That nation turned out to be Sumer. As one of the claimants to the title of "first civilization," Sumer has been intensely studied for 150 years now. But we keep learning more about it, thanks to ongoing archaeology and the steady stream of new clay tablets coming from Iraq and Syria; the Second Gulf War and the collapse of the Iraqi state lead to a surge of looting and a parade of new tablets coming onto the world antiquities market, half of them bought by the Hobby Lobby people. And the more we learn about ancient Sumer, the weirder it seems.

Which brings me to a question that has been much in the culture lately: was civilization all a big mistake? Various recent writers (Yuval Levin, David Wengrow and David Graeber, etc.) have argued that civilization was an utter disaster and we should have stuck to equality and freedom. Or, at least, we should have maintained the option of equality and freedom, allowing people to pass back and forth between the two ways of living as some seem to have done in the past. This way of seeing the course of our history, along with the new archaeological findings, leads me to revisit Sumer and ask what it was all about.

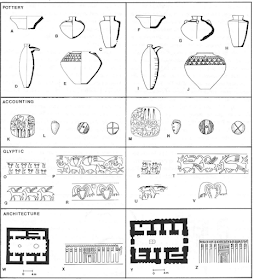

The place Sumerians identified as their first great city, Uruk, seems to have made the transition from big village to city between 4000 and 3500 BC. It was at Uruk that the Sumerians developed their writing system, transitioning from clay counters in different shapes to marks on clay tablets that represented the counters to pictographs for nouns to the recording of speech. The world we enter through the oldest tablets is both recognizable and bizarre.The tablets describe the arrangements of large agricultural fields, most of them owned by the En – usually rendered King or Priest-King – and the rest by other senior figures. The people who worked in these fields were provided with housing and rations of bread, beer, and cloth that came from centralized warehouses where the produce of the whole economy was stored. Taken literally, they seem to describe a communist society with at best a weak notion of private property, in which everyone worked for the bosses in return for a government house and a salary paid in food and drink, the techno-communist's fantasy of the "resource-based economy." The most common artifact from the residential districts at Uruk is the infamous Uruk bowl (above), made from a ceramic archaeologists usually describe as "shit" and molded with zero aesthetic care into a vessel of a standardized size, probably equivalent to one ration of grain or beer. Now it should be said that this system did not encompass the whole economy. Archaeology reveals a lot of stuff not mentioned in the distribution tablets, so there was more going on; likely private garden plots, side jobs, and so on. But so far as we can tell the main staples of life were really distributed in this regimented way.When they weren't laboring in the bosses' fields, ancient Sumerians seem to have spent a lot of time working on public building projects. Around 3500 BC the people of Uruk built the White Temple (digital reconstruction above), a fascinating building. After a foundation deposit had been laid down that contained the bodies of a lion and a leopard, work began. The excavators estimated that it would have taken 1500 workers, laboring 10 hours a day, about five years to build this one structure, at a time when the population of Uruk was likely around 30,000. When you add in the city walls, all the other temples, the palaces, the sewers, the major canals, etc., it seems like a very substantial portion of Uruk's available labor was spent on public works. I already mentioned here the calculations that show roughly 20 percent of all the available male labor in Old Kingdom Egypt went into building the great pyramids, and the figure for Uruk must have been similar.Living in mud-brick houses – some examples are above, with an open courtyard in the center and rooms on either side – subsisting mainly on bread and beer, laboring long hours in the fields or on building projects; why did people do it? This was a world, remember, where this was the only such city-state, surrounded by places where traditional village life went on unmolested. Nobody had to stay in Uruk.

.jpg)

-_Ausgrabungen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-03-112.jpg)

_decorating_the_walls_of_a_temple_at_the_city_of_Warka_(Uruk),_Iraq._2nd_half_of_the_4th_millennium_BCE._Vorderasiatisches_Museum.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment