Storks return to a Ukrainian farm destroyed in the war

India's total fertility has fallen below replacement.

The Como Treasure, a hoard of gold coins from the 5th century.

And the Rogozen Treasure, marvelous Thracian gold.

Outside report on the handling of sex abuse allegations within the Southern Baptist Convention finally lands, raising once again the question: can the reputation of any institution survive an honest accounting of what its leaders are and do? (NY Times, CNN, Christianity Today)

Using the tiny fossils known as coccolithophores to understand past climate catastrophes.

This is America: "A motel room that Alabama corrections officer Vicky White and escaped fugitive Casey White turned into their hideout now has a waiting list."

Commission ordered by Congress recommends new names for US military bases now named after Confederate heroes.

Margaret Atwood with a flamethrower.

Three mainstream state legislators in Kentucky, committee-chair type guys, ousted in the primaries by Tea Party-aligned populists.

On the other hand, established Georgia Republicans sweep away a challenge from Trump-backed election deniers in races for governor and secretary of state. (NPR)

Thomas Edsall talks to political scientists about polarization, finds that they do not agree at all about how polarized Americans are and whether polarization is wrecking our politics. (NY Times)

If you ask Americans how they feel about "income redistribution," you get a big partisan difference, but if you ask about the various taxation and spending programs that make up government redistribution efforts you get much smaller differences.

An economic historian bashes the New York Times' recent series on Haiti. And more here. Seems to me it has the same basic problem as the 1619 Project: it poses as scholarship but is produced by journalists with a lot of political axes to grind. Yes, academics who attack these series resent the intrusion of a newspaper onto their turf, but they have a point, because newspapers are not set up to produce scholarship.

Interesting that people in both New Guinea (and here) and Canada's northwest coast made sculptures called "spirit canoes" that had important ritual uses.

Ben Pentreath photographs spring in Scotland and Dorset.

Tyler Cowen remains a little obsessed with UFOs. My response is "call me when you have real data." Seriously, there are millions of things in the universe we cannot explain, starting at the very base with our inability to reconcile relativity and quantum mechanics, so a few dozen unexplained radar blips do not impress me.

L. Frank Baum as a creator of fantastic window displays for department stores.

Scott Siskind on the Hearing Voices movement, peer psychiatric counseling, and more. Bonus: Siskind's Cheat Sheet for Reading Popular Articles about Psychiatry.

Heavy drinking, hiding wine bottles from reporters, fights among the drunken staff, and flouting of Covid rules at No. 10 Downing Street under Boris Johnson. With karaoke machines. Fascinating, the sort of people who end up running the world.

Thinking over the Boris Johnson "partygate" story, I am struck that for some people "partying" – drinking, music, an atmosphere of abandon – is an activity as vital to life as reading and walking are to me.

Ukraine Links

Timothy Snyder: Russia is a Fascist state.

Ukraine's former defense minister explains why Ukraine can win the war.

Zelensky's spokesman Arestovych worries that European nations are buying into Russian propaganda that once they finish their offensive, that is the natural place to make peace, and any Ukrainian efforts to reconquer territory will be warmongering.

Video is circulating showing a trainload of Russian T-62 tanks brought out of storage and sent toward the front. Not only are they 50 years old, they use a size of shell not used by any modern gun, so they would need their own separate supply train. And they have a manual loader that no Russian troops have been trained to operate for years, which has led to speculation that they are intended for the older reservists who may be called up under a new law. But pulling tanks out of deep storage is what you have to do when your army has lost at least 700 tanks during the war.

CNN piece based on an interview with an American volunteer who fought at Irpin in the early stages of the war, interesting.

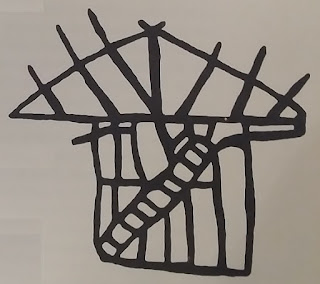

Below, a series of links on Russia's recent, significant advances in the far east. You can see this as a shrunken remnant of Russia's once grandiose invasion plans (see image above), but on the other hand by concentrating all their artillery and air attacks in a small area the Russians are mauling Ukrainian forces and making real progress. Opinions differ as to whether this is Russia's last gasp, and too small to matter much anyway, or a sign that Russian firepower is finally starting to break Ukrainian resistance. Ukraine's own offensives, around Kharkiv and toward Kherson, seem to have petered out.

Igor Girkin summarizes recent Russian advances and Ukrainian withdrawals in Donbas.

Thread and map from Jomini covering recent Russian advances.

Interesting NY Times feature on the shrinking area of heavy fighting, with good maps.

Institute for the Study of War summary for May 24, with an assessment of new Russian plans.

Thread by Michael Kofman, who is more impressed by Russian gains and not sure the offensive will run out of steam soon. I agree with him that recent Russian advances are a sign that Ukraine's forces in the east have been significantly degraded.

And another analysis, this one focusing on topography.

.jpg)