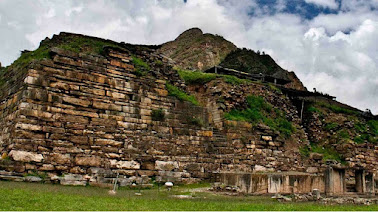

The Falcon Gateway, the entrance to the complex, and a close-up view of the carvings.One thing we know about the rituals at Chavín is that they involved drugs. Specifically, depictions of the San Pedro cactus, the source of mescaline, have been found in carvings and other art at the site. Drug paraphenalia such as snuff dishes and snorting tubles have also been found. There's another cactus behind the tail of this charming jaguar. Interesting that jaguars, anacondas, and harpy eagles are prominent in the art of Chavín, all of them creatures of the Amazon lowlands not found the Andes.One of the interesting kinds of work going on at Chavín de Huántar is archaeo-acoustics. The site is in a valley with interesting echoes, and conch shell trumpets have been found at the site. (These are still used in Andean music, under the name of pututus.) This relief from Chavin shows an important person with a conch shell in its hand. Anthropolgists have been blowing the trumpets and creating other sounds at locations around the site, studying the acoustic effects. (Video here; you can hear how a conch shell sounds when played by an expert.) Their publications are choked with post-modern anthropology speak, but so far as I can tell they think the site was chosen, and the temple constructed, with acoustic effects in mind.

The site has been back in the news because archaeologists are exploring a new set of tunnels under the citadel. These were actually discovered in 2019, but a bureaucratic Catch-22 arose: the tunnels were too narrow to allow the required spacing for Covid-19, so people could not go in together, and safety rules forbade anyone going in alone. So exploration had to wait until recently.

Arnthropologist John Rick of Stanford, involved in the recent work, explains what he thinks went on in the tunnels:Lost in a labyrinth of underground tunnels lit by sunlight, adorned with stone carvings that appear to roar at passers-by, water that rushed up to meet them, visitors would have been completely disoriented by the experience. “It was a convincing system,” says Rick. “And it pushed the innovation of advanced technology. They were using hydraulics, acoustics, mirrors, psychoactive drugs. They made water dance and sing by its motion through canals. The creators of the temple were pushing their scientific understanding forwards. This is a way of showing off but in a very serious – cultic – sense. . . . The drugs fit hand in glove with what was going on at Chavin. They were credibility drugs, they’re not the most extreme where you’re completely out of your world – the users weren’t catatonic. You live with them and become more impressionable. They’re ideal for this system.”So the tunnels, the drugs, the soundscape, and the water effects, as well as other elements that have disappeared such as costumes, dancing, chanting, and so on, were deployed to create experiences for cult members. Like guided shamanism. In the modern world this takes two forms: the initiate can be led to see the world and its god as society understands them; or the vision can be more personal, directed toward finding one's own spirit guide or understanding one's own spiritual path. There is no reason to doubt that both paths existed 3,000 years ago as well.

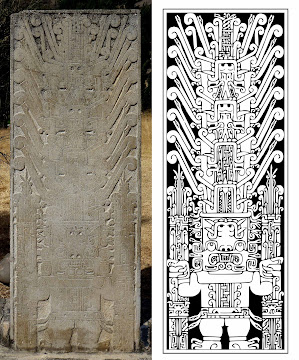

One reason to think that this was a cult for initiates is the art. It is deliberately complex and obscure, with many references it has taken archaeologists decades to unravel and some we still don't understand. Above is the Raimondi Stele, thought to come from Chavin. It depicts the Staff God, who would be prominent in South American iconography down to the conquest.

Nose ornament from Chavín de Huántar

Imagine the effect of all this on newcomers. Climbing to the remote site, they are greeted with music and chanting that echoes off the canyon walls. Passing through the great stone gateway with its spectaular carvings they enter a world far removed from their villages. They are offered cups of a sacred beverage to drink, further heightening their senses. Dancers perform in garish costumes. Songs or recited poems tell ancient, obscure stories that hint at deeper truths about humanity and the universe.

Their minds whirling with all of this, they see the initiates led off to participate in secret rituals underground. Would they not be curious? Would not some of them willingly pay to be taken deeper into the cult? Would not control of all this make the leading priests powerful people?It's a fascinating site, and an intriguing model for understanding the rise of powerful temple hierarchies across the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment