Slavic folk tradition exhibits notions about the dead person having to travel long distances here on earth in order to reach the land of the dead; or over a rainbow or across the Milky Way; or up a steep mountain of iron or glass; or sailing after death to a land beyond the ocean, sometimes imagined to be situated at the place where the sun sets, sometimes being simply an island; the land of the dead may also be situated beneath a certain lake, or the dead person may be thought to inhabit his grave. Siuts has demonstrated this kind of variation in German folktales: in order to get to das Jenseits [the beyond] – the troll or the land of the dead, in many cases – one has to travel far, and farther than far, maybe through several kingdoms and over the sea or a big river, or a bridge; or one has to get across a silver mountain or a golden mountain on the way, or across an endless plain, or through a large, thick, dark forest; in some cases one has to go to the sun or the moon; or into a hole or shaft in the earth, or a well; far, far down; or into a hole or through a passageway leaning in a vertical direction or leading up into the daylight in the otherworld; or up onto a mountain, preferably one that reaches into the sky and is steep and smooth as glass; or a mountain may open, so that one may enter it. This kind of variation is found also in Norwegian folktales, and in other ethnic religions, and partly also in the large book religions. In ancient Greek religion one imagined lands of the dead situated both in the underworld (Hades) and on a western island or islands of happiness (for the chosen), not unlike that imagined by the insular Celts, or in or at the grave. In Jewish tradition, the mythological purgatory Gehenna seems to be located both under the sea and/or under the ground; or at the foot of a mountain range.These contradictions have been driving the literal-minded crazy since they were debated in the agoras of classical Greece. The passage above comes from an article by Eldar Heide (has any folklorist ever had a better name?) that I downloaded from Academia. Heide can cite dozens of scholars from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries expressing frustration over the inconsistency of myth and proclaiming that the ancient Norse cannot be said to have even had a cosmology, since they couldn't decide if heaven was in the sky, in the east, or around the corner.

Beowulf, you may recall, swims down through the water to reach the cave where he battles Grendel's Mother. As a foolish young undergraduate I was taken by an eminent professor who said this must mean that the hero had swum under a waterfall and then up into a dry cave. I deeply regret that even at 20 I did not see through this pseudo-rational claptrap. Because, I mean, an author who fills his tales with monsters and a dragon couldn't possibly be so foolish as to think you could swim down through the water to a dry place.

This scholarly stubbornness is genuinely baffling to me. The answer has never really been forgotten, as hard as various scholars tried to ignore it. The Beyond, in whatever form – the abode of the gods, the land of the dead, the kingdom of the elves – is the place we visit in dreams and visions. Asking where it lies is the same as asking where we go when we dream. Now to you that may seem like an absurd question, but across most of human history it was not, and many different traditions have insisted that the place of dreams is at least as real and fundamental as this one. But as anyone who has ever dreamed knows, dreamland is not like this world, and it is not bound by the same rules. Including rules about time and space.The model for all heroic journeys, for all travels to the realms of the dead or of the gods, is the shaman's trance, and beyond that the dream. To ask whether shamans go east or west, up or down, is absurd. When asked – and anthropologists have been asking them since the 17th century – they do not speak in such terms. They go to, and past, and through; they may follow a chain of landmarks, or pass a series of tests. But mainly, they go away; away from this world and its rules and limits. Any direction will do, so long as it is away and not back.

I am tempted to call all the endlessly varying stories about these journeys metaphors, but I am not sure that is right. They convey many meanings. They tell us that the Beyond is difficult to reach, and that once we get there our story will not be bound by earthly rules. They convey the special prowess of the tale's hero or heroine, who can go where others cannot. But they do not describe places or routes one can put on map, because at the most fundamental level they take place within us, where such diagrams have no meaning.These stories convey that the universe is more than the earth where we live our waking days, and whose rules we understand. There are places we cannot usually see or reach, places populated by different beings, some with awesome powers. They also tell us that we can sometimes cross to those worlds, and that sometimes our world intersects with some other in a way that may be wonderful or terrible. They tell us to be alert for wonders.

The tales tell us that not all knowledge can be expressed in straightforward sentences spoken by daylight. Some truths are secrets, hardly ever revealed, or mysteries, easy to speak of but very hard to understand. They tell us that the universe is awesome; that it is beyond us and above us and in us all at once; but that with the power of our minds, with our intelligence and our courage, we can journey through it, and expand our lives far beyond the huts and houses where we sleep and eat. We may be born in this world, but we are not confined to it, any more than the wind, any more than the gods.

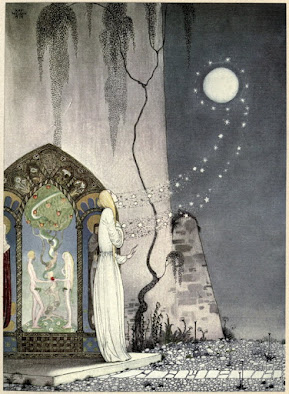

(All of the pictures here are illustrations to the same folk tale, East of the Sun and West of the Moon; one of the things that varies from version to version is the magical means by which the heroine travels to that impossible place.)

No comments:

Post a Comment