The grid is striking, and it is also interesting that later Maya cities did not follow this plan. The rectangular grid was tried once and, so far as we know, not used again for centuries.

Interestingly, most of the archaeology done at Nixtun-Ch’ich’ has focused on a later period, because this is one of the Maya towns that was occupied through the collapse of classical Maya civilization and into the colonial era. Alas, less has been learned about that period than you might hope, because everywhere they dig archaeologists find mainly artifacts and buildings from the city's glory days. But that it itself tells you something about Maya urban life after the classical collapse in the 10th century.

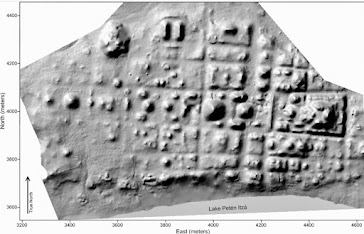

Enter a certain Timothy Pugh, a professor at Queens College in New York, who made the archaeological news this week by re-publishing the Lidar map and making a bunch of comments about it.

Pugh notes, with some justification, that this plan represents a powerful central authority, able to exert its will on the plan at a time when other cities seem to have grown more organically:

“It’s a top-down organization,” Pugh said. “Some sort of really, really powerful ruler had put this together.”

And woe betide the people who had to live there:

While the city was a sight to behold, its people might not have been happy with it, Pugh said. “Most Mayan cities are nicely spread out. They have roads just like this, but they’re not gridded,” said Pugh, nothing that in other Mayan cities, “the space is more open and less controlled.”

Cities in Renaissance Europe that adopted rigid designs were often unpleasant places for their residents llive, Pugh said. It’s “very possible” that the residents of this early Mayan city “didn’t really enjoy living in such a controlled environment,” Pugh said.

I notice that even the scribes at the Archaeology News Network, who usually just parrot whatever excavators tell them, put quotation marks around Pugh's comments. Because so far as I am aware there is exactly zero evidence that people living on rectangular grids are less happy than those living on curving roads or crazy-quit urban places like old London. If you're vaguely remembering urban studies that extolled organic urban neighborhoods against centrally planned areas, that has more to do with rigid zoning that separates business and residences than the plan of the streets. There are plenty of funky urban neighborhoods with rectalinear street plans.

This is Copenhagen, which often shows up in studies as the best place to live in the world. Old Amsterdam, another contender, follows a bunch of perfectly straight canals and is also pretty thoroughly gridded, certainly more so than Nixtun-Ch’ich’. I doubt Professor Pugh would have much good to say about the curving streets of my suburban bastion.The city was divided into four zones, or camps; each camp was divided into 20 districts (calpullis); and each calpulli, or 'big house', was crossed by streets or tlaxilcalli.

I ought to be used to archaeology professors saying nonsensical things by now, but somehow their foolishness still lands in my head with a loud thud.

No comments:

Post a Comment