However, this is actually hard to document, because maps made between 1865 and 1890 show very few people living in the area. Above is the location of Reno City shown on the 1874 Hopkins map, with only a few names listed, and we know that the Dovers were well-off white folks.

But the plan for Reno City already been hatched, as this 1870 plat shows. The school shown at the nearby intersection ("S.H.") was an African American school. So there were black folks living in the area. Plus, it seems unlikely that developers would have planned what became Reno City unless they knew there would be demand for the small houses and lots they envisaged for the property.

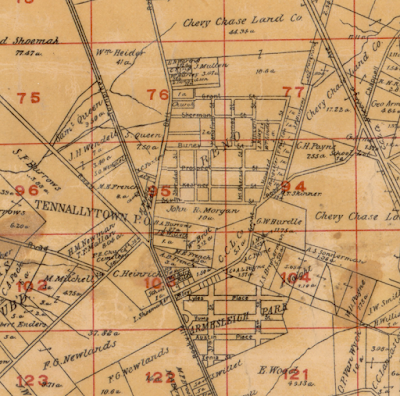

This 1891 map shows the street plan as it had developed by then. Maps do not show houses on most of the lots until later, though, so the neighborhood was built up gradually over time.

A detailed map from 1907 showing the houses that had been built by then, along with the reservoir that had been built within the old fort, using parts of the earthworks.

But even before the community reached its peak, forces began to gather bent on its destruction. In 1870 when Reno City was first imagined this was a rural area, the land not much valued. If you look back at the 1891 map you see that by then things were changing. A streetcar ran up Wisconsin Avenue from Georgetown, American University had been founded, and the vacant land in the area mostly belonged to developers like the Chevy Chase Land Company. Reno City, with its small frame houses on small lots (shown above in 1935), occupied mostly by African Americans, came to be seen as an obstacle blocking the development of northwest Washington, DC as an upscale community. Who wanted to live next to that riffraff?

So plans were set in motion to remove them. As this news story from the Evening Star of August 28, 1924 says, the DC surveyor had recommended condemning the whole place to make room for schools, an expanded reservoir, and a park. Because, he says,

In its present state the Reno subdivision is objectionable and a "blight" upon the locality because it is out of harmony with the highway plan and will preclude its development in an orderly and comprehensive manner.The result was a series of land grabs, as mapped here by a local historian. By 1951, everyone was gone.

You don't have to imagine that the DC surveyor was in the pay of the Chevy Chase Land Company; this problem is much deeper and more insidious than that. In the US local governments are still largely funded by property taxes, and at that time they were almost entirely funded by property taxes. This means that to have money for things like schools, roads, water, and sewers, communities need valuable property within their borders. Back then, and still today, poor people are usually a loss for communities, because they cost more in services than their land pays in taxes. Just a few years ago there was a move in Prince William County, Virginia, a DC suburb now much like Chevy Chase was in 1924, to ban the construction of townhouses because the residents of town houses cost the county too much money. Race was an additional factor in 1924 and still is today; one reason the existence of Reno City was blocking upscale development was that so many residents were black, and one reason many folks in PW County want to stop townhouses is that many who buy them are immigrants. But the basic arithmetic of taxes and spending drives city managers in that direction, and also provides a perfect cover for racism when one is needed.

It could be argued, and was, that the "sensible" thing for the city to do was to evict the residents of Reno City, promote the construction of wealthy neighborhoods round-about, and use the money to provide better services for poor folks in other parts of the city. Of course, the residents of Reno City did not see it that way. They protested, and by 1941 the NAACP protested with them. But to no avail; the stars of property speculation, the city's need for revenue, white power, and progress had aligned against them, and so they had to go.

No comments:

Post a Comment