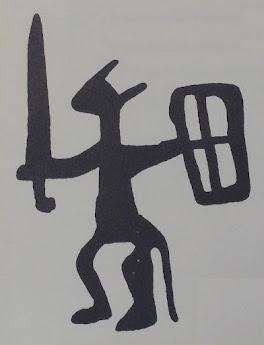

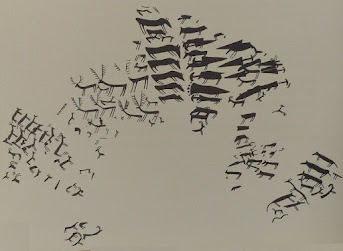

One of the puzzles of European rock art is the prominence of scenes widely seen as representing sun worship. Not that there is anything weird about sun worship, it's just that older European myth preserves essentially none of it. It is not prominent in Indo-European lore, nor was it a big deal among the Neolothic Anatolians who brought farming to Europe. (Think about Çatalhöyük, lots more bulls and vultures than sun symbols.) According to Anati, it dominates the earlier religious scenes at Camonica. A "horned god" figure emerges later, and toward the end of the series we see what looks like a warrior hero figure, perhaps like Hercules or one of the other semi-divine heroes so prominent in stories from the Iron Age. Anati notes that the largest gatherings depicted on the rocks are all scenes of religious worship; he calls this a procession.

This early scene is called The Wedding. Notice the very ancient Neolithic symbol of the bull's head at the far right, below the couple.

Later carvings depict a diversity of human acts. Including war, of course.But also craftwork. Here are two looms.Smiths at work; the lower one appears to be wearing a headdress like those shown on many priests. This may be a literal hat or may be a sign that something divine or magical is taking place.

Constructing a wagon.Several labyrinths of the Troy Town type are known. Notice that this one appears to have a face in the center.Anati thinks this represents a being, shown more fully on this example, which he connects to the myth of the Minotaur.

My favorite images are the ones that show houses. It's hard to know exactly how to interpret these but they are certainly wood frame structures with multiple stories, with stairs or ladders to the upper levels. There are also drawings that seem to be schematic representations of small towns, with scratches that may represent property lines or the layout of fields.These carvings are a wonder, an extraordinary window into the ancient past, and Anati's book is a treasure house for anyone who finds them fascinating.

Later carvings depict a diversity of human acts. Including war, of course.But also craftwork. Here are two looms.Smiths at work; the lower one appears to be wearing a headdress like those shown on many priests. This may be a literal hat or may be a sign that something divine or magical is taking place.

Constructing a wagon.Several labyrinths of the Troy Town type are known. Notice that this one appears to have a face in the center.Anati thinks this represents a being, shown more fully on this example, which he connects to the myth of the Minotaur.

My favorite images are the ones that show houses. It's hard to know exactly how to interpret these but they are certainly wood frame structures with multiple stories, with stairs or ladders to the upper levels. There are also drawings that seem to be schematic representations of small towns, with scratches that may represent property lines or the layout of fields.These carvings are a wonder, an extraordinary window into the ancient past, and Anati's book is a treasure house for anyone who finds them fascinating.

Wonderful rock carvings, but I'm distracted with pleasure at your story of finding the book. That's just the sort of thing one wants out of a giant warehouse of used books.

ReplyDelete