For years in the 1970s Johns did almost nothing but these crosshatches, with the aim of creating images that were memorable but would defy the sort of Freudian interpretation people had used with Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock; that would be, so far as possible, absolutely meaningless. (My sister finds these paintings "hilarious." Puzzling, these professors.)

But in the 1980s when the AIDS crisis hit Johns felt that he needed a completely new approach to art to express his reaction to the unfolding holocaust of the New York gay community. He turned to the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944), bringing elements from Munch's works into his paintings and even reusing some of Munch's titles. So, ok, fine, it's interesting that when he needed inspiration even one of the most iconoclastic 20th-century painters turned to art history. And the exhibit conveys that behind 20th-century art was a whole lot of intellectual ferment. But if you don't like the art, what's the point? And basically I just don't like Jasper Johns. Like, he painted about fifty images of this same can with the brushes arranged exactly the same way. And no, it doesn't mean anything, on purpose.

(Actually I liked one Johns work in the show, this one: Hatteras, 1963. The arm that seems like the hand of a clock represents the arm of a sailor who drowned in a famous wreck, of whom nothing was seen but his arm reaching out of the water. But mostly it was crosshatching and coffee cans.)

What I liked about the show was the chance to see lots of stuff by Edvard Munch, most of which I had never seen before. Be honest, what of Munch's have you seen, other than The Scream?

I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence ... shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature.Portrait of Hans Jaeger, 1889,

The Sun, 1895.

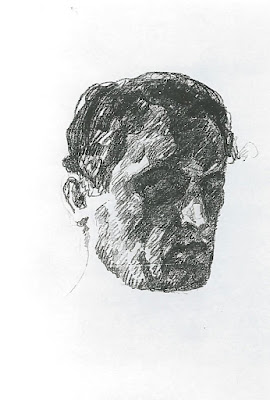

Self-portrait (1895 – note the severed arm, one of the motifs Johns copied)

Self-portrait in Shadow, 1912.

The Sick Child, one of many different versions of this image. It's dark, yes, but what did you expect? My favorite Munch is the one at the top of the post, Madonna, which I find hits a sweet spot between creepy and pretty.

Vampire, 1893.

And Starry Night, 1922-24.

Johns is fascinating in that he seems to have grown up poor and unhappy in a culturally sterile rural environment, and presumably that is part of what drove him toward wanting to become a famous and successful artist, once he moved to New York City and discovered his homosexuality.

ReplyDeleteOf course, the irony is that for whatever reason, he chose to embrace Dadaism of all things. When you're part of an art philosophy that attempts to opt out of critical appraisal by preemptively declaring your work pointless, you're going to have a hard time becoming a famous and successful artist.

But he had the good fortune to have been in New York City in a time when that sort of work was oddly well received, and he happened to develop relationships with individuals who were an influential part of the art scene.

I get the strong sense that he was less anamored with art, and more enamored with New York art culture. He seemingly didn't have anything insightful or impactful to say - hence the purposefully absurdity of dadaism - but he enjoyed the company of other artists and the lifestyle they led, and so if he's moving in those circles anyway, why not make and sell his own art, however absurd it may be?

He weirdly reminds me of Bob Ross: an ex-military man from the rural South who didn't find much satisfaction in what life offered him, who broke into art through his personal relationships, whose art was neither technically impressive nor particularly inspired, but whose works were curiously marketable as commercial pop art and allowed him to live a radically more cosmopolitan lifestyle than he otherwise could have.

The major difference between the two is that I actually like Ross' art and philosophy. If your work is nothing particularly special, doesn't have anything much to say, and is ultimately just a commercial product, then the least you can do with it is use it to encourage people to find joy and happiness through it.

I'd much rather spend half an hour watching ol' Bob leisuring painting trees and squirrels and talking about self empowerment and the value and ease of personal creativity, than spend that same half hour in an art museum looking at 50 identical paintings of brushes in a coffee can that say absolutely nothing whatsoever.

Well, you can do that. Some of his episodes -- if that's the right word-- from his Public TV show "The Joy of Painting" can be found on YouTube. Here is a shorty:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAyVuyJPP5k

Here's a complete show

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uEUMVwc4o5U

He had this soothing voice, and, boy, could he make it look easy (and fast).