Illustration from a 1560 copy of Khalīfah ibn Abī al-Maḥāsin al-Ḥalabī's The Sufficient Book on Ophthalmology, originally written between 1256 and 1275. This image shows much anatomical detail in the eye, but the brain is also shown schematically, by function.

From a manuscript dated 1347 illustrating Ibn Sina (Avicenna), De generatione embryonis. The cerebral ventricles are labeled "sensus communis" "fantasia", "ymaginativa" and "cogitativa seu estimativa." At the back of the head, the ventricle "memorativa" is labeled. The three compartments of the brain are labeled "cellula" 1, 2 and 3. Behind the eye is visus (vision); below that are olfactus, gustus, and tactus. In front of the throat is written: "Ducantur omnes lineae post angulum oculi, sed non ante versus nasum." This and the figure below are from Sudhoff, W. (1913) Die Lehre von den Hirnventrikeln in textlicher und graphischer Tradition des Altertums und Mittelalters. Archiv Fur Geschichte der Medizin VII, 149-205.

From a French manuscript dated 1400. The four compartments are labeled from the top: sensus communis, cellula imaginativa, cellula aestimativa rationis, cellula memorativa.

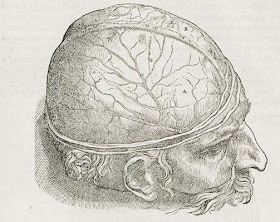

Diagram by Gregor Reisch, published in 1503, showing the functions of the mind divided among the three ventricles of the brain. This image was reproduced many times in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Drawing from Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks showing the rete mirabilis, a non-existent organ rather important in the history of science. Galen discovered this feature of some animal brains by dissecting monkeys, and he hypothesized that the human brain should have the same feature. It does not. So whenever you see a drawing of a human brain showing this feature (or the two-lobed liver), you know your artist is working from Galen rather than direct observation of the human body. So this drawing of Leonardo's is perfectly medieval.

Andreas Vesalius, from De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, 1543. These are the oldest images I know of that attempt to depict an actual physical brain. Vesalius was one of the real scientific heroes of the Renaissance, along with Galileo; he did not completely escape from the tyranny of Galen's text, but he got closer to real human anatomy than anyone before him. Based on my recent searches, it seems that in our fallen age the lower image is a common tattoo.

Thomas Willis and Christopher Wren, from Cerebri Anatome, 1664. Isabelle Moffat:

Standards are especially conspicuous when they shift dramatically, as they did following the 1664 publication of Thomas Willis’s Cerebri Anatome, illustrated by the famed architect (and astronomer) Christopher Wren. Willis removed the brain from the skull and studied it in the round, especially from below, then sliced through the organ to reveal its inner structures. He hypothesized that the brain stem was more important than the ventricles—which had recently been discovered to contain fluid, making them unlikely to house the mind—and so Wren’s drawings afford uncommon views of the base of the brain.Wren's drawings were better than Vesalius' partly because he and Willis figured out how to preserve the brain by injecting it with alcohol, allowing for a more leisurely study. This brings us to the modern era of anatomical study, which we will leave to people better versed in such things.

No comments:

Post a Comment