day after National Guard soldiers shot four students at Kent State found that 78% of Americans thought the protesters were to blame.

The country seemed to be spinning out of control. The hippies, the yippies and the radicals were not really very numerous, but they got outsized attention both from those excited by the prospect of change and those horrified by what looked like squalor and barbarism. Fear of communism had eased since 1962 but was still a powerful force, and that some on the left embraced Maoism enraged millions. Families broke up over long hair and beards.

One result of all this, says Perlstein, was a new kind of politics in America. Instead of economic issues that divided the workers from the bourgeoisie, elections would now be fought over cultural issues that divided the hippies from the squares. One of the famous events of those years was the Hard Hat Riot in New York, when 200 construction workers attacked anti-war protesters and were joined by a few dozen Wall Street guys in suits; the workers and their bosses were uniting to fight the revolutionaries. Some Americans these days seem to think that our politics of identity and culture are something new, but Perlstein produces dozens of statements from both the left and the right that could have been made today. In fact one is tempted to say that although the issues have changed, the parties and their attitudes toward each other are exactly the same now as they were in 1968.

What makes the events of the 1960s more tragic than those of our own time is the Vietnam War. All the smart people in America knew by 1966 that the war was an unwinnable mess, including Nixon and his top diplomat, Henry Kissinger. It went on because no way could be found for the US to exit without its tail between its legs. Millions of Americans believed that the war was a test of our resolve as crucial, for us and the world, as World War II; millions of others believed it was a crime and a blunder. The division ran through the whole society, including the military; the prosecution of William Calley for the My Lai massacre led to fist fights in officers' clubs. Vietnam was so big, so important, that it made sensible centrism impossible; you were either for the war or against it. To those who supported the war, those who opposed it were traitors; to those who opposed it, its supporters were murderers. Not that politicians didn't try to fudge the issue; Hubert Humphrey ran for president in 1968 with positions so muddled that nobody really knew what he thought, and Nixon ran by proclaiming that we had to fight the war harder to get to peace faster. But the war was one issue that could not be finessed or swept under the rug, and it kept boiling up to upset any attempt at compromise.

So the stage was set for 1972. The Democrat was George McGovern, a midwestern liberal who came out wholeheartedly against the war. McGovern was for women's rights, Civil Rights, and peace. Nixon was for order and the flag. Nixon was a widely despised figure with few real supporters, and key news about the Watergate break-in and his army of dirty tricksters was breaking throughout the campaign. But in an atmosphere of riot, protest, sexual liberation, and rapid social change, order and the flag won easily.

One of the interesting things about Nixonland is that although it is a book about politics, it says very little about political ideas. This was the criticism made by George Will when he reviewed it in 2008; the conservative movement, he said, was rich in ideas, not just some gut reaction to hippiedom. And that is true. But Perlstein, who wrote a whole book about Barry Goldwater, knows this very well; he simply isn't very interested. He feels, as many people feel about the politics of our own time, that ideas don't seem to matter. What matters is emotion, especially the hate and anger that American factions pour out toward each other.

Which brings me to this question: what did the revolutionary years of the late 1960s and early 1970s accomplish? It is easy to argue that they accomplished nothing. After all the immediate result was a landslide for Nixon, whose downfall only set the stage for Ronald Reagan. Electorally the radical spasms of those years were a disaster for Democrats. What's more they spawned or at least intensified the division of the nation along cultural lines that still bedevils us, making some question whether our democracy can survive.

But I don't think that is the whole story. Politics, as someone once said, is downstream from culture. And culturally, the radicalism of the 1960s had gigantic effects. Women's rights, gay rights, environmentalism, sexual liberation, no-fault divorce; these things have moved into the mainstream and become major parts of our world.

This seems, I guess, to be the modern condition: on the one side the lovers of strangeness and change, and the other those who long for stability and order. On one side the mixers who revel in the multicultural and the multiracial, on the other the people only comfortable when everyone around them is the same. And maybe these things are really ancient, going back to two genetic types that must be mixed in every successful population. But if so, the rapid changes of modernity have brought this to a boil, and we are all living with the consequences.

Nixonland is a great place to read about how all this has happened.

Dunnicaer

Behold Dunnicaer, a "sea stack" off the northeast coast of Scotland.

This rock is an island at high tide, and getting up is not so easy even when it is attached to the land, because of the 100-foot-high cliffs (30 m).

Recently some archaeologists from the University of Aberdeen have been digging on top, which required the services of experienced mountaineers to get them and their gear up the cliffs.

The place has long been rumored to be an ancient fortress of the Picts, for two reasons. First, in 1832 some local lads climbed up on top, or said they did, and came back with six Pictish symbol stones.

Nineteenth-century drawing of the stones.

In 1862 the stones were acquired by a local grandee who had them built into his garden at Banchory House, where five of them still remain; these four overlook the tennis court.

Second, a place called Dun Foither appears in the Pictish Annals, which mention that it was besieged by other Picts in 681 and 694 AD. Since the Pictish Dun Foither could easily become Dunnicaer in Scottish, the places might well be the same. But there is a complication, a medieval fortress just a few miles away called Dunnotar Castle. Since Dunnotar is also a plausible Scottish rendering of Dun Foither, some scholars have maintained that it is the place mentioned in the Annals.

But excavations at Dunnotar have failed to produce any evidence of Pictish presence, and Dunnicaer was on top of that inaccessible rock, so the question remained unresolved. But with help from climbing rope and helpful guides, archaeology at Dunnicaer has made great progress. The leaders of the current excavations have just announced that the site was a fortress in Pictish times, radiocarbon dated to between 200 and 400 AD. The excavators think it may have served as a pirate base for raiding Roman Britain. The level area on top of the rock measures only 40 by 65 feet (12x20m), and the site had walls made of a timber frame filled with stone, so this would not have been a very roomy residence.

Much of press surrounding the current excavation has to do with the excavators' theories about the symbol stones:

But I do like the attempt to understand the symbol stones by comparing them to the other European writing systems that appeared around the same time. And how delightful to imagine a Pictish lord and his people living on this rock, crammed together for safety in a very snug little fort, dreaming of Roman riches and fearing Roman reprisals or the attacks of their own jealous kinsmen.

This rock is an island at high tide, and getting up is not so easy even when it is attached to the land, because of the 100-foot-high cliffs (30 m).

Recently some archaeologists from the University of Aberdeen have been digging on top, which required the services of experienced mountaineers to get them and their gear up the cliffs.

The place has long been rumored to be an ancient fortress of the Picts, for two reasons. First, in 1832 some local lads climbed up on top, or said they did, and came back with six Pictish symbol stones.

Nineteenth-century drawing of the stones.

In 1862 the stones were acquired by a local grandee who had them built into his garden at Banchory House, where five of them still remain; these four overlook the tennis court.

Second, a place called Dun Foither appears in the Pictish Annals, which mention that it was besieged by other Picts in 681 and 694 AD. Since the Pictish Dun Foither could easily become Dunnicaer in Scottish, the places might well be the same. But there is a complication, a medieval fortress just a few miles away called Dunnotar Castle. Since Dunnotar is also a plausible Scottish rendering of Dun Foither, some scholars have maintained that it is the place mentioned in the Annals.

But excavations at Dunnotar have failed to produce any evidence of Pictish presence, and Dunnicaer was on top of that inaccessible rock, so the question remained unresolved. But with help from climbing rope and helpful guides, archaeology at Dunnicaer has made great progress. The leaders of the current excavations have just announced that the site was a fortress in Pictish times, radiocarbon dated to between 200 and 400 AD. The excavators think it may have served as a pirate base for raiding Roman Britain. The level area on top of the rock measures only 40 by 65 feet (12x20m), and the site had walls made of a timber frame filled with stone, so this would not have been a very roomy residence.

Much of press surrounding the current excavation has to do with the excavators' theories about the symbol stones:

"In the last few decades, there has been a growing consensus that the symbols on these stones are an early form of language," Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in the United Kingdom and the senior author of the Antiquity paper, said in a statement.But Dunnicaer, which has produced six symbol stones, dates to Roman times, so that seems to rule out a medieval origin for the system.

However, until now, it's been unclear when or how this language developed, with some scholars believing it was invented during the Middle Ages, after the Romans left Britain. . . .

Based on their research, the scientists concluded that the Pictish language was likely developed in the third or fourth century A.D., and it may have been inspired, to a degree, by the Romans, who also used a writing system at the time. However, rather than using Latin (the language of the Romans), the Picts developed a writing style that was quite different from that language, the scientists noted in their study.Which is interesting, but I am still not convinced that the Pictish symbols are a written language at all, because of the lack of repeating phrases. Writing on monuments tends to be full of stock phrases like "X lord of Y" or "A son of B", the sort of thing that has allowed linguists to decipher a few words of Etruscan. But the symbol stones have no such repeated phraseology. If they are writing, they are a different kind of writing than any other system known in Europe. If there is a "consensus," I am not part of it.

The scientists also noted that around the time that the Picts developed their language, a writing system known today as Runes was developed in Scandinavia and parts of Germany. Another system, known as Ogham, emerged in Ireland. . . .

"As with Runes and Ogham, the Pictish symbols were also probably created beyond the frontier in response to Roman literacy," the researchers wrote.

But I do like the attempt to understand the symbol stones by comparing them to the other European writing systems that appeared around the same time. And how delightful to imagine a Pictish lord and his people living on this rock, crammed together for safety in a very snug little fort, dreaming of Roman riches and fearing Roman reprisals or the attacks of their own jealous kinsmen.

Thursday, October 25, 2018

The Impact of the Cultural Revolution

The more I learn about China, the more impressed I am by the awful significance of the Cultural Revolution. Ben Thompson agrees:

COWEN: How bullish are you on India’s tech sector and software development?

THOMPSON: I’m bullish. You know, India — people want to put it in the same bucket as, “Oh, it’s the next China.” The countries are similar in that they’re both very large, but they’re so different.

Probably the most underrated event — I don’t want to say in human history, but in the last hundred years — is the Cultural Revolution in China. And not just that 60, 70 million people were killed, or starved to death, or what it might be, but it really was like a scorched earth for China as a whole. Everything started from scratch. And from an economic perspective, that’s why you can grow for so long — because you’re starting from nothing basically. But the way it impacts culture, generally, and the way business is done.

Taiwan, I think, struggles from having thousands of years of Chinese bureaucracy behind it. Plus they were occupied by Japan for 50 years, so you’ve got that culture on top. Then you have this sclerotic corporate culture that the boss is always right, stay in the office until he goes home, and that sort of thing. It’s unhealthy.

Whereas China — it’s much more bare-knuckled competition and “Figure out the right answer, figure it out quickly.” The competition there is absolutely brutal. It’s brutal in a way I think is hard for people to really comprehend, from the West. And that makes China, makes these companies really something to deal with.

Whereas India did not have something like that. Yes, it had colonialism, but all that is still there, and the effects of that, and the long-term effects of India’s thousands of years of culture. So it makes it much more difficult to wrap things up, to get things done. And that’s always, I think, going to be the case. The way India develops, generally, because they didn’t have a clear-the-decks event like the Cultural Revolution, is always going to be fundamentally different.

And that is by no means a bad thing. I’m not wishing the Cultural Revolution on anyone. I’m just saying it makes the countries really fundamentally different.

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

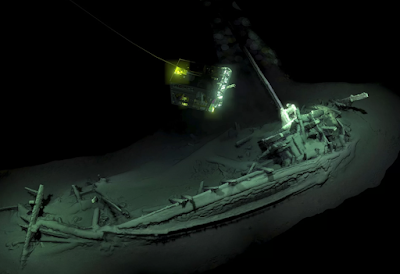

An Intact Shipwreck from 400 BC

Vessel discovered last year on the anoxic floor of the Black Sea, 1.2 miles ( 2 km) below the surface. It has been radiocarbon dated to around 400 BC. Another discovery of the Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project.

The excavators say it resembles this vase painting in the British Museum, but I don't really see it.

The excavators say it resembles this vase painting in the British Museum, but I don't really see it.

Tuesday, October 23, 2018

The Resistance Leader

You have to fight for your freedom and for peace. You have to fight for it every day, to keep it. It’s like a glass boat; it’s easy to break; it’s easy to lose.

–Joachim Ronneberg

Ronneberg was the leader of the Norwegian commandos who destroyed the heavy water plant at Telemark in February, 1943, dealing a blow to the Nazi nuclear program. He died this week at 99.

All nine of the men who were part of that mission had trouble adapting to civilian life after the war:

–Joachim Ronneberg

Ronneberg was the leader of the Norwegian commandos who destroyed the heavy water plant at Telemark in February, 1943, dealing a blow to the Nazi nuclear program. He died this week at 99.

All nine of the men who were part of that mission had trouble adapting to civilian life after the war:

It was very hard on them, almost to a man. They had lived underground under constant threat for years on end, many of them in isolation. So, when the war ended, it was tough on them. They took it in different ways. Some went to the woods and found solace there; Knut Haugland joined the Kon Tiki expedition, lived on a raft, and found peace there. Others found it in drinking; and others never found it. The sacrifices they made and the hardships they endured affected them for the rest of their lives.

Sunday, October 21, 2018

The Spy Who Came Home

Fascinating article by Ben Taub at the New Yorker about Patrick Skinner, a former CIA case office in the Middle East who quit and became a beat cop in his home town of Savannah:

He joined the agency during the early days of America’s war on terror, one of the darkest periods in its history, and spent almost a decade running assets in Afghanistan, Jordan, and Iraq. But over the years he came to believe that counterterrorism was creating more problems than it solved, fuelling illiberalism and hysteria, destroying communities overseas, and diverting attention and resources from essential problems in the United States.Of his time in Afghanistan he says,

Meanwhile, American police forces were adopting some of the militarized tactics that Skinner had seen give rise to insurgencies abroad. “We have to stop treating people like we’re in Fallujah,” he told me. “It doesn’t work. Just look what happened in Fallujah.” In time, he came to believe that the most meaningful application of his training and expertise—the only way to exemplify his beliefs about American security, at home and abroad—was to become a community police officer in Savannah, where he grew up.

“We write these strategic white papers, saying things like ‘Get the local Sunni population on our side,’ ” Skinner said. “Cool. Got it. But, then, if I say, ‘Get the people who live at Thirty-eighth and Bulloch on our side,’ you realize, man, that’s fucking hard—and it’s just a city block. It sounds so stupid when you apply the rhetoric over here. Who’s the leader of the white community in Live Oak neighborhood? Or the poor community?” Skinner shook his head. “ ‘Leader of the Iraqi community.’ What the fuck does that mean?”

Tactical successes are meaningless without a strategy, and it wore on Skinner and other C.I.A. personnel that they could rarely explain how storming Afghan villages made American civilians safer.

They also never understood why the United States leadership apparently believed that the American presence would fix Afghanistan. “We were trying to do nation-building with less information than I get now at police roll call,” Skinner said. Two months into the U.S. invasion, Donald Rumsfeld, the Defense Secretary, revealed in a memo that he didn’t know what languages were spoken in Afghanistan. Each raid broke the country a little more than the previous one. “So we would try harder, which would make it worse,” Skinner said. “And so we’d try even harder, which would make it even worse.”

The assessments of field operatives carried little weight with officials in Washington. “They were telling us, ‘Too many people have died here for us just to leave,’ ” Skinner recalled. “ ‘But we don’t want to give the Taliban a timeline.’ So, forever? Is that what you’re going for? They fucking live there, dude.”

Skinner spent a year in Afghanistan, often under fire from Taliban positions, and returned several times in the next decade. He kept a note pinned to his ballistic vest that read “Tell my wife it was pointless.”

Friday, October 19, 2018

The Tomb of the Infernal Chariot

In October 2003, Italian archaeologists working in the Etruscan necropolis of Pianacce uncovered a remarkable rock-cut tomb they dubbed the Tomb of the Infernal Chariot.

The tomb had been thoroughly looted and only a few artifacts remained, but the pottery dated it to 350 to 300 BC. It consisted of a corridor 60 feet long (19 m) with four niches. The wonder of it is the paintings on the walls. This is the most famous image, the three-headed dragon. In the ancient Mediterranean this was an underworld symbol.

The name comes from this painting, which shows Charon or Charun, the god or demon who transported souls to the land of the dead. You are probably more familiar with the version in which he poles a boat across a river, but the idea that he drives a chariot is also ancient. The painting is about 12 feet long (3.5m).

Detail of the wheel. The chariot is drawn by lions, like that of the earth goddess Cybele.

Hippocampus.

Dolphins. What an extraordinary find.

The tomb had been thoroughly looted and only a few artifacts remained, but the pottery dated it to 350 to 300 BC. It consisted of a corridor 60 feet long (19 m) with four niches. The wonder of it is the paintings on the walls. This is the most famous image, the three-headed dragon. In the ancient Mediterranean this was an underworld symbol.

The name comes from this painting, which shows Charon or Charun, the god or demon who transported souls to the land of the dead. You are probably more familiar with the version in which he poles a boat across a river, but the idea that he drives a chariot is also ancient. The painting is about 12 feet long (3.5m).

Detail of the wheel. The chariot is drawn by lions, like that of the earth goddess Cybele.

Hippocampus.

Dolphins. What an extraordinary find.

Thursday, October 18, 2018

A Buried Viking Ship Discovered

Norwegian archaeologists ran a ground-penetrating radar unit over a burial mound and produced this image of a buried Viking ship:

The Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) said that the archaeologists discovered the anomaly using radar scans of an area in Østfold County. The ship seems to be about 66 feet (20 meters) long and buried about 1.6 feet (50 centimeters) beneath the ground, they said in a statement.

Its keel and floor timbers are intact although precisely how much of the ship is preserved, and when it dates to, are unknown, the archaeologists said.

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

Big Questions in Social Science

Robert Wiblin interviews Tyler Cowen

WIBLIN: What would be your top three questions that you’d love to see get more attention?One of my favorite questions has always been, how do decisions that people feel they are making for personal, idiosyncratic reasons add up to social trends? For example, nobody thinks, I'm not married yet because of a worldwide trend toward later marriage, they think they haven't met the right person yet or what have you. People don't think, I don't want to move out of state because that is no longer popular; they have their own reasons that feel particular to them for wanting to stay close to home. And yet age at marriage is way up and far fewer people move between states. How, exactly, does that work?

COWEN: Well, what’s the single question is hard to say. But in general, the role of what is sometimes called culture. What is culture? How does environment matter? I’m sure you know the twin studies where you have identical twins separated at birth, and they grow up in two separate environments and they seem to turn out more or less the same. That’s suggesting some kinds of environmental differences don’t matter.

But then if you simply look at different countries, people who grow up, say, in Croatia compared to people who grow up in Sweden — they have quite different norms, attitudes, practices. So when you’re controlling the environment that much, surrounding culture matters a great deal. So what are the margins where it matters and doesn’t? What are the mechanisms? That, to me, is one important question.

A question that will become increasingly important is why do face-to-face interactions matter? Why don’t we only interact with people online? Teach them online, have them work for us online. Seems that doesn’t work. You need to meet people.

But what is it? Is it the ability to kind of look them square in the eye in meet space? Is it that you have your peripheral vision picking up other things they do? Is it that subconsciously somehow you’re smelling them or taking in some other kind of input?

What’s really special about face-to-face? How can we measure it? How can we try to recreate that through AR or VR? I think that’s a big frontier question right now. It’d help us boost productivity a lot.

Those would be two examples of issues I think about.

Wednesday, October 10, 2018

Some Puzzles about Birth Rates

While the "birth rate," which measures how many woman have had babies in the past year, has gone down, the "fertility rate," which measures how many babies a woman has over her life time, has gone up from 1.86 in 2006 to 2.07 last year. The explanation for the paradox is that women are having babies when they are older. Anyway, Pew has the numbers here.

One interesting finding is that among women 40-44 who have never been married, a majority have had a child.

One interesting finding is that among women 40-44 who have never been married, a majority have had a child.

Googling Anxiety

Google searches for "Anxiety Help" have quintupled since 2004. Blogger de Pony Sum has the numbers that seem to show this is no fluke; among other things, searches for depression have not gone up anywhere near as much.

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

Fat Bear Week

Unhappy and frustrated about the news? Stressed? Take a break and explore Fat Bear Week, brought to you by Katmai National Park in Alaska. Vote for which bear has gotten the fattest as they gorge themselves in preparation for the winter.

Conservatives Like Realistic Art

From a new paper in the British Journal of Sociology:

Following the UK’s EU referendum in June 2016, there has been considerable interest from scholars in understanding the characteristics that differentiate Leave supporters from Remain supporters. Since Leave supporters score higher on conscientiousness but lower on neuroticism and openness, and given their general proclivity toward conservatism, we hypothesized that preference for realistic art would predict support for Brexit. Data on a large nationally representative sample of the British population were obtained, and preference for realistic art was measured using a four‐item binary choice test. Controlling for a range of personal characteristics, we found that respondents who preferred all four realistic paintings were 15–20 percentage points more likely to support Leave than those who preferred zero or one realistic paintings. This effect was comparable to the difference in support between those with a degree and those with no education, and was robust to controlling for the respondent’s party identity.Via Marginal Revolutions

Monday, October 8, 2018

Throw Open the Treasure Chest

From the Digital Strategy of the Library of Congress:

We will throw open the treasure chest

The Library's content, programs, and expertise are national treasures – we are dedicated to sharing them as broadly as possible. The growth of the Library's digital content, which includes our collections, has increased exponentially every year. We will make that content available and accessible to more people, work carefully to respect the expectations of the Congress and the rights of creators, and support the use of our content in software-enabled research, art, exploration, and learning.

Exponentially grow our collections

The Library will continue to build a universal and enduring source of knowledge and creativity. We will expand our digital acquisitions program; continue our aggressive digitization program, which prioritizes the Library's unique treasures; and improve search and access services that facilitate discovery of materials in both physical and digital formats.Much more at the link. The Library of Congress has indeed become one of the great online repositories of images, maps, and historical texts. I use it every week, and many wonders from its collection have appeared here. (Image is a drawing of a vision by Chief Black Elk, from the LoC.)

How 305 Russian Government Hackers were Exposed

Amusing story:

The public identification this week of more than 300 suspected agents of Russia’s military intelligence service, the GRU, is being dubbed by security analysts the largest intelligence blunder in Russian post-Cold War history.This story doesn't mention that the reason that database is "publicly available" is that corrupt officials within the Russian motor vehicle bureau sold it on the black market. And of course GRU operatives want those special license plates because Russian traffic law is a nightmare of corruption.

And the cause for the bungling comes down, they say, to the simple “human factor” of wanting to avoid traffic fines, including for drunken driving.

Prompted by the midweek disclosure by Dutch and British authorities of the identities of four Russian GRU operators accused of trying to hack the headquarters of the world's chemical weapons watchdog, the investigative journalism consortium Bellingcat subsequently trawled through a publicly available Russian traffic-records database to unearth the names and details of 305 other individuals thought to be working for the Russian intelligence agency.

Passport numbers and, in many cases, mobile telephone numbers were included in the vehicle registrations.

Bellingcat scrutinized the traffic database after one of the four GRU operatives named Thursday by the British and Dutch was found to have registered his Lada car in 2011 using the Moscow address of the GRU barracks housing his cyberespionage unit 26165.

The unit has been accused by Western authorities, including the U.S., of being responsible for a series of cyberattacks and the hacking of computer networks of international anti-doping agencies as well as organizations investigating Russia's use of chemical agents, including the alleged nerve-agent poisoning in the English town of Salisbury earlier this year of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia.

By searching for other vehicles registered to the same address Bellingcat came up with a list of 305 other individuals ranging in age from 27 to 53-years-old.

Sunday, October 7, 2018

Saturday, October 6, 2018

From the Mud of the Amstel River

The City of Amsterdam recently built a new underground line that crosses the Amstel River. During the archaeology for the project, tens of thousands of artifacts were recovered from the bottom of the river. They span the late Middle Ages to the present. They have now set up a web site that displays the objects that were selected for display in the new underground station, and it is pretty cool.

You can view big displays of hundreds of objects.

Or, if one strikes your fancy, click on it and read about it, as I did with this Emperor Charles I hearthstone.

Seventeenth-century padlock. I could spend hours looking at this stuff. In fact, I have.

You can view big displays of hundreds of objects.

Or, if one strikes your fancy, click on it and read about it, as I did with this Emperor Charles I hearthstone.

Seventeenth-century padlock. I could spend hours looking at this stuff. In fact, I have.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)