And that, right there, exhausts all certain knowledge about them.

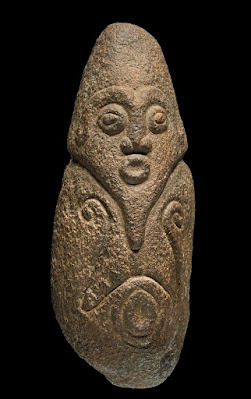

These are not obscure; there are thousands of photographs online, and outsiders have been asking local people about them and writing down what they said for more than a century. That just hasn't led to much certain information, or even agreement about probabilities.While the stones are quite important to the people in these villages, the locals do not agree on what they represent. "Oral traditions," the British Museum tells us,associate numerous meanings with the stones. For example, stone circles are used as places of sacrifice and community meeting places. They were created as memorials of departed heroes or beloved family members and represent powerful ancestral spirits to whom offerings are still made. In addition local community leaders also ascribed religious significance of the stones whereby particular stone are dedicated to the god of harvest, the god of fertility and the god of war.Via the magic of JSTOR – don't we live in an age of wonders? –I found an interesting 2015 paper by Sandy Onor, a Nigerian historian, published in the Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, which notes that in one village the people say the monoliths represent past chiefs and can tell you the name of each chief.Incidentally the most common word for these in Ejagham is Akwasnshi, which means "dead people in the ground." But there is no evidence that they are grave markers.Just as with the Pictish symbol stones in Scotland, there is a strong suspicion that the various shapes carved on the stones are symbols, possibly a form of "symbolic communiciation," i.e., writing. But, if so, nobody has any idea what they mean.How old are they? Nobody knows. The main point of the Nigerian paper I just mentioned was to try to date them by comparing the various possible methods and seeing if they could be lined up. The only archaeology the author could find was a single study that involved digging one trench, finding one hearth, and getting one radiocarbon date, which came out around 200 AD. Which is fine, so far as it goes, but there isn't any particular reason to think that hearth was associated with these stones, I mean, people often set up their stones in places that have long been considered spiritually potent. (e.g., Stonehenge)Since people in one of the villages insist that their stones represent chiefs, he tried using lists of rulers as a chronology, using a figure of 13 +/- 5 years for the average reign that he says is widely used in west Africa. That got him to around 1500 to 1600 AD.Then he tried using genealogies, which are particularly good for the Ejagham since they count by both mothers and fathers, giving two generation counts for each person. Those get you back to around 1800, and, he says, there is other evidence that the Ejagham people migrated to the Cross River region between 1740 and 1820. (The intense period of the Atlantic slave trade in the 1700s badly shook up west Africa, leading to many migrations.)

So, you know, good luck sorting that out. One possibility, which nobody I have found seems to have considered, would be that the Ejagham didn't make these at all, but found them in place when they came to this region. Certainly nobody ever observed an Ejagham man making one of these, so their manufacture had ceased by 1900.

In many of the online photographs, the stones are painted; it took me hours to find a reference explaining that this is done for the annual yam festival.Like this.Anyway, what a fascinating thing, a collection of marvelous stone statues still venerated, but by people who may not have made them and do not agree with each other about how old they are, what they represent, or what the symbols on them mean.

No comments:

Post a Comment