The main theme of this memoir is how great it was to be a rich Jewish aesthete in Europe before 1914, and how badly everything went wrong thereafter. The tone at the beginning is warm and nostalgic, turning increasingly to bewilderment and bitterness as things in Europe get ever worse. The book is famous among conservatives of a certain sort, the ones who like stability, order, and doing things just because they have always been done that way. Yet Zweig was also critical of the old order, in ways that I think point toward why its collapse was inevitable. I found it most interesting as a document of a certain kind of person, the artist and art lover who mainly wants to be left alone to create and enjoy creation.

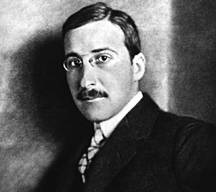

Stefan Zweig was born in 1881 into a family of Jewish industrialists. Since his older brother was genuinely interested in taking over the family business, he was free to ornament the family by pursuing an intellectual life. Early on Zweig makes an interesting observation about art in the later nineteenth century. Vienna had been a great city of music since the 1750s, but by Zweig's time the financial underpinnings of Viennese music had completely changed. In the eighteenth century music had been supported by the imperial family and other great aristocrats. But by 1860 the aristocracy had pretty much given up artistic patronage, and instead artists were supported by the bourgeoisie through subscriptions to the Philharmonic and the Opera. Among these bourgeois art supporters, Jews were especially prominent. The same was true of theater and painting. Families like Zweig's not only held subscrptions and memberships to all of the city's major artistic venues, they happily supported him for years as he he studied and wandered Europe and imagined himself as an artist. Wealthy Jews threw themselves into European culture, Zweig among them.

The Austrian school Zweig attended sounds much like the British one that George Orwell wrote about. The students learned a great deal, because if they did not they were punished and humiliated. Zweig's account is dark and bitter in tone, focusing on the emotional deadness of the place and the alienation of the students. And yet his future life was made possible by the languages he learned: French, Italian, English, Latin and Greek. He emerged marvelously educated. Orwell at least thought the two were connected, and that there is no way to get boys to learn Greek without beating them. It is the first glimpse of many in the book that the good things about 19th-century Euope were inextricably bound up with the bad ones.

The other thing about 19th-century life that most bothers Zweig in this book is the sexual hypocrisy, and in particular the way upper class girls were kept completely ignorant of sex. In his family there was an oft-told story of an aunt who fled on her marriage night to her sister's house in terror of the horrible things her husband had tried to do to her, "which she had only just escaped." Zweig, who was later a good friend of Sigmund Freud, finds all of this ridiculous, and praises the new sexual mores of the 1920s. In that time young people could interact "naturally," he says, without the bizarre rules and restrictions of the earlier era. But was maybe the intense artificiality of so much about 19th-century Europe part of the secret to its stability?

At 15, Zweig decided to become a poet, and from then on his life was mostly about art. When he was still in the university he published a book of poems (which later embarassed him) and soon after graduation landed an essay in the Arts section of Vienna's top newspaper. (That was what really impressed his family, who took their ideas about culture from its pages). But it was a long, winding road from those early successes to a mature literary career. Zweig spent much of the intervening time abroad, living for extended periods in Berlin and Paris and a shorter time in London, traveling to Italy, India, and the United States. He must have been a charming man because he made friends with artists wherever he went. The best writing in this book is Zweig's accounts of the world his artistic friends inhabited. I already posted his description of a visit to Rodin's studio, and there is an even better portrait of the poet Rilke, too long to post here, a shy man of such extraordinary sensitivity that he could not tolerate loud noises or work in an over-decorated room. Rilke could speak wonderfully to one or two others, but if he found himself at the center of a larger group he would stop talking and slink away. What most impressed Zweig in those years was the extraordinary devotion of artists to their work, the way many of them lived modest lives in cramped apartments or in self-imposed exile, nothing mattering but creation and the cultivation of creative friends.

Until World War I, by his account, Zweig paid no attention to politics. He considered himself a European, equally at home in Austria, Germany, or France, with friends in every nation on the continent. All he asked from his government was to be left alone. What he praises about the politics of that era was the freedom, the fact that he could travel anywhere in the world without a passport or a visa, that his bags were never searched, his papers never checked by the police, his income never audited or even declared. He admits that Austrian workers had no real political power, but he seems to wonder why they even wanted such a thing, since the old Imperial government was doing just fine as far as he was concerned. The appearance around 1900 of populist parties, some of them anti-semitic, struck him as an irrelevent absurdity, not worth his attention. Nor did he pay any attention to colonial events. This, it struck me, was a mistake, since when the Great War came Zweig was flabbergasted by the violence of his contemporaries, whom he took for peaceful and peace-loving. A glance at the brutal wars in Africa might have shown him the truth on that point.

But the biggest weakness of the first half of the book is that at no point in it does Zweig even acknowledge that his life was great because he was rich, and that much of the freedom he enjoyed was purchased with his money and class. He neither knows nor cares what workers and peasants were up to, so long as they left him alone. It was only when they began voting for radical parties with angry leaders that he even mentions their existence.

The chapter on 1914 is excellent and moving. Zweig was bewildered by the extraordinary displays of nationalist emotion that broke out in every direction. The first emotion was joy:

Next morning in Austria, there were notices up in every station announcing general mobilization. The trains were full of recruits who had just joined up, flags waved, music boomed out, and in Vienna I found the whole city in a fever. The first shock of the war that no one wanted, not the people or the government, had now turned to sudden enthusiasm. Parades formed in the streets, suddenly there were banners, streamers, music everywhere. The young recruits marched along in triumph, their faces bright because they, ordinary people who passed entirely unnoticed in everyday life, were being cheered and applauded. To be perfectly honest, I must confess that there was something fine, inspiring, even seductive in that first mass outburst of feeling. In spite of my hatred and abhorrence of war, I would not like to be without the memory of those first days. Thousands and hundreds of thousands of people felt, as never before, what they would have been advised to feel in peace—that they belonged together. . . . Differences in social station, language, class and religion were sumberged at this one mement in a torrent of fraternal feeling. Strangers spoke to one another in the street; people who had avoided each other for years shook hands.

But as the war dragged on, joy turned to hate. Zweig, judged unfit for service and working as a clerk in an obscure corner of the war department, was dismayed that most of his intellectual friends joined in drumming up hatred of the enemy. He knew the man who wrote a briefly famous poem, The Hymn of Hate for England, and others wrote every day about British and Russian perfidy. This was Zweig's first experience of mass propaganda, and he was dismayed at how effective it was:

Modest tradesmen stuck or stamped the slogan Gott Strafe England —God punish England—on their envelopes, society ladies swore never to speak a word of French again, and wrote to the newspapers saying so. Shakespeare was exiled from German theatres, Mozart and Wagner from French and British concert halls. German professors explained that Dante had really been of Germanic birth, while the French claimed Beethoven as Belgian. . . . Mental confusion grew worse. The cook at the stove, who had never left her town and hadn't opened an atlas since she was at school, was sure that Austria could not survive without the acquisition of Sandshak (a small border village somwhere in Bosnia). In the street, cabbies disputed the amount of war reparations to be demanded of France, fifty billion or a hundred billion, without knowing how much a billion was. There was no town, no social group that did not fall victim to the terrible hysteria of hatred.

Zweig, determined to take some sort of stand against the war, hit on the idea of writing a play about the prophet Jeremiah. Jeremiah's warnings about a terrible coming storm were ignored by his contemporaries, which Zweig thought was close enough to events to be meaningful while being distant enough to perhaps slip by the censors. He wrote this in verse – it always struck me as strange that in the early 20th century, amidst radical artistic experiments of every kind, there was a vogue for plays in verse, but such it was – and by the time he finished it was too long to even perform on a single night. He did not really think it could be published, since the war was still raging, but this was in 1917, and beneath their patriotic exteriors many Europeans were sick of war. It was published as a book and the initial press run of 20,000 copies sold out in a day. It was performed in Switzerland, and the Austrian foreign ministry made no trouble about giving Zweig a visa to spend six months in Zurich to assist with the production. Zweig had the seductive experience of taking a lonely stand and then eventually seeing the rest of the world come to agree with him. Yet he did not dwell on this in 1942, because by then he had been proved dismally wrong many times over.

The chapters on the 1920s are also good. I especially liked the portrayal of life amidst the extraordinary inflation that struck first Austria and then Germany. People generally felt that if you had any money, you should just spend it, because it would be worth less tomorrow. Bars, theaters and nightclubs therefore thrived. Things eventually settled down, and life went on. In some ways, as I mentioned, Zweig liked this time better, with its sexual openness and crazy artistic explorations. Zweig also finally achieved major success as a writer. He wrote poems, plays, essays, novels, librettos for operas, but above all best-selling biographies of historical figures. He made the rundown house he had purchased just before the war into a showplace where he entertained artists and writers from all over Europe. Life was good.

And then came Hitler. The final section of the book is short, really only a sketch. Zweig tells only one memorable story, about his work with Richard Strauss on the opera Die Schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman). Strauss was one of many Germans who tried to have it both ways under Hitler, collaborating enough to retain his important posts, and even to become a major figure in the culture ministry, while maintaining some autonomy and keeping his Jewish friends. One of his gestures of opposition was hiring Zweig to write the libretto for his new opera. He announced this quite publicly, almost daring the Nazis to stop him. Such was the admiration of leading Nazis for Strauss that it went ahead, and the opera received its first two performances. But then the Gestapo intercepted a letter in which Strauss was contemptuous of Nazism, which enabled Strauss's opponents to outmaneuver his defenders, strip him of his government posts, and shut down the opera.

Seeing that Austria would soon fall to Hitler, and that there was no place for him in Hitler's Europe, Zweig fled to England. At first his life there was pleasant enough, but then war broke out and as an Austrian citizen he became an enemy alien, under severe restrictions. So he moved to Brazil, where he seemed for a time to be relatively happy. He wrote this book, but even before the end he found that he had no more to say. In the face of Nazism, he could only fall silent, even into the silence of death.

For me, The World of Yesterday raises anew the question of what happened to Europe, and it points toward at least three answers. The first would be that the peace of the nineteenth century was only maintained by a fierce sort of oppression, mainly exercised not by the police but by society at large, and that when this oppression cracked bad things were bound to happen. Writing about his schooldays, Zweig asks himself why the authorities were so harsh on any kind of boyish exuberance:

All that now appears enviable – the freshness of youth, its self-confidence, daring, curiosity and lust for life – was suspect at that time, which set store solely on all that was well established. Only that attitude can explain the way the state exploited its schools as an instrument for maintaining its authority. Above all, we were to be brought up to respect the status quo as perfect, our teachers' opinions as infallible, a father's word as final, brooking no contradiction, and state institutions as absolute and valid for all eternity.

This was indeed the world imagined by 19th-century conservatives, in which order in society rested on children obeying their parents, wives obeying their husbands, students obeying their teachers, and everyone obeying the Kaiser and the state. Did the stability of the society ultimately rest on absurdities like teachers whipping boys who didn't do their Latin homework? Is youthful "lust for life" an expression of a dark anarchy at the heart of all humans, that has to be controlled for civilized life to emerge and endure? Did destructive impulses, caged for so long, eventually break their bounds and explode across the world?

You could also see Zweig's memoir as reinforcing the point made by Thomas Mann in The Magic Mountain, that things fell apart because the good people stopped paying attention. Much of Europe's liberal elite was like Zweig and Mann, happy to just get on with their lives on the theory that their world was stable and strong. If Mann's book does indeed use people marooned in a Swiss sanatorium as a metaphor for an upper class entirely detached from events in the political and economic world, Zweig would be the Mountain's perfect inhabitant. Hanging out it cafes with other aesthetes, talking only about art, they failed to even notice that their world was dissolving beneath them.

I am most attracted to a third view that I associate with Roberto Calasso. For all that the nineteenth century was in some ways intensely rigid and conservative, it was also an era of constant, profound change. I tend to see the sexual and social conservatism of the era as a reaction to all of that change, an attempt to maintain psychological steadiness amidst the unprecedented transformation of the world. In politics, stability was maintained in Britain, France and Germany by a steady expansion of rights for peasants and workers. It turned out, though, that just getting the vote did not satisfy people, and that once they had political rights they used them to fight for change that would benefit them. As Lenin and many others pointed out, there was an absurdity to bourgeois democracy in this period, which somehow assumed that workers and peasants could be kept from demanding real equality with talk of order and civilization. In this view Europe rode with relative peace on a tide of change for a century, but the contradictions that built up were bound eventually to lead to some kind of crisis.

Zweig's memoir offers no conclusions, only observations. I found them fascinating, but the book did not do for me what it seems to do for many others, because I did not finish it wishing we could bring back the world before 1914. I like my own time better.

10 comments:

The main theme of this memoir is how great it was to be a rich Jewish aesthete in Europe before 1914, and how badly everything went wrong thereafter.

In that time young people could interact "naturally," he says, without the bizarre rules and restrictions of the earlier era. But was maybe the intense artificiality of so much about 19th-century Europe part of the secret to its stability?

Uh, if it was so stable, why did it change? This is like asking, he seemed so healthy and stable, why did he drop dead? Is John suggesting that keeping people so ignorant of sex that a married woman would flee from her honeymoon night in terror is what kept things stable??

In a word, yes. My idea is that societies are whole, organic entities, and that you can rarely change one thing about them (e.g., their sexual morality) without changing a lot of other things. I think that to imagine we could have the good things about life in Europe between 1875 and 1914 without all the bad things is a mistake.

"But was maybe the intense artificiality of so much about 19th-century Europe part of the secret to its stability?"

Pardon? Did you say stability?

We're talking about the century that started off with Napoleon trying to conquer the world, yeah? The century where society all across Europe was being transformed in never-before-conceived ways via rapid industrialization? The century where rampant Nationalism was resulting in the maps being radically redrawn every decade or so as some old state splintered, or where some new one arose, often by consolidating many smaller one a la Germany and Italy? The century where Europe decided to abandon slavery, an institution that had existed since the dawn of civilization? The century in which massive waves of migration occurred, upending the demographic makeup of the continent? That century? The famously un-stable one?

Now, I'll give you this much - the intense artificiality of the era was almost certainly an effort to impose stability. Many people weren't exactly thrilled by all the change and instability of the era, and they tried a great many ways to impose order on things artificially.

But that said, I almost stopped reading entirely based on that "stability" comment, as it stuck out like a sore thumb and made it hard to take you seriously. (Particularly so close on the heels of seeming to advocate teaching language through beatings.)

Hanging out it cafes with other aesthetes, talking only about art, they failed to even notice that their world was dissolving beneath them.

Sounds like several period in Japanese history, where the wealthy elites were detached from the world, obsessed with art and culture, while the brutal realities of shogunate-daimyo politics ground on bloodily all around them.

Fascinating review. Funny, I just last week saw Tom Stoppard's "Leopoldstadt," which covers much of the same ground, starting in pre-WWI Vienna. One of the characters remarks jeeringly about the naivete of 19th-century liberals who gave the vote to the masses, only to have the masses vote for Karl Lueger and his ilk.

My impression is anti-Zionism is one of Zweig's themes, explicit or not--as it is, in a very understated way, one of Stoppard's. "Talk all you want about how great it would be to till fields alongside members of your own ethnos; I got to spend a day with Rodin!"

I imagine one could make a case that much of what critics often think of as bad in our own culture and that is very much the opposite of stereotypical pre-1914 culture--eg, liberated sexuality-as-entertainment, or an undemanding, arguably almost empty educational system--helps promote whatever stability we have here. Not that I want to make a case for corsets and beating children so they will learn Greek--I'm simply struck that both extremes on sexuality and education (just to take two fields) can serve the same function.

@David- Zweig does mention meeting Herzl and being impressed but ultimately not being able to agree with him. Zweig shows zero interest in poor Jews, or indeed in any kind of Jews except his family and Jewish artists. He portrays himself as living as fully as possible in the world of European art and letters. Which was, he makes clear, full of Jews, but that was not really the point.

>I think that to imagine we could have the good things about life in Europe between 1875 and 1914 without all the bad things is a mistake.

I think that to imagine we could have the good things about life today without all the bad things is a mistake. There's always good and bad things. If you think not telling women about sex up to and beyond their weeding night kept society 'stable', I think you should be wearing a tinfoil hat. And as G. said, the 19th century being 'stable' is a truly odd idea. Who thought we would ever agree? And again, if it was so 'stable', why did it not last?

"He was so stable right up until he went nuts and shot himself"

@John--Yes, it's ticklish having as one's anti-nationalist spokesperson such an obviously out-of-touch elitist snot. Especially when one really just want to protect one's own middlebrow, deracinated, but still *very* pleasant and cushy American consumerist fandom.

Reading about Zweig as you, I expect, quite faithfully present him, one can almost (I stress *almost*) sympathize with the Viennese masses for wanting to say, "Oh yeah, take THAT!" (Yeah, I know I'm verging on the unthinkable there.) On the other hand, Zweig's joy in his afternoon with Rodin seems so genuine and complete and unaffected, so "simple" in the best sense, that it's hard not to give him a sort of pass.

On the other hand, I admit I can't let go of a certain nostalgia for the old dynastically-protected multiethnicity. There I am, for better or worse (probably, mostly, for worse). (In my own defense, if you want to read a 400-page study in self-dramatizing gits, try Dedijer's Road to Sarajevo.) That said, it's worth pointing out that the same society that so many elite Jews, including Stoppard's ancestors and Stefan Zweig and his family, thought was just The Best inspired Kafka to write The Trial, &c.

@David

That said, it's worth pointing out that the same society that so many elite Jews, including Stoppard's ancestors and Stefan Zweig and his family, thought was just The Best inspired Kafka to write The Trial, &c.

It's also the society that created Gavrilo Princip, The Black Hand, etc.

Also, it wasn't an "old dynastically-proteted multiethnicity", in so much as it was actually two fully distinct governments, with the Austrians and Germans running one half, and the Hungarians running the other, with entirely separate ministries and governmental offices except for the three matters of the military, finances, and diplomacy.

Moreover, while technically a "multiethnicity" in simple terms of demographics, it absolutely was a society in which the ruling minority ethnicities (Austrian, German, Hungarian) lorded over all the other ethnicities (Czechs, Poles, Ruthenians, Romanians, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Italians, etc) which actually comprised the majority of the population.

Austria-Hungary was largely held together by two major forces - overwhelming Germanic dominance of the military and the civil service; and a population of subject peoples who were each individually too small and uninfluential to enact change by themselves, yet who were too distrusting of each other to work together against their mutual oppressors for mutual benefit.

Wealthy Jews like Zweig managed to ingratiate themselves to the ruling elites, and so were able to achieve a level of wealth, privilege, and influence that the vast bulk of people living in the Empire could only dream of. And as already noted by John, people like Zweig seemingly took almost no notice of their fellow Jews who were NOT wealthy, and who were treated rather abysmally by the exact same ruling elites - a view which strikes me as both extremely short-sighted and extremely hypocritical.

I would go so far as to say that Zweig was probably a full blown Classist - more closely bound to the ruling elites by his family's wealth and the circles he moved within, than he was to his own religious and ethnic kin who languished in poverty and oppression.

I am, of course, fully aware of the structure of the Austro-Hungarian state(s) following the Ausgleich of 1867. I was referring to "dynastically-protected multiethnicity" more as an extremely broad type, taking in examples as various as the Sasanians, Abbasids, Alfonso X of Castle, the Polish-Lithuanian Union, and on and on.

Yes, as all of us have been saying all along in this discussion, Zweig's nostalgia is thoroughly shaped by his and his family's wealth, privilege, and connections (that's kind of what I meant by "an obviously out-of-touch elitist snot"). Beyond that, I am fully aware that none of the societies I mentioned was "tolerant" in any deeply-committed or reliable sense. I could go on with many, many arguments and pieces of evidence that I know go against my position. I was trying to present, simply, my personal stance, the sort deep inner stance one may have on an issue in a way that goes beyond evidence--the myths one loves, even when one knows they are myths, and even after many years of learning about how they're myths. That's what I meant by "for better or worse"--a phrase I use perhaps too much, but which I think I mean every time.

Post a Comment