Thursday, September 30, 2021

US Covid-19 Case Rate vs. Population Density

Religion and Politics in the US

Jupiter's Red Spot Has Shrunk a Lot

Wednesday, September 29, 2021

Affective Polarization and the Turn Against Democracy

Most of Thomas Edsall's NY Times columns amount to conversations with social scientists about some major issue in the news. He reads their papers, then calls them or emails them for comment. I think it's a great format, and the most recent installment is very interesting. Edsall has been asking people about "affective polarization," which means that voting behavior is driven mostly by hatred and distrust of people in the other party. Everyone agrees that this has increased in the US, and some say it is increasing worldwide.

Edsall's questions have to do with how much is explained by affective polarization. Edsall starts from a major paper that appeared in Science last year, arguing that it is driving our political disfunction:

The political sectarianism of the public incentivizes politicians to adopt antidemocratic tactics when pursuing electoral or political victories. A recent experiment shows that, today, a majority-party candidate in most U.S. House districts — Democrat or Republican — could get elected despite openly violating democratic principles like electoral fairness, checks and balances, or civil liberties. Voters’ decisions to support such a candidate may seem sensible if they believe the harm to democracy from any such decision is small while the consequences of having the vile opposition win the election are catastrophic.

Following this argument, it would seem that affective polarization is driving things like laws limiting ballot access, election "audits", and violent attempts to undo election results.

But others say, not so fast; they think that while affective polarization exists and is a problem, it doesn't seem to explain anti-democratic feelings or practices. They have done experiments to show that the degree of affective polarization is relatively easy to manipulate up or down, but they find that this has no effect on attitudes toward voting restrictions etc., or especially on violence. Support for political violence, which is very much a minority attitude, seems oddly disengaged from hatred of the other party.

(This would fit with a theory I have defended here in other contexts, that violence is its own thing, feeding mainly on itself rather than on other sorts of conflict.)

In response to these findings, the scientists Edsall queries have four sorts of responses:

- This type of research is irrelevant, and in the real world affective polarization and anti-democratic views absolutely do go together;

- We have no idea what is driving the turn against democracy, and this is worrying;

- The explanation is elite behavior, especially that of Republican leaders, and Americans are turning against elections because Trump and his allies keep attacking election results and vaguely advocating what a Fascist would call "direct action";

- It must have something to do with race and racism, because, I mean, what about American politics doesn't have something to do with race and racism?

I think that as far as the events of the past year go, 3) is mostly correct; most of the anti-democratic acts we have seen have been Republican, and that this absolutely goes back to Trump and his friends. Which means that at some level 4) is also involved.

But this doesn't explain everything. There is also an angry left, embodied by anarchists in Portland but also in the form of various people I know. Polls show that young people across the western world are much less likely to call democracy "essential", and in one Pew survey 46% of young Americans said they would prefer government by experts to democracy.

I think that while Trump & Co. are leading the assault on democracy, they only have support because of a widespread sense that democracy is failing us. In fact I think widespread anger about systemic failure explains how Trump ended up in the White House in the first place. There are a range of issues –immigration and industrial decline are prominent on the right, racism and climate change on the left – that leave many Americans feeling like their government has turned against them. Since elections seem to produce no meaningful change in how these issues are dealt with, the temptation to try other options rises.

In the short term what is required is to oppose the Trump crowd and defend elections against their machinations. The long term issues may prove much harder to resolve.

Tuesday, September 28, 2021

Dostoevsky Ponders the Fate of Humanity Amidst Riches

Notes from the Underground, Chapter VIII:

In short, one may say anything about the history of the world—anything that might enter the most disordered imagination. The only thing one can't say is that it's rational. The very word sticks in one's throat. . . .

Now I ask you: what can be expected of man since he is a being endowed with strange qualities?

Shower upon him every earthly blessing, drown him in a sea of happiness, so that nothing but bubbles of bliss can be seen on the surface; give him economic prosperity, such that he should have nothing else to do but sleep, eat cakes and busy himself with the continuation of his species, and even then out of sheer ingratitude, sheer spite, man would play you some nasty trick. He would even risk his cakes and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive good sense his fatal fantastic element. It is just his fantastic dreams, his vulgar folly that he will desire to retain, simply in order to prove to himself--as though that were so necessary-- that men still are men and not the keys of a piano, which the laws of nature threaten to control so completely that soon one will be able to desire nothing but by the calendar.

And that is not all: even if man really were nothing but a piano-key, even if this were proved to him by natural science and mathematics, even then he would not become reasonable, but would purposely do something perverse out of simple ingratitude, simply to gain his point. And if he does not find means he will contrive destruction and chaos, will contrive sufferings of all sorts, only to gain his point! He will launch a curse upon the world, and as only man can curse (it is his privilege, the primary distinction between him and other animals), may be by his curse alone he will attain his object--that is, convince himself that he is a man and not a piano-key! If you say that all this, too, can be calculated and tabulated--chaos and darkness and curses, so that the mere possibility of calculating it all beforehand would stop it all, and reason would reassert itself, then man would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason and gain his point! I believe in it, I answer for it, for the whole work of man really seems to consist in nothing but proving to himself every minute that he is a man and not a piano-key! It may be at the cost of his skin, it may be by cannibalism! And this being so, can one help being tempted to rejoice that it has not yet come off, and that desire still depends on something we don't know?

Ever since modernity opened up the prospect of a world without want, people have been asking what such a world would be like. A great many of them have agreed with Dostoyevsky: that we would blow up the whole thing rather than let social engineers contrive our happiness.

I am not sure how true that is, but it is certainly true in part. Our relationship to peace and prosperity is complicated and sometimes perverse.

If you consider science fiction, you find that the optimistic kind is mostly about exploration: sailing between stars, these authors suggest, we will find wonders and horrors enough to keep us from blowing our civilization to pieces. Staying on earth with replicators and holodecks is too awful to contemplate.

You might consider Asimov's Foundation series a response to this passage; what if our learning were so great that we could really predict our future? That we could even predict when we would rebel against the predictions and try to overthrow them? Because we absolutely would.

One reason I sometimes find my fellow human baffling is that I believe, very deeply, that we are not capable of perfection. I hope for a better world; I believe in working for a better world. But I find the idea of perfection both impossible and intolerable. Whenever anyone says something like G.W. Bush's "we will rid the world of evil" or a call to "eliminate sexism" I shudder. But "Let's strive to keep our problems within reasonable bounds" doesn't make much of a battle cry.

I have an acquaintance who is a revolutionary socialist. He seems, so far as I can tell, to be a mostly reasonable person. He has acknowledged, in response to my prodding, that past revolutions have at best achieved modest gains in welfare at very high cost. He admits that many revolutions have made the world worse. And yet he continues to believe we must have another, because he finds the current state of the world intolerable. He finds it unbearable that anyone goes hungry in a world with billionaires, that any woman anywhere is kept from her dreams by male oppression, that any child is abused, that any species be driven to extinction. Since our current system cannot fix these problems, we must have a revolution, and if that fails we must keep having them until the suffering is over.

Talking to him makes me feel callous and cruel. What is my excuse for not being constantly angry about the state of the world, for not devoting my every waking moment to improving it? But I have to admit that I do not find the dream of utopia appealing at any level. Even if we could achieve it, which I do not believe we could, we would just blow it up and start over again, because struggling is what we do.

More Myths about Rotten Food: African American Spice

This is NOT TRUE.

My old post about pepper and rotten food in Medieval Europe has logged several hundred page views, so perhaps I have made a small contribution to fighting that nonsense. So I'm going to wade right in and try to fight this one as well. Let's recap a couple of things:- It is not possible to hide the taste of rotten meat.

- Even if you could, rotten meat doesn't just taste bad, it is poisonous. Adding spice would probably just make you sicker.

- We know quite a lot about the diets of enslaved people in the Caribbean and the American South, from a variety of sources – plantation accounts, agricultural journals, narratives by enslaved people themselves – and rotten meat doesn't feature much.

I'm not saying that nobody anywhere wasn't ever hungry enough to try eating rotten meat; no doubt that happened all the time. They got sick. If they were weak from hunger they might have died. Spices wouldn't have helped them.

I'm also not saying that slaves were always well fed or that their diets did not contribute to the evolution of African American cooking. Not being given enough food was a standard complaint of slaves, and a lot of "Soul Food" was about turning the cuts of meat that planters didn't want for themselves into palatable meals. The bones I excavated at the Bruin Slave Jail in Alexandria, Virginia were mostly the heads and feet of cows and pigs. There is a lot of nutrition in those parts of the animal, but they weren't much sought after, so they were cheap. That deposit also included thousands of oyster shells, which, again, were cheap, at least at certain times of the year. Oysters spoil quickly so it is quite possible that slaves who ate them sometimes got sick, but then that happened to white people, too.And also what this commenter said. Heavily salted meat was very common in the Americas, for white people as well as black, because salt was cheap and so it was the simplest way to preserve meat for later. Also, heavily spiced and salted food is a West African tradition, and by eating that way enslaved people were maintaining their own culture, not just trying to survive on rotten flesh.There is an interesting worldwide association between heavily spiced food and poverty. The most refined and expensive cooking avoids the heavy use of hot peppers or horseradish in all the cultures I know anything about, and in many places the poor have a special fondness for spice. I suppose this is because heavily spicing your food is an inexpensive way to make your life a little more interesting, although various neo-Freudian explanations also come to mind.

But there really isn't any reason to trash-talk Soul Food, any more than there is to trash-talk the Blues. Yes, they emerged from a culture of poverty and oppression. But they have a value that transcends the sadness of their origins.

Enslaved black people ate spicy food because they liked it. Let's not retroactively ruin the pleasures they found amidst their toils.

Monday, September 27, 2021

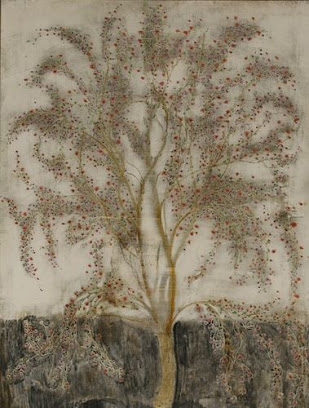

Mamma Andersson

Her paintings are mysterious, enigmatic, but still kind of everyday life-ish. They show people in empty rooms; she also paints forests and landscapes where there’s always something slightly threatening, but you don’t quite know what it is. There’s an apocalyptic feeling in some of them, but they’re very beautiful too.

Swannery, 2019.

Shoreline, 2021Paleogenetics and Etruscan Origins

Now there is paleogenetic data that bears on the question:

The origin, development, and legacy of the enigmatic Etruscan civilization from the central region of the Italian peninsula known as Etruria have been debated for centuries. Here we report a genomic time transect of 82 individuals spanning almost two millennia (800 BCE to 1000 CE) across Etruria and southern Italy. During the Iron Age, we detect a component of Indo-European–associated steppe ancestry and the lack of recent Anatolian-related admixture among the putative non–Indo-European–speaking Etruscans. Despite comprising diverse individuals of central European, northern African, and Near Eastern ancestry, the local gene pool is largely maintained across the first millennium BCE. This drastically changes during the Roman Imperial period where we report an abrupt population-wide shift to ~50% admixture with eastern Mediterranean ancestry. Last, we identify northern European components appearing in central Italy during the Early Middle Ages, which thus formed the genetic landscape of present-day Italian populations.

Of the 48 people who lived BC, 40 were perfectly standard western Mediterranean types. So the Anatolian migration theory is out. They had a bit of steppes ancestry, so they were not isolated from the Indo-European invasion that changed the other languages of the peninsula, but for whatever reason they kept their old language while others did not.

More striking is the evidence of major immigration from the eastern Mediterranean during the Roman Empire. This was also true at Rome, but not nearly to this extent; I have to think that this is a sampling problem, and that immigrants did not really make up half the Tuscan population.

And, again as at Rome, there is clear evidence of invaders from the north (Ostrogoths, Lombards, Franks) during the early Middle Ages.

I am just loving that I can experience all this genetic data coming in to answer age-old questions.

The Moorish Sovereign Citizens

The Sovereign Citizen movement originated among white supremacists in the 1970s and made the news several times in the 90s. The central belief is that its members are independent states unto themselves, not bound by the laws of the US or any other nation. I have always found it an interesting thought exercise. What argument can one use against such people except force? We have police and an army, and you don't, so buzz off. I can't think of anything else one could say to them.

Since everyone in the US has been so focused on racial divides lately, it has been an interesting to watch as this peculiar ideology spreads among black radicals.

Known as the Moorish sovereign citizen movement, and loosely based around a theory that Black people are foreign citizens bound only by arcane legal systems, it encourages followers to violate existent laws in the name of empowerment. Experts say it lures marginalized people to its ranks with the false promise that they are above the law. . . .You have to love that detail about maritime law. What?

This past summer the Moorish movement exploded into public view, after Ms. Little posted viral TikTok accounts of her ordeal and when the police pulled over members of a militant offshoot of the group on a Massachusetts highway. That subgroup, known as Rise of the Moors, engaged in a standoff with the police for more than nine hours, claiming that as sovereign citizens, law enforcement had no authority to stop them. No one was injured; 11 people were arrested and charged with unlawful possession of firearms and ammunition, among other offenses.

Increasingly, across the country sovereign citizens have clashed with the authorities, tied up resources and frazzled lives in their insistence that laws, such as the requirement to pay taxes, obey speed limits and even obtain, say, a license for a pet dog, do not apply to them.

People who claim to be Moorish sovereign citizens believe they are bound mainly by maritime law, not the law of the places where they live, said Mellie Ligon, a lawyer and author of a study of their impact on the judicial system in the Emory International Law Review. (NY Times)

The major nuisance caused by these folks lately has been claiming property as their own, based on deeds and titles they issue to themselves. Sometimes they claim (as in the case in the Times story) that the property in question is their "ancestral estate," other times that it is due to them as reparations for slavery.

If there's one thing in the US that unites people of all races, it's cranky antigovernment conspiracy theories.

Sunday, September 26, 2021

Jane Smiley, "The Greenlanders"

Another entry from my old web site, a review of one of my favorite books:

I have long been fascinated by the Norse sagas. These great works of prose, written in Iceland in the 13th and 14th centuries, describe the deeds of the Vikings in their heroic age between 800 and 1050 AD. They are full of striking characters, human drama, and historical detail. I would say they are my favorite historical sources; I recommend Egil's Saga as the most accessible work of medieval literature for a student or a casual reader. And yet even I sometimes find the sagas hard to read. They were, after all, written 700 years ago, by people with very different ideas of what a story should be like, and they are strange to our ears. Their style is simple, almost spare, and events sometimes follow one after another without much reflection or explanation. The most famous sagas are those that concern the settlement of Iceland, and in these the authors flaunt their knowledge of genealogy in numbing parades of names and relationships. To read the sagas we must cross through an effort of will the barrier of time, and while that brings rewards of its own, it does not make for easy reading.

The gap between the sagas and the modern reader has now been bridged magnificently by Jane Smiley in The Greenlanders (1988). Smiley is best known as the author of books about contemporary Iowa, but though I enjoyed the first two books of hers I read that did not prepare me for the way I was swept away by this one. I have been completely absorbed in it for two weeks, and I felt great pangs of loss when I finally read to the end and had to close it and put it aside.

Smiley has adopted enough of the Sagas' rough, simple language to convey the feel of reading the originals, yet not so much as to erect any barriers between the modern reader and her story. She makes liberal use of some conventional saga phrasings, such as "People said..." and "It was the case that...." She uses some of the same scenes and literary devices as the saga writers, such as prophetic dreams, and descriptions of what characters see when they look over their own homes. Like the great sagas, her story is structured around a family and their disputes with their enemies. Yet The Greenlanders is a thoroughly modern novel. Smiley's characters have the psychological depth and the complexity of motivation that modern readers expect, and Smiley has a keen eye for the ironies of her story. With her guidance, it takes no effort at all to travel back across the long centuries.

The Greenlanders is the story of a family, the Gunnar's stead folk, and especially of a brother and sister, Gunnar Asgeirson and Margaret Asgeirsdottir. They live in Greenland near the end of the Norse settlement there; they are born in the 1350s, and the book ends not long after 1408, the date of the last written record of the Greenland settlement. Smiley weaves into the story the few events that are known to have taken place in Greenland in that time, and some of the characters have historical names. The lives of Gunnar and Margaret intersect with this historical narrative, but their story is composed mainly of family events: marriages, births, deaths, the loss of a farm field. The drama in the plot comes from a series of struggles over land and honor between neighboring families, and within the folk of Gunnar's Stead. These feuds, though, never really dominate the story, but blend in with the unending series of tragedies that define life in this harsh land: hard winters, epidemic disease, famine, isolation. In less skilled hands these hardships would be grim and depressing, but Smiley makes them seem like life as it must be, as a background against which every victory, even merely to live through the winter, stands out as a luminous wonder.

One thing Smiley adds to the standard saga narrative is the tale of two priests who come to Greenland with the last bishop, leaving behind the cathedrals and universities of Europe for a hard life ministering to the hard people of Greenland. While many of the people in the sagas are Christians, it cannot be said that the sagas' writers paid much attention to the spiritual side of life in their writing. Smiley does full justice to the role of Christianity in medieval life, and she portrays her priests and their struggles of faith with the cold eye of a great novelist. I enjoyed the doings of these priests nearly as much as the main narrative, and I think the add to the extraordinary historicity of The Greenlanders.

Surely of all humanity's experiments, the Norse settlement of Greenland is among the strangest. These Vikings lived as farmers in a land too cold to grow a single grain of barley or rye, or even a cabbage. They depended almost entirely on their cows, sheep, and goats, and on the seals and reindeer they hunted in season. In winter they walled their animals into their barns (a door would let out too much heat) and fed them such grass as they had managed to harvest from their meadows; often by the time the snow melted in the spring the animals were so weak that the men carried them out into the fields. The technology of medieval Europeans depended almost entirely on wood and iron, but Greenland offered none of either. Everything from the beams of their houses to their spoons had to be brought by ship. In return the Greenlanders offered walrus tusks, narwhal horns, white falcons, and woolen cloth, but they never had enough of these things to secure their comforts. All around them were Inuit who lived in a way well adapted to the rigors of the northlands, but the Norse had little interest in imitating their neighbors. They clung to their old ways, until, for reasons we still do not understand, they disappeared entirely from their land.

Smiley makes the harsh world of the Greenlanders entirely believable, and I found it thrilling to lose myself in that world with her. Gunnar Asgeirson and Margaret Asgeirsdottir will be among my friends now for as long as I live, and their marvelous story will be with me awalys. I am awed by this achievement, and I cannot recommend The Greenlanders highly enough.

March 23, 2001

Friday, September 24, 2021

The Footprints of White Sands

The footprints were first discovered in 2009 by David Bustos, the park’s resource program manager. Over the years, he has brought in an international team of scientists to help make sense of the finds.

Together, they have found thousands of human footprints across 80,000 acres of the park. One path was made by someone walking in a straight line for a mile and a half. Another shows a mother setting her baby down on the ground. Other tracks were made by children.

“The children tend to be more energetic,” said Sally Reynolds, a paleontologist at Bournemouth University in England and a co-author of the new study. “They’re a lot more playful, jumping up and down.”

Mathew Stewart, a zooarchaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, who was not involved in the study, said that the evidence that humans had left the footprints was “unequivocal.”

The footprints were formed when people strode over damp, sandy ground on the margin of a lake. Later, sediments gently filled in the prints, and the ground hardened. But subsequent erosion resurfaced the prints. In some cases, the impressions are only visible when the ground is unusually wet or dry — otherwise they are invisible to the naked eye. But ground-penetrating radar can reveal their three-dimensional structure, including the heels and toes.

Mammoths, dire wolves, camels and other animals left footprints as well. One set of prints showed a giant sloth avoiding a group of people, demonstrating that they were in close company.

The footprints were dated by deposits of ditch grass seeds interbedded with the sand layers. The dating seems pretty good, but this is a weird ecosystem and a weird soil configuration, so I think a lot more work will be thrown at figuring all this out.

There are two sides to the debate about when humans reached the Americas because there is strong evidence on both sides. On the one hand, the White Sands footprints are just the latest in a long line of archaeological sites dating to more than 14,000 years ago. On the other there is the undeniably evidence for the explosive spread of the Clovis people around 13,000 years ago, which is hard to explain unless the continent was empty of people. Modern genetic studies suggest that almost all Native Americans descend from a single founder population that lived on the order of 15,000 years ago. Other evidence, such as extinctions and fire frequency, also points to the Clovis period as the first when there were appreciable numbers of people around.

So the debate will go on. And meanwhile please ignore all the stories that say the 'Clovis first' theory is some kind of old-fashioned archaeological consensus that this new evidence overturns, because it has never been accepted by all American archaeologists and for the past 30 years it has been a minority view.

Links 24 September 2021

Scott Siskind reviews Martin Gurri's 2014 book The Revolt Of The Public, which explains the mostly leaderless, largely incoherent protests of the early 2010s (Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, the indignatos in Spain, etc.) as a petulant outburst of middle class rage against the governing elite, predestined to accomplish nothing. How does all of this look in the post-Trump era?

Mass grave of slaughtered Crusaders found in Lebanon.

Fighting about solar farms in Malta. First, the Environment Minister said no solar arrays can be placed on agricultural land, and now historic preservationists object to one being placed near one of the famous megalithic temples. Finding sites for solar and wind power is now the biggest obstacle to growth.

In the NY Times, a detailed account of how Israel used a remote-controlled, AI-assisted machine gun to assassinate Iran's top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakrizadeh, in November 2020.

The strange case of Frederic March, actor and civil rights activist whose name was stripped from university buildings in Wisconsin because he briefly belonged to a student organization called, apparently as a joke, the KKK. Local news story, article in Bright Lights, John McWhorter in the NY Times.

Ben Pentreath's summer, with photos of the Dorset garden and a trip to the Scottish islands.

Archaeology of private life: the eighteenth-century Canadian loyalist with eight mustard jars.

The anxieties stoked in upper-class Europeans by the practice of using wet nurses.

The collapse of Chinese property developer Evergrande threatens ruin for families and small construction firms across China, triggering protests outside company headquarters and then a government crackdown on the protesters.

The threat to water supplies from illegal marijuana farms in the US west.

Here is a historical achievement of sorts: the most miserable, uniformly pessimistic take on contemporary writing and the broader culture that I have ever read.

Kevin Drum has the data to show that Millennials are the highest paid generation in US history, despite all you have read to the contrary.

Two short Tyler Cowen posts on Ireland during World War II, drawn from two new works on Irish history. (First, Second)

To make an impact as an activist, take up a cause no one else is pursuing.

Interesting science fiction-themed graphite drawings by James Lipnickas.

The African Theater, North America's first black theater, opened in New York on September 17, 1821 and endured for about two years. (NY Times)

The street chairs of Cairo. Yes, people sit on these.

Google buys an office building in Manhattan for $2.1 billion and plans to add thousands of employees there, showing that 1) what our top companies care about is not low taxes but access to talent, and 2) that the housing crisis in our biggest cities is only going to get worse. (NY Times)

This week's music is Emylou Harris, who as a teenager performed on an outdoor stage a block from my office, an event two of my friends swear they witnessed: Goin' Back to Harlan, Wrecking Ball, Satan's Jewel Crown.

Thursday, September 23, 2021

Emancipation and Freedom Monument, Richmond, Virginia

Once upon a time the story of emancipation in Richmond would have been told with a statue of Abraham Lincoln entering the city, with a crowd of grateful black folks around him. I get why that wouldn't fly today but on the other hand it seems obtuse to me to ignore the part played by the Union Army and the Federal Government in the events of 1865.

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Higher Education and Political Morality

The other thing shown in the graph is moral progressivism (A), which the authors define as "a high level of concern for others and relatively low concern for traditional social order." That seems to me to be a tricky thing to measure, very sensitive to the particular issues you ask about. E.g., liberals might have a desire to defend traditional public schools, while conservatives might not be very interested in protecting that particular bit of the social order. (Unless they are high school football fans.) Business-allied conservatives support some parts of the social order but love "disruption" in the marketplace. And you can see from the graph that while moral progressivism correlates with more education, and with humanities and social science (HASS) rather than business or tech fields, the effect is weak and irregular.

To me the most interesting thing about the article was the authors' complaints about the difficulty of measuring these alleged effects. The one they found easiest to measure, relativism, turns out to have flipped ideologically since the 1960s, leaving them unsure how it relates to whether college makes students more liberal. They write about "victimhood culture," which is one of the most prominent culture war issues right now, but say nobody has been able to define it rigorously or figure out a way to measure it.

Which raises the question of to what extent these conflicts are as much about identity and personal style as they are about underlying ideology, and how deep their philosophical roots really run.

Bret Stephens touts Ritchie Torres for NY Governor

I read Bret Stephens' columns in the Times to get a sense of what the establishment, Wall Street-allied conservatives are thinking. So I was very interested in Stephens' piece praising Congressman Ritchie Torres, not AOC, as NYC's real progressive star:

The bigger mystery is why Torres hasn’t yet become a household name in the United States. On the identity-and-background scorecard, he checks every progressive box. Afro-Latino, the son of a single mom who raised three children working as a mechanic’s assistant on a minimum-wage salary of $4.25 an hour, a product of public housing and public schools, a half brother of two former prison inmates, an N.Y.U. dropout, the Bronx’s first openly gay elected official when he won a seat on the City Council in 2013 at the age of 25 and the victor over a gay-bashing Christian minister when he won his House seat last year.

He’s dazzlingly smart. He sees himself “on a mission to radically reduce racially concentrated poverty in the Bronx and elsewhere in America.”

In other words, Torres is everything a modern-day progressive is supposed to look and be like, except in one respect: Unlike so much of the modern left (including A.O.C., who grew up as an architect’s daughter in the middle-class Westchester town of Yorktown Heights), he really is a child of the working class. He understands what working-class people want, as opposed to what so many of its self-appointed champions claim they want.

“I don’t hire ideologues or zealots,” he tells me on a walk through his district. “Most of the people in the South Bronx are practical rather than ideological. Their concerns are bread and butter, health and housing, schools and jobs.”

What this translates to is a 21st-century civil rights agenda based on pressing working-class needs for affordable housing, better schools, safer streets, good health care. The goals are progressive, but the solutions, for Torres, have to be pragmatic.

That emphatically includes giving children the option to attend “carefully regulated, not-for-profit” charter schools, which his district has in abundance, over fierce opposition from teachers’ unions. “If there are parents in my district who have concluded that the best option for their children is a charter school, then who am I to tell them otherwise?” he asks.

Stephens even suggests that Torres should run for governor.

Which raises the question of why somebody like Stephens finds somebody like Torres appealing. I guess there is the conservative fondness for people who really raised themselves up out of poverty, rather than blaming others for their problems. Also the lack of interest in some of the issues that make white men uncomfortable, like Me Too and White Fragility. Torres has not been attacking capitalism and supports reducing the barriers to building more housing in cities. (Housing is his biggest issue.) He is skeptical of higher education as a solution for working-class woes and thinks we already send too many people to college. He doesn't hire zealots.

So here you have the sort of progressive that conservatives want to engage with: one not focused on culture war battles but on pragmatic solutions to real world problems. Some of Torres' solutions would be expensive, for example making Federal Section 8 housing vouchers an entitlement, but money can be negotiated.

Other progressives would say that this sort of focus on "bread and butter issues" means there will never be any real change, so of course Wall Streets supports it; somebody would probably say that this column is partly an attempt to redirect attention away from the sexual politics that recently dominated the state. (Forget Cuomo, forget sexual harassment, let's talk about this working class hero.) I'm not trying to make this a feel good story about bipartisanship; if Stephens lived in most other states he would not be touting any sort of progressive for governor. But I think this is an interesting insight into what Stephens, and I think many others, really fears, and what he might accept if it meant keeping the barbarians from the gate.

Monday, September 20, 2021

Merab Abramishvili

Prostitute, 1997

Terrorism and Freedom

Here's something interesting I found while going through the posts on my old web site: my response to the 9-11 attacks, written one month later. Some of it has aged well, some of it not so much. Since we just marked the 20th anniversary, that seems a good excuse to post this here.

Since the horrible morning of September 11 I have often felt shock and anguish, and I have sometimes been angry, but I have never for a moment felt afraid. When I said this to one of my friends she called me an "optimist" in a tone of voice that made optimists sound like a particularly stupid tribe of fools. I think, on the contrary, that it is foolish to be afraid of bin Laden and his crew. I believe that the chance that I or those I love will be hurt or killed by terrorists is small, so I see little reason to be personally afraid. A simple actuarial analysis shows that automobiles and high-fat foods remain much greater threats to most of us. More important, I think the fundamentalists' campaign to overturn western civilization has no chance whatever of succeeding, so that even if I die, the ideals I hold most dear will certainly survive.

I am not an optimist in any ordinary sense. I assume that we will never eradicate terrorism, let alone "rid the world of evil," as our President vowed. I am sure there will be more terrorist attacks over the next few years. I doubt, though, that there will be another terrorist attack as savagely successful as those of September 11. I think that while the US has experienced a great tragedy, it is bin Laden who has suffered a military defeat, because he has lost at least four of his best men while we have only been strengthened.

In the days just after the attack much was made of how different these terrorists were from the half-crazy 19-year-olds we are used to see carrying out suicide bombings: older, better educated, able to blend into western society and maintain their discipline during long stays in the US, far from their bases and support systems. Able, in particular, to fly planes. Now we know that only four of the terrorists, the pilots themselves, were of this new type, and the rest were angry young men who could have stepped off the terrorist profile sheet. I suspect that while al Qaeda can probably produce hundreds or even thousands of ordinary fighters, it has few men like the pilots of September 11 willing to kill themselves in its cause. Their loss has hurt bin Laden and lessened the chance of another catastrophic attack. Yet the attacks have not weakened the US. The shock of September 11 has only strengthened the hand of the US government.

The US will not be defeated by attacks like those of September 11, nor will such attacks ever challenge our civilization. Consider, by way of comparison, what Britain endured during the Nazi bombings of 1940: more than 35,000 civilians and hundreds of pilots killed in nightly raids that went on for months, thousands of buildings destroyed, whole districts leveled. By 1945, more than 60,000 British civilians had been killed. Yet neither the blitz nor the V weapons got Hitler not an inch closer to his goal of European domination. The spirit of the British public never wavered, and their military machine grew ever stronger despite the pounding of factories and bases. We are much stronger than the Britain of 1940, and we can better afford the loss of six buildings and six thousand citizens than al Qaeda can afford the loss of 19 soldiers.

Worried westerners have long feared that fanatics could defeat rational people and democratic governments through their greater commitment to their extreme beliefs. We see ourselves as the lukewarm proponents of ideals we are too comfortable to care very much about; our own happiness and satisfaction, we worry, may make us less fierce, less determined, less willing to sacrifice. We suspect, with Yeats, that "the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity," and we imagine moderation and reason overwhelmed by fundamentalism, extremism, and rage.

I think these fears are short-sighted and overblown. Our tradition of freedom and rational thought is now 2500 years old, and it has survived every assault thrown at it by fanatics and barbarians. The stream of free thought runs from Thucydides and Aristotle across the centuries to our own time, sometimes weaker and sometimes stronger, but never broken. The modern democratic state that institutionalizes these values is a much newer creation, but I believe it is a strong and great one. The British and American democracies are now more than 200 years old and despite strange detours and horrific conflicts the democratic spirit continues to spread across the world. The fear that we will be too weak and cowardly to defend ourselves should be assuaged by the simple fact that we have always been able to find the courage when we really needed it. The Japanese mistook American wealth and ease for cowardice, as did Sadam Hussein 50 years later. For anyone afraid that the world's rational people will lack the will to defend themselves, I recommend the memoirs of RAF pilot Richard Hillary (The Final Enemy), in which he explained that he was fighting as much as anything else to show that dissipated, irreligious, moderate men like himself could beat Nazi fanatics. He was right.

I do not feel defensive about the values of democracy: freedom remains a mighty ideal, as strong as faith, tradition, or utopian fantasy. Communism is retreating, the Soviet empire has collapsed, Slobodan Milosevic is awaiting trial in the Hague. Fundamentalism is indeed a powerful force all around the world, but I think most of its political appeal stems merely from the corruption and brutality of so many secular regimes. Consider what has happened in Iran since 1979. Khomeini's revolution succeeded spectacularly for a time, but within a decade ordinary Iranians came to realize that they did not much prefer religious tyranny to the Shah's secular savagery, and in the past few elections moderates have won the vast majority of votes. Where has a real, functioning democracy ever been overthrown by its citizens? Nowhere.

Freedom, tolerance, and self-expression are not merely the excuses of the rich or the justifications of the self-indulgent. Fundamentalists like to think that the secular majorities of democratic states believe in nothing, but they are wrong. We believe in the promise of humanity. We believe in exercising our own minds. We believe in the right to choose our own way, our own leaders, our own faith. These are ideals as powerful as any, and our belief in them is strong. The democratic system of government is not just a compromise among greedy factions, but one of humanity's greatest creations, the institutional embodiment of our noblest sentiments. The constitutions and declarations of democratic states are texts as rich in meaning as any scripture, as full of promise as any apocalypse. As the leaders of democratic revolutions have always asserted, we were born to be free, not to be the slaves of tyrants or the pupils of priests. We must not be afraid of terrorists, or of the dark attractions of fanaticism and rage. We should take our stand on the ground of free thought, free speech, and freedom to pursue our own good in our own way. Here we will never be defeated.

October 14, 2001