More than a few people in New Jersey tried to cultivate good relations and strong alliances with both sides. Among them was the Van Horne family, who became highly skilled at this dangerous game. Philip Van Horne was a New York merchant who left the city at the start of the Revolution and moved to a country estate called Convivial Hill or Phill's Hill near Bound Brook in Somerset County, New Jersey, between the armies. He had a large fortune, a habit of hospitality, and five very attractive daughters. Philip's brother, John Van Horne, died at the beginning of the Revolution leaving a widow and three daughters more. The two households visited back and forth and were often confused. Altogether there were eight young "Misses Van Horne," as they were collectively called, "all handsome and well bred." They attracted swarms of officers from every army.David Hackett Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2004)

Philip Van Horne was a good friend of New Jersey's Whig governor William Livingston. He also maintained good relations with British and Loyalist officers and received them in his home when they were in the neighborhood. When the American army arrived, they were welcome too, and many American officers stayed in his house. Captain Alexander Graydon found that Mr. Van Horne "alternately entertained the officers of both armies, being visited by one and sometimes by the other. . . . His house, used as a hotel, seemed constantly full."

It was, if nothing else, a considerable feat of scheduling. In the worlds of Leonard Lundin, the Van Horne's "performed prodigies in the difficult art of being all things to all people." Philip Van Horne carefully cultivated friendships with high officers in every camp. He kept up his friendships with leading New Jersey Whigs and cultivated connections with Loyalists and British leaders. He also made a point of doing favors for both sides. When Graydon was captured at Fort Washington, Philip Van Horne helped the soldier's mother to win his release.

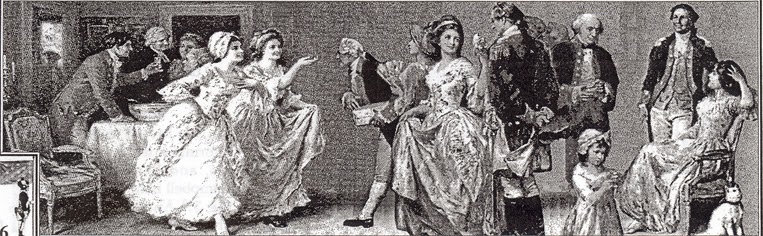

His beautiful daughters cultivated connections with younger officers on both sides. As the war went on around them, they danced and flirted happily with men in many uniforms. They encouraged visiting Americans to believe that they were "avowed whigs." British and Hessians took them to be secret Loyalists. Many knew what they were doing, but their combination of genteel Whiggery and sociable Toryism added to their attraction. They were known for "civility to the British officers, hospitality to the Hessians, and sympathy for Americans."

When the Misses Van Horne were in the country, they were courted by Continental officers. When they went to Flat Bush in New York, they were entertained by the British garrison and invited to balls for royal anniversaries. Sometimes the Van Horne sisters were with their uncle in New Brunswick, where Hessian gentlemen came to call. Jaeger Captain Johann Ewald fell madly in love with Jeanette Van Horne. He sent her gifts of "sausages made in the German manner," game birds that his men had shot, and passionate love letters in fractured French. . . .

General Washington did not approve of the ambidextrous Van Hornes, and Philip Van Horne in particular. On January 12, 1777, he wrote sternly to Colonel Reed, "I wish you had brought Vanhorne off with you, for from his noted character there is no dependence to be placed upon his Parole." A few weeks later Washington thought that Van Horne should be ordered into British lines: "Would it not be best to order P. Vanhorne to Brunswick -- these people in my opinion can do us less injury there than anywhere else." But not even George Washington could restrain the Van Hornes. They remained at liberty and flourished happily in an eighteenth-century world where distinctions of rank and wealth sometimes proved more powerful than politics or war.

Saturday, April 25, 2015

Entertaining Both Sides

New Jersey, 1776;

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment