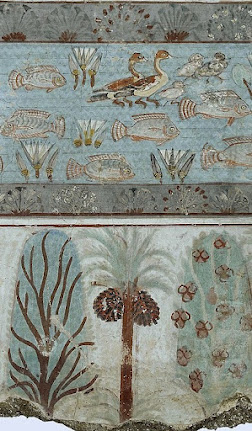

The garden of the Egyptian scribe Nebamun, from the wall of his tomb, c. 1350 BC

The archaeological record of the Faroe Islands begins around 850 AD, with the arrival of the Vikings. But study of lake sediments reveals that sheep arrived around 500 AD, and presumably somebody must have brought them.

Lovely photographs of the Faroes by Lazar Gintchin.

Polar bears took over an abandoned settlement in the Russian arctic, and Dmitry Kokh has amazing pictures.

Investigation of red light cameras in Chicago finds that they give out many more tickets in black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Racism? Something to do with the geometry of poor neighborhoods? Or just a difference in behavior? One complaint I think is legitimate is that the fines ($100 or so) are trivial for well-off people but onerous for the poor. But I think the solution often suggested, making them a percentage of your income, turns what it supposed to be a simple, cheap safety measure into complicated bureaucratic problem.

In an interesting essay at Harper's, Meghan O’Gieblyn ponders the role of routine in her life, and ours.

The news from 9th-century Peru: during the Wari Empire, people at a settlement now called Quilcapampa held communal feasts at which they drink a lot of chicha, a beer-like liquid made from the molle tree, laced with the hallucinogen vilca seeds. The excavators say the ruling elite provided these feasts as a means of maintaining control, but I'm not sure getting everyone roaring drunk is always a good way to keep them under control.

Broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), a grain crop from East Asia, was grown in Iraq by 1100 BC. The archaeologists who published this make it out to be a surprise, but it seems to me one thing we know about early farmers is that they were always on the lookout for new plants and shared them widely. Think how quickly potatoes were taken up in Europe, and hot peppers around the world.

The underground town of Nushabad, Iran; to me the most impressive thing is that it was somehow completely forgotten for centuries.

New study argues that multiple sclerosis is triggered by viral infection, in particular by the Epstein-Barr virus.

DNA analysis reveals that the animals that pulled Ancient Mesopotamian war wagons, called kunga in our sources, were infertile crosses between domesticated donkeys and wild Syrian asses.

Looking around for something on the political fight over wolf and bear hunting in Montana and Idaho, I found this NY Times piece, which says "predators are part of the culture wars," and this ungated piece at Vox. Some people just hate wild predators and like to blame them for things, possibly because shooting them restores a sense of control. As a rancher you can't do much about Federal range rules or beef prices or the weather, but you can get your gun and defend your land. But there is no evidence that the 1,200 wolves in Montana are having any impact on either ranchers' profits or elk and deer populations.

More "specimen cabinets" by Steffen Dam.

The mysterious habit of concealing shoes in buildings – in foundations, behind walls, under floors, in attics – which goes back at least to the Middle Ages and continued well into the 20th century. Thousands of cases are known.

A list of contemporary "heresies."

Rasmussen poll finds large numbers of Democrats favor harsh penalties for people who refuse to get vaccinated or question the efficacy of Covid vaccines on social media. I suspect most respondents were venting their anger rather than really advocating prison for the unvaccinated, but they're not displaying much tolerance.

The Biden administration calls for an extra $650 million a year to be spent on controlled burns and forest thinning in the west to better control forest fires. (NY Times)

Lots of chatter these days about huge batteries to help out utility grids, but the best way to store a lot of energy is still pumping water uphill: one project being built in Australia will have more storage capacity (350,000 megawatt hours) than all the utility-scale batteries in existence.

Brown Windsor Soup, allegedly a famous lowlight of English cooking, never really existed until after it became a widespread joke.

Jonathan Rauch and Peter Wehner argue that while the Left in America is bad, the Right is worse and much more dangerous. (New York Times)

Defense vlogger Binkov has a 20-minute video up on how drones will change warfare. He thinks they will only further advantage the richer, better-armed side and will not help weaker forces (terrorists, insurgents) overcome stronger governments.

CIA report says they have no evidence linking "Havana Syndrome", the mysterious ailments suffered by some US diplomats, to "state actor involvement." Sick people used to blame demons or witches, but now they blame microwave attacks.

Politics as a health threat: "the findings from the survey suggest that somewhere between a fifth and a third of adults—roughly 50 to 85 million people—blame politics for causing fatigue, lost sleep, feelings of anger, loss of temper, as well as triggering compulsive behaviors."

The University of Michigan has fired its president for an entirely consensual affair with a subordinate. Ok, he was the president, and it was against the rules, so maybe we should expect him to abide by the rules he is in charge of enforcing. But this bugs me: "Schlissel’s conduct was 'particularly egregious' because he had taken a public position against sexual harassment, the board said." (New York Times) Why can't you be against sexual harassment and for consensual relationships between adults? Why is love, which this appears to be, an offense against the smooth running of institutions so offensive it must be stamped out, the perpetrators dismissed?