In the British Museum

Sunday, January 31, 2021

Saturday, January 30, 2021

Meta-Panic Buying

There's a snow storm in our forecast, due tomorrow afternoon. Not a very big storm, mind you, just six inches (15 cm) or so. But my grocery store was completely mobbed already at 7:00 AM today, and the checkers told me it was worse yesterday. There really isn't any reason to rush to the store 48 hours before a storm hits. I think people rushed to the story two days early to beat, not the storm, but the pre-storm panic buying. They are afraid, not of the weather, but of the pre-storm crowds. So, meta-panic buying.

Estonian Folklore and the "King Game"

In the beginning, players of the game are in a circle or in a row, walking or sitting. The player called the ‘King’ is separated from the other players, most frequently located in the center of the circle. The game (as in most older song games) begins with an introductory song from the players that involves most of the verbal part of the game. At first, there is a vocative address to the King, followed by a reproach that he has come at the wrong time, since the current economic situation is worse than the year before or than at any other earlier time. This is escribed in sharp contrast to beer flowing in rivers and wine from springs the year before: there is nothing left now, “in the poor time of spring”. The players also complain that the King is now taking the last of their possessions and assets, mostly described in terms of jewelry. Both statistically and structurally, this seems to be the most crystallized and coherent verbal part of the game.

The game then continues with the King taking away possessions from the players as pledges. This part also features some singing, but it is much less coherent and more variable. Lastly, the players turn to the King and request the return of their possessions. In the associated song, they often explain the origin of their jewelry by stating that these are personal items of emotional significance. At the same time, the players express reluctance to give the King domestic animals in exchange. In the action of the game, the pledges are returned when players perform tasks given by the king.

What the heck is this about?

For one thing, Estonia was ruled by foreign kings and emperors from the 13th century to 1918, most of whom never set foot in Estonia. So it's hard to see why any folklore since that time would focus on an Estonian king.(The Estonian word for king is a German load word, but Siig says the linguists agree it was borrowed a long time ago, certainly before the high middle ages.) Second, the kings in the game don't do anything bureaucratic like collect taxes. They simply show up and demand to be fed and given "gifts." The people reply that this is a terrible time for the king to show up and make demands, since it has been an awful year; if only he had come last year, a time of plenty! The king, undaunted, takes their jewelry and will only return it when they give him what he wants, that is, food and domestic animals. Finally the conflict is resolved when the commoners do tasks assigned by the king.

This sounds, as Siig says, a lot like early medieval kingship. What kings did was travel around to various places and have the local people feed them. And what common people did in response to demands from kings was to plead poverty. (The poverty part of course went on for a long time.)Such a system is known for example from Kievan Rus’ under the name poljud’e. According to Byzantine writers, the Great Prince left Kiev in early winter and travelled through all the lands of the Slavic tribes that held allegiance to him. In the spring, when ice on the Dnieper melted, he returned to Kiev laden with furs and other gifts.

So, says Stiig, maybe the King Game harkens back to the pre-Christian early middle ages. It's an interesting argument, but then I am predisposed to think that a lot of this stuff is thousands of years old.

Kristo Siig, "Kuningamän [‘King Game’]: An Echo of a Prehistoric Ritual of Power in Estonis." The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, University of Helsinki, 2012.

Friday, January 29, 2021

The Armada Maps

Seeing that the Armada had come to a standstill, the English launched an evening attack with eight fireships, unmanned vessels loaded with tar, pitch, and gunpowder. Some of the Spanish captains panicked and put to sea, breaking the formation of the fleet. Because of the strong southwest wind, they were unable to reform and were pushed farther east, beyond the army they were supposed to transport.At dawn the next day the English saw that the Spanish ships were scattered, their formation broken. They pounced, sailing in among the slower Spanish ships and firing broadside after broadside until they ran out of ammunition. They finally caused significant losses to the Spanish, sinking five ships and badly damaging many more.

By the time the English broke off the engagement, the Spanish knew that they had failed. The Dutch were still keeping their barges bottled up, so they still could not reach the army. They knew the English had only sailed off to rearm, and they did not dare try to turn their fleet around and sail back southward into the wind. Their damaged, clumsy vessels would have been picked off one by one. So they decided to keep sailing north, around the north end of Scotland, down the west coast of Ireland and so back to Spain through the Atlantic. But they encountered fierce storms off Ireland and 58 vessels were lost, along with more than 5,000 men.

It was a terrible disaster for the Spanish and the real beginning of the English navy as a feared force on the world's oceans, plus it made Elizabeth I one of England's most beloved sovereigns and may have contributed to the remarkable creative confidence that marked England over the next generation.Thursday, January 28, 2021

Links 29 January 2021

Rod Dreher tries to quit Ambien.

The Great 78 Project is digitizing old 78 rpm records. Project site, article at Atlas Obscura.

Short video of protesters in Moscow pelting riot police with snowballs.

The dream of the reusable space plane lives on.

The serial killer who lived in the same building as his victims, knew them, ran errands for them. Another example of how wrong we are to fear distant strangers more than those we live with. (NY Times)

Kevin Drum says America is in Better Shape than Everyone Seems to Think, with data to back it up.

Six-foot-long carnivorous worms lived in burrows under the Miocene ocean.

The Arizona Republican Party censures three prominent members who criticized Trump. (NY Times)

In surveys, 15 to 20% of Americans think political violence is at least "a little bit justified;" the number does not vary much between the parties but varies a lot depending on how aggressive people are in general.

Immigrants to the US are so important at the higher levels of math and science that any slowdown in US immigration directly reduces "global knowledge production," or so these these guys say.

The humor of American Jewish philosopher Sidney Morgenbesser.

Everyone on TikTok is so oppressed it makes me weep.

The Navy Seals trained him to recognize disinformation, but he still ended up believing in right-wing conspiracy theories and taking part in the Capitol riot. (New York Times)

Twitter thread on Leo Strauss, who thought past philosophers often disguised their real views out of fear of persecution; before cancel culture there was being hanged by the king or burned by the church.

What went down in a QAnon chat room over the month of January. (New York Times)

In the 18th and 19th centuries, lotteries were popular with slaves, who thus purchased a small chance to win their freedom. Denmark Vessey, later famous for leading a slave revolt in Charleston, South Carolina, won his freedom that way. Interesting entry point for thinking about the place of lotteries in our society.

I see that the Wolf Full Moon is back. Sigh.

Thomas Edsall on white Christian nationalism in the US, (New York Times)

The ongoing dispute over whether coconut milk is made with forced monkey labor.

The ratings are down at Fox News, and some think this is a sign of a long-term problem for them: with Trump's core followers going full-bore for conspiracy, it may be all but impossible to retain them as viewers while maintaining any semblance of being a news channel.

Wednesday, January 27, 2021

The Slave Quarter at Oak Hill Plantation, Pittsylvania County, Virginia

The descendants of Hairston slaves still keep in touch, and back in the 1990s a researcher was able to interview several old folks who preserved family stories about slave life:

Daniel Hairston was an elderly descendant of Oak Hill slaves visited by the author. Hairston was born in 1920 with three of his grandparents having been slaves. Both his grandfathers, Gus Hairston and Jube Adams, had been slaves at Oak Hill. Gus used to cut ice on the river for the icehouse at Oak Hill. Daniel recounts a story of Gus working in the garden and getting himself some butter that he shouldn’t have. He was “whupped” for an unrelated offense causing the butter to fall out from under his hat where he’d hidden it. This discovery caused him to be beaten again. Daniel relates that his grandfather told it as a joke but it was a reminder that they had to take whatever was dished out just to survive.

Daniel recalled another story of how Oak Hill’s enslaved people would sometimes gather at night to kill a hog and take it off into the woods to cook. They would use fence rails for firewood and burn up all of the inedible remains to hide them before dawn. Similarly, if the enslaved population wished to worship together they would gather in the woods at night, placing a large cauldron upside down to supposedly muffle the sound.

A great aunt of Daniel’s who was enslaved at Oak Hill was once slapped in the face by “Ol’ Miss,” or the wife of the plantation owner. His great aunt was so enraged that she stuck her long fingernails into the mistress’s satin dress, tearing it. The aunt was so terrified at what she’d done that she left the plantation and went into hiding for two years. The oral history indicates that when she returned she was left unpunished for her absence. This tale was passed down through the family to show that the great aunt’s faith in God gave her the strength to return home and helped her evade punishment.

The last story is a very interesting example of a common practice in slave societies. Enslaved people sometimes just left after fights or other incidents and stayed away until they were given assurances that they would be welcomed back. Only a few "runaways" tried to make it to freedom; many more hung around the neighborhood until they were caught or made arrangements for their return, and some were just trying to visit spouses, children, or other relations from whom they had been separated.

The building had four rooms, each with a fireplace. The archaeologists had time to dig two excavation units. The position of the first one was obvious, on top of this feature, a brick-lined pit measuring 5x5 feet (1.5x1.5m).Which after excavation looked like this. It has been bisected, as we say, and half excavated. This was a storage pit or root cellar. North American slaves loved these and dug them in most of their homes in the 1720-1860 period. In-floor storage pits are common around the world, including among English settlers in North America, and among many Native Americans. The habit of putting a pit in front of the fireplace seems to come from England. But few people have been as invested in the practice as enslaved North Americans. Some slave quarters I have seen had three or four pits. (They had boards over them most of the time.) Some archaeologists have speculated that this was done to hide extra food or stolen items, but honestly, these were not very secret, and the root cellar is the first place an overseer looking for a stolen item would search. So it may be better to think of these as private rather than secret places. Things one didn't necessarily want hanging in the open could be placed in the pit, giving the people who lived in these small homes, always under the owner's eye, some small measure of control over their lives.The visible brick feature in the first room was a stroke of luck; most features are nothing like that obvious. In the other room they investigated, the archaeologists troweled the dust layer off the floor. They were then able to see this stain; this is what most pit features look like when they are first exposed. They are usually darker than the surrounding subsoil, and they hold water better, because of the extra organic matter.See? Archaeology isn't so hard.That pit looked like this after excavation. Most likely there is a similar pit in each room, so that each family had one.Now we get to the hard part of archaeology: how, why, and when were these holes filled in? Usually we have no idea. The soil in these holes did not wash in, because that would have damaged the unmortared brick lining. Someone must have filled them, after they were no longer in use. From the artifacts found in them we can guess that was years before the building was abandoned, probably before 1850.

Archaeologists expect, or hope, that the artifacts in the pit were used by the people who lived in the house. Usually, we are right, but not always. Sometimes people fill in holes with dirt from somewhere else. An old archaeologist I knew in Delaware many years ago swore to me that he once saw a guy back a pickup truck up to an old cellar hole and shovel in a truckload of trash, then drive away. So if you ever want to flummox a young archaeologist nervously reading a paper, ask him or her where the dirt in the hole came from. (There is even a name for the study of where the dirt came from, Taphonomy. So if you really wanted to be an obnoxious questioner you could ask, "I wonder if you could elucidate the taphonomic processes at work here for me.")

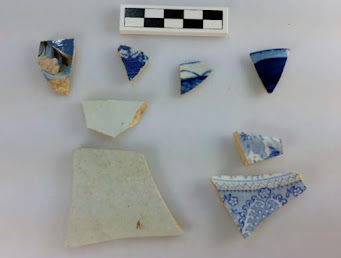

But placing our hope in the odds, and assuming this stuff came from the slave quarter, what was found in these pits? All sorts of things! Like, a dozen glass beads in different colors, a frying pan handle, a bone-handled fork, tobacco pipe fragments, nails, bottle and window glass, mother of pearl and glass buttons. And this mocha-decorated Pearlware, made between 1790 and 1840. The mocha glaze was made with urine, one of the many, many industrial uses for piss that Europeans came up with.Tuesday, January 26, 2021

York through the Eyes of Thomas and Eleanor

St. Olave was of course a Norwegian king, and the presence of St. Olave's Church reminds us that York was once Jorvik, a Viking town. It was in Jorvik that Egil Skallagrimson saved his life by composing, in one night, the Viking world's most famous poem of praise, a gift so magnificent that Jarl Eirik Bloodaxe had no choice but to spare his enemy Egil's life in return. In the 1970s a major excavation was carried out at Coppergate in York, exposing more than a dozen 10th century houses and recovering tens of thousands of artifacts from Jorvik. The results are now interpreted in both a more or less normal museum (although holographic ghosts pop up from time to time to lecture you) and a "Viking Experience" where you can ride through a recreation of the town.