The Outer Hebrides are a chain of wind-swept islands that stretch for 130 miles (210 km) off the northwest coast of Scotland. Fifteen of the islands are inhabited, with a total population of about 27,000, and there are dozens of uninhabited islands. A majority of the inhabitants speak Gaelic. The main islands are Barra, North and South Uist, Harris, and Lewis. Yes, that's a picture of Scotland, to be specific the Island of Lewis, with sweeping sand beaches and turquoise water. Too bad it's probably freezing.

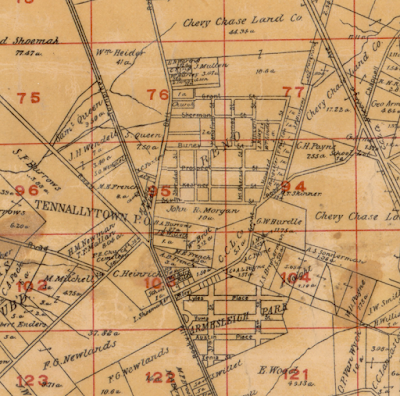

Map showing the shape of the islands, and how exposed they are to Atlantic swells and storms. The motto of the local tourism board is "Experience Life on the Edge." The oldest evidence of human presence on the islands dates to Mesolithic times, around 6500 BC, which is like the rest of Scotland. To me this shows how restless and adventurous Mesolithic hunter-gatherers could be; they just kept going until the ocean stopped them.

The islands are a famous spot for walking, if you don't mind rough weather. You are warned that

Some of terrain is as rugged as anywhere else in Scotland and the weather here in the Outer Hebrides is famously changeable – very often, you will experience all four seasons in one day.

The picture shows a view from the Clisham Horseshoe, a 9-mile (15 km) route on Harris which

this web site says is one of the ten best hikes in the British Isles.

There is a trail that runs the length of the island chain, called the

Hebridean Way: 156 miles (250 km), 10 islands, 6 causeways and 2 ferries. There is also a biking trail that runs the same distance along a somewhat different route.

The Hebridean Way begins on Vatersay, a small island at the southern end of the chain. On Vatersay it passes several bogs, like this one full of Bog Bean. Besides the changeable weather the islands are also famous for midges.

On Vatersay you pass by the first evidence of the ancient past, stone round house foundations dating to the Iron Age.

The trail crosses a causeway to Barra and passes by Kisimul Castle, built in the 1400s. From the 700s to after 1200 the island was dominated by Vikings, sometimes part of the Kingdom of Mann. In the 1200s the kings of Scotland got control of the area, and it later became part of the Lordship of the Isles. The MacDonalds granted this stronghold to the MacNeils, who held it through the 15th and 16th centuries. They were great pirates and often preyed on English shipping, especially in the time of Elizabeth I, when they supported the Spanish cause in the war of the Spanish Armada.

From Barra you catch a ferry to Eriskay and then cross a causeway to South Uist. Here the scenery is spectacular, with both high hills and sweeping beaches.

Historic sites abound, from ruined castles and monasteries to standing stones to the Bronze Age Site of Cladh Hallan, where strange mummies were found composed of parts from several different people. In the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries the islands were troubled by murderous clan warfare involving characters with names like Black Archibald, Donald the Hunchback, Donald Gorm and Donald Gormson. These feuding islanders caused so much trouble that at one point Mary of Guise, Regent for Mary Queen of Scots while she was in prison, issued "Letters of Fire and Sword" to two Scottish Earls, calling on them to exterminate all the clan leaders of the Uists. They endured, though, until they were finally put down in the aftermath of Bonnie Prince Charlie's

1745 rebellion. Over the century after that defeat thousands of islanders left, some heading to Glasgow, others to North America or Australia.

One crosses by causeway to North Uist, and then by ferry to Harris. Harris is the most mountainous part of the Hebrides, with thirty hills rising to over 1,000 feet (300 meters).

Harris is best known as the place where Harris Tweed is made. These days the wool comes from the mainland, but it is still prepared, dyed, and woven on Harris using traditional methods. The dyes are made locally from plants that include lichen, seaweed, nettle, bog myrtle and iris.

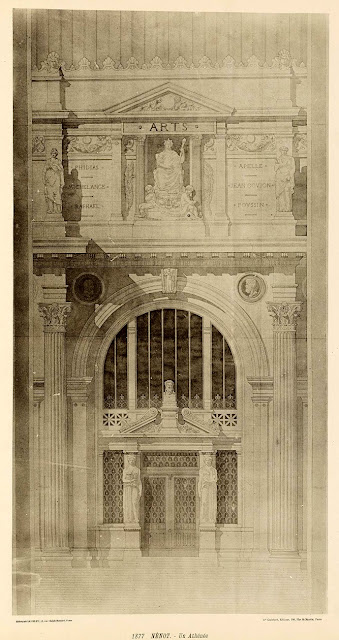

The most famous church in the islands is St. Clement's in Rodel.

The outside is nothing special but the interior includes some wonderful tombs, like this one of Alasdair MacLeod, from 1528.

Detail. The figure at the top left is the Virgin Mary, and next to her, holding a skull, is St Clement. To the right is a galley under sail. St Michael and the Devil weigh the souls of the dead, next to the Latin inscription which translates as: "This tomb was prepared by Lord Alexander, son of William MacLeod, Lord of Dunvegan, in the year of our Lord 1528".

Beyond Harris is Lewis, actually part of the same island but connected only by a narrow spit. Lewis is geologically quite different, low and flat rather than hilly.

Lewis is home to yet more wonderful monuments, most famously the standing stones of Calanais.

There is a wonderful Pictish

broch from the first century AD, known as Dun Carloway.

At Garenin you can visit a small village of restored "Blackhouses", as the traditional stone houses of the islands are called.

The Hebridean Way takes you to Stornaway, with 8,000 people by far the largest town in the islands. Here many people stop and catch the ferry back to the mainland.

Others continue on to the Butt of Lewis at the islands' far northern tip, where there is a famous lighthouse. You have come a long way by this point, however you are travelling, but you have seen wonderful things.